JULIO!!!

JULIO!!!

Go ahead, say it. Shout it out loud, just like thousands of Cleveland Indians fans used to do, back in the day.

WHOOO LEEEEE OHHHHHHHH!!!!

Felt good, didn't it? If you followed the Tribe in the 1980s, and perhaps only as early as 1996/97, shouting Julio Franco's name is bringing back some fond memories of a local favorite.

And right now, you are smiling.

The Tribe had acquired Dominican Republic native Julio Franco as a second-year shortstop in a 1983 trade with the Philadelphia Phillies. At the time, the trade was billed as the Tribe's top prospect, Von Hayes, for 1982 Gold Glove second baseman Manny Trillo and lesser prospects.

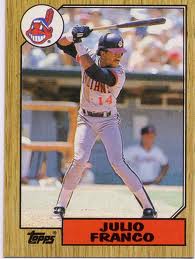

Franco was basically a stud hitter who batted over .300 with the Indians in every year from 1986 through 1989. This was in spite of his use of the heaviest bat allowed (reportedly 36" and 33 ounces), and his unconventional batting stance (if you have just shouted Julio's name, you might also have memories of pointing the bat over the top of your head at the pitcher while standing knock-kneed and sticking your butt out, imitating Franco). He was also a 30+/yr base stealer. However, his glove work and lack of range at shortstop were horrible at times, and he led the league in errors in 1984 and 1985. Franco's fielding was said to be the reason Philadelphia was willing to let him go. He did improve; some feel this was a result of his defense being used against him in salary arbitration hearings.

While with the Tribe, Julio Franco was variously viewed either as colorful or as a head case. When he first arrived in Cleveland, just off the plane, he reportedly wore no coat, had $5,000 stuffed into a sock, and was asking where the casinos were (Cleveland casinos? Huh, that'll never happe- uh, never mind). Beginning in 1983, Pat Corrales was his manager. Coincidentally, Corrales had also been his manager in Philadelphia the year before. Corrales later acknowledged that like many ballplayers, Franco enjoyed him some beer and women. He was described as ‘cocky' and ‘rash.' He was very talented, and he knew it. And yes, there were also some discipline issues. Once, in New York, Franco had come through with a game-winning hit. Celebrating his brother's birthday, he stayed out late afterwards, and didn't bother showing up for the next night's game (wonder if he used today's ballplayer's "flu-like symptoms" excuse?). Corrales routinely fined Franco for a lack of hustle, as well. It was matter-of-fact, without any hollering from Corrales. Franco would come off the field, walk by Corrales, and ask, "How much?" Corrales would calmly reply with the amount of the fine.

Another side of Franco's personality was evident when, once, he hit a line drive which struck a Detroit Tiger in the face, and Franco was seen stooped over and in tears while on first base.

During the early part of the 1985 season, Johnny LeMaster was acquired by the Tribe to play shortstop. Franco was asked to play second base. The player to be moved to the bench was his friend, Tony Bernazard. Franco protested the move, and LeMaster was traded away three weeks later. Franco remained at shortstop until 1988, when Bernazard was traded and Corrales was fired.

By the time the end of the 1980s arrived, the Tribe had suffered through a loooong era of losing. This included a painful withering under the white-hot national spotlight of high hopes in 1987. Some said Franco's effect on the team was divisive, while others felt he was an ‘easy target' on a terrible team. After the 1988 season, mild-mannered manager Doc Edwards gave the front office an ultimatum: he would not return in 1989 if Franco returned. Edwards reportedly had had enough of Franco's attitude and lifestyle, including his habit of bringing a Rottweiler and a snake to the Indians' clubhouse. (Sports Illustrated, August 13, 2007)

Latin players such as Franco had a widely-held reputation in the 1980s as uncooperative, arrogant head cases who acted out. Many players from Latino cultures are seen as extremely proud and sensitive, especially to insult. However, being looked to as a leader can sometimes transform such a player into a "model" teammate. (The Social Roles of Sport in Caribbean Societies, Michael A. Malec) Indeed, being traded to the Texas Rangers for the 1989 season seems to be an important turning point in Julio Franco's career. Some feel he was welcomed in Texas as a leader, and this was the beginning of his status as a true star: he was an All-Star three times for the Rangers and led the league in hitting in 1991 with a .341 average. Franco also assumed a role on the Rangers as one who counseled young players to keep their temper under control. Franco became a devout Christian during this time, as well. This was at the start of the George W. Bush era with the Rangers. Franco and ‘W' remain close friends today.

Julio Franco had one of the best years of his career in 1994. He hit .319 for the Chicago White Sox. Tribe fans will recall that year as being shortened due to owner/player bargaining issues. At that time, no one knew whether there would be a season in 1995; Franco wanted to play ball, so he signed with the Chiba Lotte Marines in Japan. He was with the Marines twice during his career. He played alongside American Pete Incaviglia, and under manager Bobby Valentine. Franco remains a favorite in Japan, and the feeling is mutual. In a 1996 interview , Franco gave his impressions of Japanese baseball:

- The tough Japanese-style workouts help a player's longevity.

- Japanese players were too hesitant to steal and take extra bases. They feared being thrown out. And they were too willing to bunt.

- The umpires often changed their strike zones during games.

Franco played with several other organizations in the following years, in the U.S., Japan and in Mexico. He was actually booed by Cleveland fans during a few return visits with other teams (envious of his success while the Tribe's efforts remained futile), but was again cheered as a hero when he was re-signed by the Indians in 1996 as a role player in that historically powerful lineup.

Should Julio Franco wind up in the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame? Let's consider. He had an impressive and storied career. He has the most hits among all Dominican-born players (the list includes Sammy Sosa, Pedro Guerrero, Rico Carty, the Alou brothers, George Bell, and eventual Hall of Famer Albert Pujols). When one totals his hits including those from his Japan and Mexico days, they add up to over 4200. But we can't do that in determining Hall eligibility, of course. He is a lifetime .300 hitter as a middle infielder/DH with 2,586 total major league hits. He was a three time All Star who finished as high as 8th in MVP voting. He led the league in batting once. He never starred in the postseason. His closest ‘comp' is Alan Trammell (their MLB numbers are very similar. Franco had the better average and Trammell had a little more pop). Trammell's defense was solid and steady. Alan Trammell is not in the Hall of Fame...

Franco's long-time career goal was to play until he was 50 years old. He became extremely health-conscious and was careful about what he ate. He also became a workout warrior. When he retired from baseball a few years ago while with a team in Mexico, Franco came up a little short of his goal, as he was ‘only' 49 years old. But wait- was he really born in 1958, the year everyone accepts? Early references to Franco's birth date vary. Dominicans' birth dates have sometimes been in question, so we really don't know for sure. It's just another facet of Franco's long and colorful career, which may remind readers of that of many stars from the old Negro leagues. Nicknamed "Moses" in 2006 by teammate Billy Wagner, he holds several age-related baseball records.

And he's remembered fondly from his days in Cleveland, where Julio Franco has said was the only stop throughout his decades of playing ball where the fans would shout his name.

Next week: We look back on the career of Tribe closer Doug Jones.