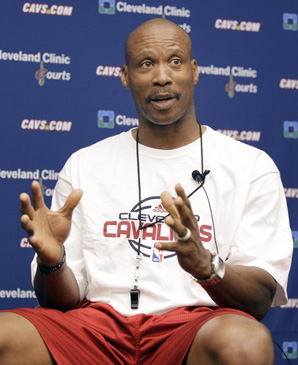

Byron Scott’s coaching record in three Cavs season was 64-166 – a .278 winning percentage. It is the worst winning percentage for any Cavs coach who patrolled the sideline for at least one full season.

Byron Scott’s coaching record in three Cavs season was 64-166 – a .278 winning percentage. It is the worst winning percentage for any Cavs coach who patrolled the sideline for at least one full season.

It’s worse than Bill Fitch (.412), who presided over a half-decade of expansion-era futility in early ‘70s, before the Miracle of Richfield gave the franchise its first taste of respectability. It’s worse that Bill Musselman, a Ted Stepien hire (.287).

It’s worse than Randy Wittman (.378), John Lucas (.298) or Paul Silas (.473).

The NBA is a business driven by wins and losses, and if you’re a coach who has too much of the latter and not enough of the former, you’re not going to hang onto your job.

That’s the simplest explanation for why Scott was fired on Thursday.

Even though the Cavs were most definitely in a rebuilding mode, where talent acquisition and player development takes precedence over winning for winning’s sake, wins still equal progress. If a young team wins games, it means the players are doing enough right to get leads and hang onto them until the final buzzer.

Scott’s teams raced out to leads, but repeatedly fell apart in the fourth quarter – most infamously after holding a 27-point second-half lead against Miami in late March, a loss that certainly rubbed the fan base the wrong way, and probably didn’t win Scott any additional support in the Cavs inner sanctum.

Way too often, the Cavs were caught with a collective deer-in-headlights stare when the time came to prove their mettle and put a game in the win column. And if you peel back the onion layers on Scott’s tenure, that’s the real reason why the Cavs will be searching for a new coach this spring.

It’s three years post-LeBron, and the Cavs are still searching for an on-court identity. Scott tried to install some form of the Princeton ball-motion offense, but too often, Kyrie Irving and Dion Waiters were left to freelance. Tristan Thompson seldom, if ever, had plays run through him. The center position was an offensive black hole once Anderson Varejao was lost for the season.

Scott tolerated random barrages of three-point chucking, even when the shots weren’t falling. Big men seldom tried to establish position on the left block. In short, the playbook might have had plays worth running, but the offense lacked a rudder.

But the offensive woes were nothing when compared to the utter lack of defensive presence Scott’s teams exhibited. Even when Varejao was healthy and snagging 15-20 rebounds a game, the team defense was shoddy. The Cavs defended the paint with nary more than a swinging saloon door. Kyrie received ample flack for his lack of defensive instincts, but his problems were symptomatic of a larger condition. Perimeter players frequently used poor judgment, gambling on steals in passing lanes, playing off their man for fear of getting burned, but leaving way too much operating space in the process.

The defense was quite simply a fundamental train wreck. And it was getting worse, not better.

Mike Brown (who ironically might emerge as a candidate), understood the basic concept of defense creating a product that is better than the sum of its parts. A team with overall mediocre talent can win games, make the playoffs, and even advance deep into the postseason, if they play great team defense. If you need any evidence, I present to you the 2007 Eastern Conference champion Cavs, with a starting lineup of LeBron James, Larry Hughes, Sasha Pavlovic, Drew Gooden and Zydrunas Ilgauskas.

Yes, that team got to the NBA Finals on the coattails of an epic Game 5 performance in the conference finals by LeBron, and Bucky Dent-esque performance from Daniel Gibson in the Game 6 clincher, but that team, with those players, won 50 games and three playoff rounds because they played defense at a high level. That was not a 50-win roster, let alone a conference championship roster.

You want the quickest way to return the Cavs to respectability? It’s probably by stopping the other team from putting the ball in the basket. And it’s something that Scott’s team simply wasn’t doing.

Everyone in the Cavs front office knows it. If Dan Gilbert’s statement to the media on Thursday is any indication, the next Cavs coach will be a defensive stickler:

“It has been our strong and stated belief that when our team once again returns to competing at the NBA's highest levels it will be because we have achieved our goals on the defensive side of the court.”

Of course, this isn’t all on Scott. Young teams are highly inconsistent and frequently stumble backwards as often as they stride forward. Compound that with injuries, which relentlessly assailed the Cavs over the past three years, and Scott wasn’t put in the best position to succeed.

But the basketball truism says defense travels with the team. So does a well-orchestrated offense. The backups play the starters in practice every day, so the guys coming off the bench are as grounded in the system as the guys who run onto the floor amid smoke and pyrotechnics during the opening introductions.

Maybe Scott was burned out by coaching the team through loss after loss. Maybe there was friction in the locker room. Maybe Scott’s personality is more tailored for coaching a self-starting veteran team instead of a young team that needs constant maintenance. Whatever the reason, if he had a grand vision for what the Cavs could become, it was never realized. It never really hatched out of the egg, for that matter.

The Cavs now embark on an extremely important offseason. They need to find a coach who can reach this team’s collection of impressionable young players and put them on a path to becoming a well-oiled offensive – and especially defensive – machine.

They need to add more talent, and not all of it straight from the draft. There isn’t much value in making this team even younger. GM Chris Grant probably needs to orchestrate at least one major veteran acquisition this summer.

When the Cavs take the floor with their new coach and their tuned-up roster next fall, they need to be a playoff team from the first game – and a fairly strong playoff team at that. At this stage, after three years of putrid basketball, squeaking in as the eighth seed on the last day of the season doesn’t cut it. The Cavs need to become an above-.500-and-rising team, capable of competing for a middle seed, and maybe even make some noise in the race for homecourt advantage in the first round.

And to do that, they need an identity. Dan and Chris, it’s your move.