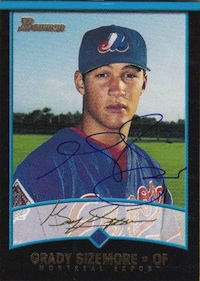

The golden boy. The face of the franchise. In Cleveland, even this sort of idyllic archetype is really just a sitting duck—susceptible to a miserable fate somewhere between the extremes of "burning out" and "fading away." At just 31, Grady Sizemore finds himself in that wicked limbo; his career as a Cleveland Indian over, and his baseball future shrouded in doubt. The road from budding superstardom to career retrospectives shouldn’t be this short. But we’ve seen it all before.

The golden boy. The face of the franchise. In Cleveland, even this sort of idyllic archetype is really just a sitting duck—susceptible to a miserable fate somewhere between the extremes of "burning out" and "fading away." At just 31, Grady Sizemore finds himself in that wicked limbo; his career as a Cleveland Indian over, and his baseball future shrouded in doubt. The road from budding superstardom to career retrospectives shouldn’t be this short. But we’ve seen it all before.

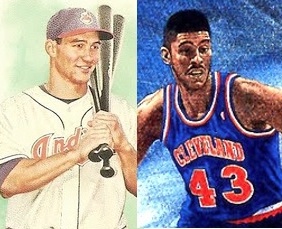

The Center and the Center Fielder

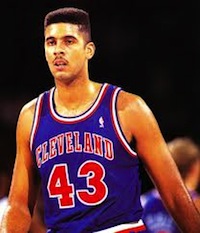

Grady Sizemore and former Cavaliers big man Brad Daugherty both made their pro debuts at the age of 21 and played their final games (at least for now in Sizemore’s case) at 28. That’s eight seasons a piece in a Cleveland uniform—following remarkably similar career trajectories that carried the eventual fates of their respective franchises right along with them.

Of course, it wasn’t Father Time, or “diminishing skills,” or any easily identifiable on-field tragedy that pushed these popular stars out of the limelight. It was the slow, gradual betrayal of their own bodies—the same muscle and bone that they’d each spent their lives crafting into machines of their trade. Once the pictures of durability, Sizemore and Daugherty wound up as Cleveland’s unlikely poster children for how fleeting athletic success can be—and how damaging the loss of a central star can prove for a team.

The Bright Beginnings

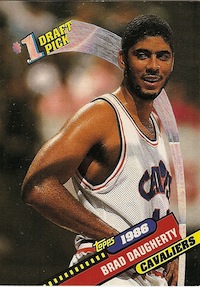

For his part, Daugherty certainly came to town with the higher expectations of the two. While Sizemore was a former third round pick and a toss-in of sorts in the unpopular 2002 trade of Bartolo Colon to Montreal, Daugherty garnered instant name recognition when he became not just the Cavs’ first pick in the 1986 NBA Draft, but the #1 selection over all. He was a legit, broad-shouldered 7-footer, and his feathery touch and wide array of post moves came with the UNC/Dean Smith stamp of approval. For a Cavs team that had gone just 29-53 a year earlier, Brad was now “The Man.”

As it happens, this was the same miraculous draft in which Cleveland also added future all-stars Ron Harper and Mark Price. Nonetheless, it was well understood that Daugherty would be the instant difference maker and the focal point of any future playoff runs the team hoped to enjoy. And true to form, he didn’t disappoint. The Cavs improved to 31 wins in 1986/87, then 42 wins in 87/88, with Daugherty averaging 16 and 19 points per game, respectively. By age 22, he was already an All-Star and widely regarded as one of the elite centers in the league.

At the exact same age, Grady Sizemore rapidly entered similar conversations about his sport’s finest young center fielders. After a cup of coffee with the Tribe in 2004, Sizemore took over center for good in 2005, and as no coincidence, the rebuilding Indians started turning the corner, as well. Appearing in 158 games, Grady hit .289, cracked 22 homers, drove in 81, and stole 22 bases. The Indians won 93 games, narrowly missing the postseason.

If Daugherty had Price, Harper, and Hot Rod Williams to grow with, Sizemore seemed to have some impressive young running mates of his own in Victor Martinez, CC Sabathia, and Travis Hafner. The sky was legitimately the limit.

Peak of Their Powers

The Cavaliers finally put it all together in the 1988/1989 season, winning a then franchise-record 57 games. Daugherty again was the model of consistency, appearing in at least 78 games for the third straight year, and averaging 19 points and 9 rebounds. Unfortunately, Michael Jordan’s now eponymous “Shot” cut Cleveland’s postseason short. And a year later—at just 24—Daugherty found himself on the injured list for the first time. All told, the Cavs’ postman missed 41 games in the ‘89/’90 season recovering from nagging back problems. To his credit, though, it once seemed like nothing more than a brief setback.

Over the next three years, Brad played through the pain and actually took his game to another level, appearing in at least 70 games each season while averaging 21 points and 10 boards. The high point was 1992, when Daugherty—fresh off another All-Star season—helped lead the Cavs all the way to the Eastern Conference Finals. Again, Brad's former North Carolina teammate Michael Jordan was there to ruin the party, as he would a year later, as well. But at just 27, Daugherty still had plenty of reasons for optimism. Word was His Airness was leaving the Bulls to play baseball, opening the door for the Cavaliers to finally take their next step. Daugherty had his opportunity... and time on his side.

As for Sizemore, it’s easier to forget now, but from 2006 to 2008, he wasn’t just considered one of the top center fielders in the game. To many, he ranked among a handful of the best players in the league, at any position. Equally popular with Peter Gammons and your girlfriend, Sizemore didn’t miss a single game in 2006 or 2007, and only sat out five in 2008. He made the All-Star team all three seasons, and added a pair of Gold Glove awards to his mantle for good measure. His unique combination of power and speed was also drawing him some scary historical comparisons.

As for Sizemore, it’s easier to forget now, but from 2006 to 2008, he wasn’t just considered one of the top center fielders in the game. To many, he ranked among a handful of the best players in the league, at any position. Equally popular with Peter Gammons and your girlfriend, Sizemore didn’t miss a single game in 2006 or 2007, and only sat out five in 2008. He made the All-Star team all three seasons, and added a pair of Gold Glove awards to his mantle for good measure. His unique combination of power and speed was also drawing him some scary historical comparisons.

Based on numbers put up through the age of 25, Sizemore’s closest statistical equivalents—according to baseballreference.com-- included Carlos Beltran, Jack Clark, Andre Dawson, and a couple fellas named Duke Snider and Barry Bonds. It was no exaggeration whatsoever to say that Grady Sizemore had Hall of Fame caliber talent.

By 2007, his ballclub had some pretty historically significant potential of their own. Carrying over the momentum from a 24 homer, 33 SB season, Sizemore hit .375 against the Yankees in the Division Series, leading the Indians into the ALCS. Things went shockingly south against Boston in that series, of course, but as a rising star still in his mid 20s, Sizemore had to feel confident he’d have many more playoff at-bats ahead of him.

Shelf Life and Life On the Shelf

The word “injury” actually comes from the Latin “injuria,” which—along with meaning “hurt”—also means “wrong,” “unjust,” and “insult.” Probably safe to say that Sizemore and Daugherty wouldn’t argue with any of those readings. Before their numerous battle scars robbed them of their promise, each man was the centerpiece of two clubs on the rise—the Cavs of the early ‘90s and the Indians of the middle 2000s.

In their first three full seasons, neither Sizemore nor Daugherty spent any time on the disabled/injured list. By the age of 27, they were almost exclusively in street clothes.

On February 23, 1994, Brad Daugherty took a seat after scoring 8 points in 11 minutes of action against the Washington Bullets. His ever fragile back was acting up again. At first, he was day to day. Then he wound up sitting out the remainder of the 93/94 season.

Still just 28 years old, Daugherty did the only sensible thing—he rehabbed, thoroughly believing he could come back as he had several years earlier. As time passed, however, it seemed to Cavs fans that the updates on Daugherty’s condition came fewer and farther between. And as 1994 turned into 1995 and 1995 into 1996, it finally became clear that the long awaited return of #43 had become nothing but a pipe dream for the now rebuilding Cavaliers. After the 1995/96 season, Daugherty officially announced his retirement. Even in a career half as long as it could have been, he walked away as the Cavs’ all-time leading scorer and rebounder, only to be passed by LeBron James and Zydrunas Ilgauskas some 15 years later.

Unfortunately, Grady Sizemore didn’t get the chance to puncture the much lengthier Cleveland Indians record book quite as we all imagined he would. Like Daugherty, it was eventually severe back problems that hobbled his rehab efforts. But long before that disastrous final season as an Indian ($5-million contract, Zero games played in 2012), Sizemore had already become a shockingly injury prone animal. The former Tribe iron man played just 106 games in 2009 (groin injury, elbow surgery), then 33 in 2010 (left knee surgery), and 71 in 2011 (right knee and sports hernia surgery). In the latter campaign, he showed flashes of his old brilliance after coming off the disabled list in mid April. But an unlucky slide at second base put him right back on the DL yet again.

Unfortunately, Grady Sizemore didn’t get the chance to puncture the much lengthier Cleveland Indians record book quite as we all imagined he would. Like Daugherty, it was eventually severe back problems that hobbled his rehab efforts. But long before that disastrous final season as an Indian ($5-million contract, Zero games played in 2012), Sizemore had already become a shockingly injury prone animal. The former Tribe iron man played just 106 games in 2009 (groin injury, elbow surgery), then 33 in 2010 (left knee surgery), and 71 in 2011 (right knee and sports hernia surgery). In the latter campaign, he showed flashes of his old brilliance after coming off the disabled list in mid April. But an unlucky slide at second base put him right back on the DL yet again.

On September 22, 2011, Sizemore—back after two months on the shelf with the aforementioned knee injury—went 1-for-4 in an 11-2 Indians win over the White Sox at Progressive Field. He hasn’t played since.

Having recently announced that he still is working toward a return, odds are decent that Grady could get a minor league deal with someone in 2014. Even a Sizemore at 60% of his old self would be worth a look for plenty of teams. The lamentable fact, though, is that-- at his full power-- Grady was a potentially once-in-a-generation kind of player; Mike Trout before Mike Trout. Any Grady Sizemore that suits up for a team from here on out could only hope to be a shadow of the kid we came to know.

Aftershocks

In the same year Grady Sizemore’s consecutive games played streak ended, the Indians eventually held a firesale, closing the window on the title hopes of the Sabathia/V-Mart/Hafner era (an era that feels officially concluded now that Hafner and the former Fausto Carmona have also also mercifully moved on). It didn’t help that Travis Hafner’s own career has followed a similarly injury ravaged course. But all things considered, no departed player—not even Sabathia, Martinez, or Cliff Lee— proved to be a more damaging loss for the Tribe than a man they still actually had on the payroll up until this season: Grady Sizemore.

As for the Cavaliers, it would take more than a decade for the franchise to finally recover from the premature demise of the Daugherty squad, as another #1 overall pick arrived on the scene in 2003. Today, it’s widely agreed that LeBron James, at the age of 28, is just entering his prime. But at that same age, Brad Daugherty—and possibly Grady Sizemore—saw their primes become their swan songs. You just never know what’s gonna happen in sports, except that it ain’t always gonna be fair.