A young Amish boy smiled and waved from a horse-drawn trailer as it passed, an apropos welcome to the miniscule community of Peoli, Ohio. Like nearly everything else along Route 258, a country road that meanders through the rolling hills and green pastures of God’s country in Ohio, the Amish trailer and its friendly passengers are a reminder of how some parts of the United States remain unadulterated. A quarter mile to the south, cattle are grazing. For miles and miles to the north, trees stretch toward the horizon line. To the east, the prototypical hill in the countryside, with deep shades of green and a wayward mother cow and her calf. A car, almost always a truck, passes every five minutes or so. This place is serene. It’s picturesque. The air is clean. The breeze is cool and refreshing.

A young Amish boy smiled and waved from a horse-drawn trailer as it passed, an apropos welcome to the miniscule community of Peoli, Ohio. Like nearly everything else along Route 258, a country road that meanders through the rolling hills and green pastures of God’s country in Ohio, the Amish trailer and its friendly passengers are a reminder of how some parts of the United States remain unadulterated. A quarter mile to the south, cattle are grazing. For miles and miles to the north, trees stretch toward the horizon line. To the east, the prototypical hill in the countryside, with deep shades of green and a wayward mother cow and her calf. A car, almost always a truck, passes every five minutes or so. This place is serene. It’s picturesque. The air is clean. The breeze is cool and refreshing.

It’s here where one of the most famous and decorated baseball players in the history of the game is buried. Denton True “Cy” Young wouldn’t have had it any other way. Peoli, Ohio wouldn’t even count as a blip or a speck on a map, situated between Newcomerstown and Freeport in Tuscarawas County. Peoli Cemetery sits partially in the shadow of Peoli Church, a red brick building built circa 1870. About 10 buildings and this old church and cemetery make up the community of Peoli. Young seemed to always find his way home, in life and in death.

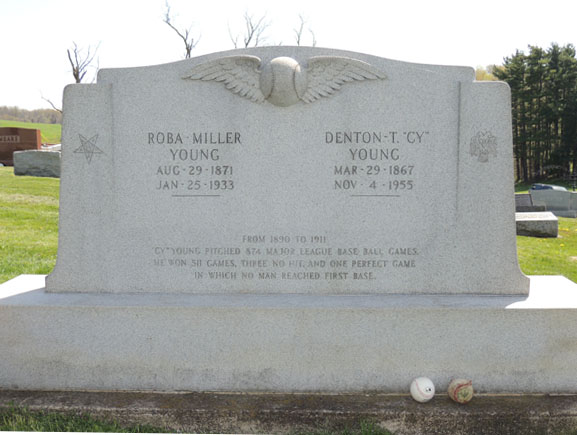

Young shares a headstone with his wife, Roba, and shares a cemetery with true, small town American heroes, including World War II sergeants, World War I veterans, and Civil War veterans. Generation after generation of family members are buried here together. The Beal family. The Roberts family. The Hollingsworth family. The Simmerman family.

In a way, it is unfathomable to think about Cy Young’s final resting place as being in a place that is completely devoid of fanfare. Two baseballs, a couple of pots of dead flowers, some silk flowers, and a tattered American flag attached to a marker for the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks were the only adornments at the site. One would think that, for a pitcher who holds the Major League record for wins, wins above replacement pitcher, complete games, and innings pitched, there would be more of a celebration of his life, even if he died nearly 60 years ago.

But, this is exactly the way Cy Young would want it. He retired to Peoli after his playing days because he wanted to return to his humble upbringing and the life he knew from growing up on a farm in nearby Gilmore, Ohio. He grew potatoes and tended livestock until his wife died in 1934. Filled with grief, Young sold his farm and tried to play exhibition baseball games in Georgia during the Great Depression to try to make ends meet. Ultimately, Young found his way back to rural Ohio to work in a retail store before dying in 1955.

But, this is exactly the way Cy Young would want it. He retired to Peoli after his playing days because he wanted to return to his humble upbringing and the life he knew from growing up on a farm in nearby Gilmore, Ohio. He grew potatoes and tended livestock until his wife died in 1934. Filled with grief, Young sold his farm and tried to play exhibition baseball games in Georgia during the Great Depression to try to make ends meet. Ultimately, Young found his way back to rural Ohio to work in a retail store before dying in 1955.

On a beautiful Saturday afternoon, children ran around carefree in their yards, in the same manner that adolescent Cy Young once did. It was on these pastures and on these fields that Young honed his baseball skills. He played on semi-pro teams in Newcomerstown and in nearby Cadiz, Carrollton, and Uhrichsville. He started a team in his hometown of Gilmore. His baseball career really began in 1890 when he played in the Tri-States League with Canton. A year later, Young had his first professional contract with the Cleveland Spiders of the National League.

Young was technically traded to the Spiders by the team in Canton. The cost? $300 and a suit for the owner of the Canton team. It was during that season with the Spiders that Young received his nickname of Cy, after going by Dent Young during his years in the semi-pro leagues. It was short for Cyclone, a reference to how fences looked like they had been destroyed by a cyclone when Cy threw at them. Noted baseball statistician Bill James wrote in his book, The New Bill James’ Historical Abstract, that Young’s catcher, Chief Zimmer, put a piece of beefsteak in his glove to soften the blow from Young’s fastball. Two years later, the pitcher’s mound was moved back to its current distance of 60 feet and six inches, in part, because of how fast Cy Young threw.

Young spent 22 years pitching in the Major Leagues for the Spiders, the St. Louis Perfectos and Cardinals, the Boston Americans, Red Sox, and Rustlers, and the Cleveland Naps. He threw one perfect game, two no hitters, and was 2-1 with a 1.85 ERA in the 1903 World Series for the Boston Americans. The Americans won the series 5-3, marking the only World Series championship for Young in his career. He led the league in wins five times.

At his final resting place, Young’s headstone doubles as his résumé. The inscription reads: “From 1890-1911 “Cy” Young pitched 874 Major League Base Ball games. He won 511 games, three no hit, and one perfect game in which no man reached first base.” A baseball with angel wings protrudes from the front-facing of the stone. Symbols of the Freemasons were also carved into the stone. Young had a Master Mason Degree, which he earned in 1904 from the Mystic Tie Lodge #194 in Dennison, Ohio.

At his final resting place, Young’s headstone doubles as his résumé. The inscription reads: “From 1890-1911 “Cy” Young pitched 874 Major League Base Ball games. He won 511 games, three no hit, and one perfect game in which no man reached first base.” A baseball with angel wings protrudes from the front-facing of the stone. Symbols of the Freemasons were also carved into the stone. Young had a Master Mason Degree, which he earned in 1904 from the Mystic Tie Lodge #194 in Dennison, Ohio.

Young and his wife had a daughter who died just hours after birth, leaving no surviving family members after Cy’s death. Young’s legacy lives on in the prestigious award that bears his name, given every season to the best pitcher in each league, and also in the bust and accompanying plaque of his accomplishments in Cooperstown, New York, the home of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In small towns all across our great land, we can find the achievements of the people that make up the backbone of America. We talk about the “American Dream” in the present day and overlook that Cy Young lived the “American Dream” in the late 1800s. He went from a farm boy in the fields of rural Ohio to the big cities of Cleveland, Boston, and St. Louis, his legacy forever immortalized in baseball’s record books. He became a role model for young boys everywhere, the ones restricted to playing baseball at the city park and the ones free to roam spacious tracts of land from dawn until dark hitting and pitching and fielding.

Among the weathered gravestones that can no longer be read in Peoli Cemetery is the final resting place of possibly the greatest pitcher to have ever lived. There are no historical markers. There is no big display. Just a farm boy buried amongst other farm boys and girls.

The cool wind blows again. It doesn’t feel anything like a cyclone.

(Pictures courtesy of Jennifer Pearce.)