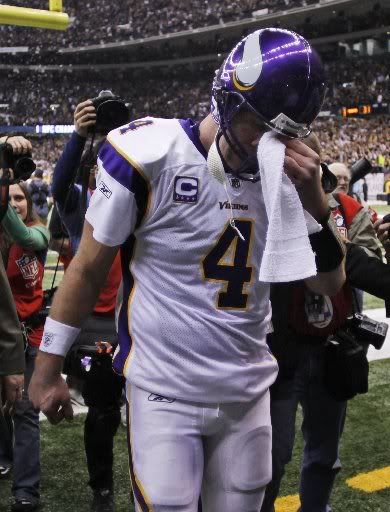

The NFC Championship game is over and Brett Favre and his latest potentially former employer, the Minnesota Vikings, have been left on the side of the road to the Super Bowl. That must mean it's time for Favre to begin his yearly kabuki dance to the tune of the Clash's "Should I Stay or Should I Go?"

The NFC Championship game is over and Brett Favre and his latest potentially former employer, the Minnesota Vikings, have been left on the side of the road to the Super Bowl. That must mean it's time for Favre to begin his yearly kabuki dance to the tune of the Clash's "Should I Stay or Should I Go?"

As this ritual plays out each late winter/early spring, the radio inside Favre's head must be on an endless loop of Mick Jones singing "If I go there will be trouble and if I stay it will be double." Meanwhile the fans of the Vikings, this time, will be holding their collective breath to see if Jesus-in-shoulder-pads will walk across the Great Lakes and back into their open arms.

Favre's inability to know when to say when isn't unusual when it comes to professional athletes. To localize the story a bit, Jim Thome just signed a 1-year contract with the Minnesota Twins, putting him two teams short of completing the rounds within the American League Central.

Perhaps Thome signed with the Twins because he thought that the state of Minnesota and the Twin Cities possessed magical powers of rejuvenation as Favre enjoyed an excellent regular season all while complaining about every ache and pain in his aging body. Maybe instead this is Thome's last stop on a very long career.

In one sense, it seems a bit sad and a bit pathetic to see once great athletes continue to hang on because they seemingly have nothing else to move on to. It's also a little exasperating to watch Favre play the role of drama queen each off season. But to be fair we do live in a capitalist society and it's hard to begrudge anyone doing what he can to make a buck. If the owner of the Twins or the Vikings is willing to dole out millions, how are they the bad guys for being willing to take it?

The short answer is that they're not.Let's face it, the life of a professional athlete at the tope level is far more peaches than beans, to quote noted sage Archie Bunker. The salaries make no sense in the context of most everyone else's daily life. It's a great, if limited, existence. The song that really should play in their heads is "Money for Nothing." And if you scour sites life Deadspin on a regular basis, you also learn that for most of them, the chicks are free, too.

And yet both fans and athletes continue to struggle with the question of when enough is enough. It's one of sports' great rhetorical questions.

Everyone has their own view on this, of course, and it really is athlete specific. Jim Brown and Barry Sanders, for example, walked away with still plenty left in the tank. As they did so, they left many fans in their wake aching for more. Johnny Unitas looked positively ridiculous riding the bench in San Diego for one miserable season at age 40. For that matter, Joe Montana looked ridiculous in Kansas City.

It's not just the big names, either. Did anyone really want to see Jamal Lewis back with the Browns this past season? But there he was anyway unable to walk away on his own. In truth he was brought back only because head coach Eric Mangini didn't feel like there was any other option. Mangini looked at Jerome Harrison and saw a part time back. He also looked at the rest of the roster and saw a bunch of untested rookies.

The plight of Lewis actually illustrates exactly why this issue is such a struggle for everyone involved. When Mangini bit hard and brought Lewis back he didn't then want to disrespect him by having him stand on the sidelines. As a result he stubbornly trotted Lewis out there game after game, to the exclusion of Harrison mostly, even though it was obvious that Lewis was done.

Indeed, if not for Lewis' injury, Harrison likely would never have had what turned out to be a break out season. It's also fair to say that the Browns' late season win streak, which occurred despite and not because of the quarterback play, doesn't happen unless Lewis gets hurt. So in a sense, Lewis ended up repaying Mangini's early season faith by actually getting injured. It probably is the single biggest factor in what saved Mangini's job.

This kind of situation plays itself out over and over again in city after city, sport after sport. Favre is a Hall of Fame caliber quarterback. But each year he comes back is another year in which the player behind him has a lost season of development. It's actually why Green Bay forced Favre's hand. They were tired of promising young quarterbacks that the team would soon be theirs as it became more and more obvious that Favre apparently had no intention of ever retiring.

For the Packers, it's worked out well. While Favre has been bouncing around the country, Aaron Rodgers has developed into a pretty fair quarterback who still has a decent upside. It's likely Rodgers wouldn't even be in Green Bay at all if the Packers management had decided to accede to each of Favre's demands.

The Twins signed Thome not only because he can still hit the long ball occasionally but also for the so-called "veteran leadership" position. It's really the same role Mark Grudzielanek will play for the Indians this season. I suppose it's an important role, but it's also a roster spot that won't go to a younger player.

It's not even that the Twins or the Indians won't get some level of production out of Thome or Grudzielanek. They will. But at what cost? For the Twins, the cost might be far less than the Indians. They are closer to the playoffs than the Indians and someone like Thome could put them over the top. Is that worth a lost season to a promising rookie? Most would say "yes."

But for the Indians, the answer is more complex. It's hard to calculate what a year of development at the big league level really means, but it obviously means something. How would the Indians have known the value of Grady Sizemore had they kept in buried in the minors in favor of somebody who used to be someone who now was just hanging by the bottom rung?

The other side of that argument, or at least the one Eric Wedge always used to put forth, is that you'd rather see that promising rookie play regularly at AAA than occasionally at the big league level. It's an argument of convenience.

In the case of Wedge, he much preferred the Grudzielaneks of the world anyway. But being a major leaguer is much more than just playing on the field. It's the bigger crowds, the increased travel. It's one adjustment after another and stunting that part of a player's development isn't healthy, either.

In truth, there isn't a professional athlete alive that ever completely solved this internal struggle just as there isn't a team that's found the right balance. The guess is that Brown and Sanders had moments in the few years after their retirement where they thought they left too soon. And as Favre was picking himself up off the ground last week in New Orleans it had to occur to him that he may be getting a little to old for this stuff.

The irony, of course, is that when they do retire, as they must, then end up in much the same place as other retirees, playing golf. And of all the sports out there, only professional golf has figured out how to solve the problem. It created the perfect way for players to gracefully put themselves out to pasture. It's called the Champions Tour.