I hate being featured in other teams' highlights.

1) Skip, that horse looks awfully tall

After Friday's game, I lobbied for Fausto Carmona to have been

given (oy, what verb tense is that? Past plu-future imperfect

degenerate?) the opportunity to close out the game, arguing that we

needed to see if he was An Answer (there is rarely The Answer, and if

there is, you're in trouble) at Closer. My argument at the time was

that the situation was tailor-made, in that it was at home, against a

weak-hitting team, starting an inning with no one on, following a

dissimilar pitcher, but close enough to actually learn something. I

stand by this, because one of the dimensions of Decision Space is time:

evaluating a decision should be done in the context of the information

available and not with respect to what happens later.

Carmona did get into a tie game later that series, and he was

truly atrocious, but hey. It doesn't change my argument, and besides,

this is not a team for which one win is important in the standings.

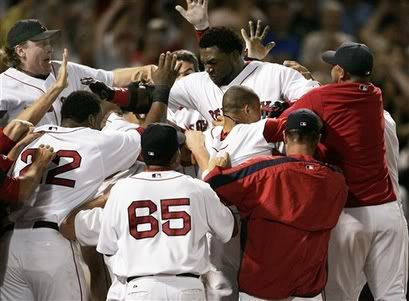

Instead Fausto Carmona's first Save Opportunity comes in Boston

... following two similar pitchers ... into the teeth of one of the

best offenses in major league baseball. Kudos for setting up a

challenge, but I claim that a save Friday would have done more to

prepare Carmona; heck, even a blower would have taught us something.

Now all we've learned is that Fausto Carmona can give up a home run to

David Ortiz, making him roughly one of nine thousand pitchers to do

so. Giving up a hit to Alex Cora is bad enough, but walking Youkilis

after 1-2 is truly execrable.

Look, here's my problem with Carmona: the obvious thing that a

closer must do is get people out. However, generally speaking, this

boils down to a couple key factors: the two most valuable elements of

this are missing bats and throwing strikes. This isn't terribly

different from any other successful pitcher, but it becomes magnified

for the closer who has no time to "make up" any mistakes. Wickman

didn't strike out a lot of guys, but he normally threw a lot of

strikes. Bobby Jenks threw with the accuracy of a shuttlecock last

season, but he struck out a million guys. You have to do one or the

other, and doing both is really good.