As expected, the Cleveland Indians have been mere apparitions at baseball’s winter meetings this year. The buzz: inaudible. The rumor mill: in foreclosure. But for fans bemoaning the boredom of another lukewarm hot stove, consider the opposite extreme exemplified a half century ago by the man known as “Trader Lane.” In the months before the 1960 season began, the trigger-happy Tribe GM made both the most astute and most shortsighted transactions of his infamous reign, and neither one involved Rocky Colavito.

As expected, the Cleveland Indians have been mere apparitions at baseball’s winter meetings this year. The buzz: inaudible. The rumor mill: in foreclosure. But for fans bemoaning the boredom of another lukewarm hot stove, consider the opposite extreme exemplified a half century ago by the man known as “Trader Lane.” In the months before the 1960 season began, the trigger-happy Tribe GM made both the most astute and most shortsighted transactions of his infamous reign, and neither one involved Rocky Colavito.

When Victor Martinez returns to Cleveland next season donning the gothic “D” of the Detroit Tigers, it's likely to dredge up some painful memories for Tribe fans who can still recall the spring of 1960. For many, April 17 is the day that lives in infamy. This was the essential moment in Indians folklore when notorious tinkerer Frank Lane shipped Colavito-- easily the best and most popular player on a team that had finished second in the AL pennant race in 1959— to the rival Tigers for batting champ Harvey Kuenn. Call it the start of a curse or just a mind-blowingly bad PR move; either way, it’s a story that’s already been told a thousand times. For the purposes of this tale, however, we'll be digging a bit deeper-- re-examing the other wheelings and dealings during an Indians off-season for the ages. How does a hot stove session devolve from a tune-up to a total overhaul? This is how.

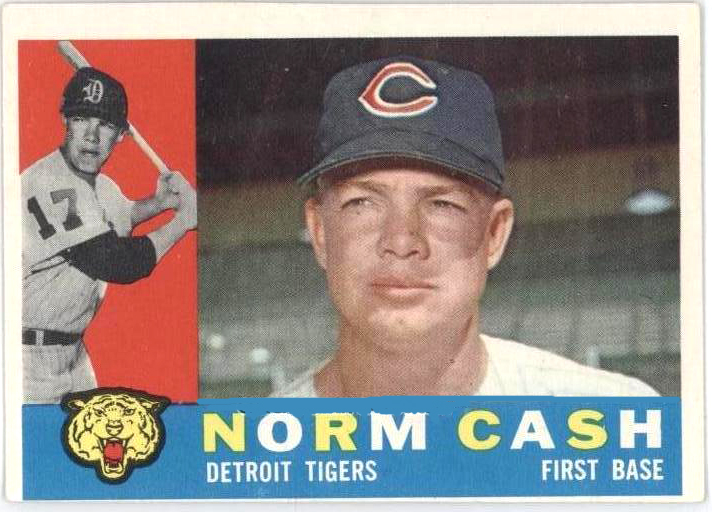

The Curse of Norm Cash: The Backdrop

The 1959 Indians were a team on the brink of greatness. Their 89-65 record had seen them finish just 5 games in back of Chicago, having bit at the Sox heels all summer long. Colavito (25 years old), outfielder Tito Francona (25), and power-hitting shortstop Woodie Held (27) were all entering their primes, and the pitching staff featured a number of youngsters with live arms—Herb Score (26), Gary Bell (22), Jim “Mudcat” Grant (23), and Jim Perry (23) among them. The roster also boasted a good balance of veteran leadership. Staff ace Cal McLish (33) had gone 19-8 in ‘59, and first baseman Vic Power (31), second baseman Billy Martin (31), and left fielder Minnie Minoso (33) were key cogs in an offense that led the league in batting average, homeruns, and runs scored.

The team was an obvious favorite to make a pennant run again in 1960, but Frank Lane wasn’t as convinced as everyone else seemed to be. Colavito was the casualty we all remember, but the almost-as-popular Herb Score was also shipped off the very next day-- to the White Sox, of all teams-- for pitcher Barry Latman. And that was merely the tip of the iceberg. Lane had systematically and almost maniacally gutted an excellent team even before those dastardly deals took place.

It had started in December. McLish and Billy Martin were sent to Cincinnati (known at the time as the Redlegs so as to avoid any notions of Communist leanings—seriously) for a veteran, banjo hitting second baseman named Johnny Temple. Meanwhile, Minnie Minoso-- whom Lane had acquired from Chicago in the ill-advised trade of Early Wynn and Al Smith just two years earlier—was returned to the White Sox along with a few throw-ins for veteran third baseman Bubba Phillips and two young prospects: catcher John Romano and first baseman Norm Cash.

Hello, I’m Norm Cash

When the Minoso deal hit the hot stove headlines, it dumbfounded many fans and sportswriters alike. While Minnie was certainly getting older, he had still put up a superb, Choo-like line in 1959 (21 HR, 92 RBI, .302 AVG, .846 OPS) as part of Cleveland’s intimidating corner outfield duo with Colavito (42 HR, 111 RBI, .257 AVG, .849 OPS). This made it hard to fathom why Cleveland would be willing to send one of their top offensive players to the team that had just edged them out for the pennant two months earlier.

When the Minoso deal hit the hot stove headlines, it dumbfounded many fans and sportswriters alike. While Minnie was certainly getting older, he had still put up a superb, Choo-like line in 1959 (21 HR, 92 RBI, .302 AVG, .846 OPS) as part of Cleveland’s intimidating corner outfield duo with Colavito (42 HR, 111 RBI, .257 AVG, .849 OPS). This made it hard to fathom why Cleveland would be willing to send one of their top offensive players to the team that had just edged them out for the pennant two months earlier.

In reality, though, Lane had arguably fleeced the rival Sox, stealing away two superior young talents in Cash and Romano, while selling high on an aging outfielder with only two more quality seasons in him.

The problem was that Lane himself would prove tragically unaware of the great deal he’d just pulled off. Rather than installing both Romano and Cash as bedrocks for the new-look Indians in 1960, Lane considered his newest acquisitions just two more pieces in a perpetually scattered puzzle.

For their part, both youngsters would survive spring training, with Romano beating out Russ Nixon easily for the starting catcher spot. Norm Cash, however, had a substantial blockade between himself and the first base job in Cleveland.

Vic Power had come to the Indians with Woodie Held two years earlier in another famous Frank Lane trade—the one that sent a young slugger named Roger Maris packing for Kansas City. Power was an all-star, but he was 31 now and had a track record of injuries and diminishing power numbers (he managed just 10 HR and 60 RBI in ’59). Even so, Lane saw Power as an immovable object at first base, making the 25 year-old Norm Cash an expendable commodity.

Meanwhile, with the lowly likes of the recently acquired Bubba Phillips and previous year’s starter George Strickland set to battle it our for the third base job, Lane set his sights on adding an upgrade at the hot corner before the season began.

Hello and Goodbye

Since Nick Punto hadn’t been born yet and free agency didn’t exist, Lane looked to the trade winds again for his third base answer. Toward the end of spring training, he was famously quite upfront about who his favorite target was. “I’d like to steal Steve Demeter from the Tigers,” he said. “He’s as good looking a right handed hitter as you ever want to see.”

And so, on April 12, 1960—just five days before The Rock said so long—the Indians announced another, comparatively unnoticed transaction with the Tigers. Lane had acquired his man-crush, Demeter, and only had to part with one of the young prospects from the Minoso deal, Norm Cash. Yup, Norm never played a regular season game with the Indians. But at least his 1960 baseball card catches a rare glimpse of him in the Cleveland cap.

Demeter and the Damage Done

Just a week after the trade, Demeter made his Indians debut on Opening Day at Cleveland Stadium, going 0-2 off the bench in a 4-2 loss to Rocky Colavito and the Tigers. Fortunately, Harvey Kuenn had a pair of hits for Cleveland while The Rock went 0-6 with 4 K’s and Norm Cash whiffed in his only plate appearance for Detroit. Lane looked all the wiser for a day.

Just a week after the trade, Demeter made his Indians debut on Opening Day at Cleveland Stadium, going 0-2 off the bench in a 4-2 loss to Rocky Colavito and the Tigers. Fortunately, Harvey Kuenn had a pair of hits for Cleveland while The Rock went 0-6 with 4 K’s and Norm Cash whiffed in his only plate appearance for Detroit. Lane looked all the wiser for a day.

And only a day. As it turned out, Steve Demeter might have looked good swinging a bat, but making contact with the ball was another issue. After appearing in just four games for the Indians and failing to reach base in any of them, Demeter was sent down to AAA Toronto in May to fine-tune his skills. He never sniffed a Major League clubhouse again. For the next 12 seasons, Demeter bounced around the Minors—Denver, Rochester, Tulsa— waiting for a phone call that didn’t come. Instead, his legacy became that of the “other guy” in one of the worst trades in Indians history.

Stormin’ Norman Cash, of course, went on to bigger and better things. Over the course of the 1960 season, he earned his way into the starting lineup as the Tiger first baseman and immediately started to show the power he’d hinted at in the White Sox system. In 353 at-bats, he managed 18 HR, 63 RBI, a .286 AVG and .903 OPS. Almost more incredibly, he didn’t hit into a single double play all year—a feat that had never been accomplished by a full-time player in league history.

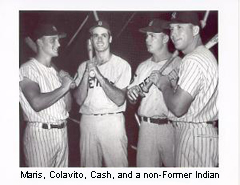

The Tigers were still a work in progress in 1960, but they now had one of the most feared middle-order trios in baseball: the celebrated Kaline, Colavito, and Cash. They also beat the Indians 15 of the 22 times they met.

The Curse of Norm Cash: The Fallout

The revamped Indians, predictably, sunk from contention. In the course of one week in April, they had kindly stocked the Tiger lineup for years to come while derailing their own fortunes for the next three decades. Along with Demeter’s disappearance from relevance, Bubba Phillips managed 4 homeruns and a .207 AVG as the club’s new third baseman. Johnny Temple posted a 2 HR, 19 RBI, .268 line as a seldom used bench player. Fourth starter Barry Latman posted a so-so 7-7 record with a 4.03 ERA. And Harvey Kuenn only drove in 54 runs, as his average dipped from .353 to .308. In December, he was unceremoniously traded again—this time to the San Francisco Giants.

John Romano—the other prospect from the Minoso trade—was at least one bright spot. Along with a cannon arm, he had some impressive pop at the plate for a catcher, slamming 16 homeruns and slugging a solid .475 in 1960. He would be an all-star the next two seasons, hitting over 20 homers and driving in 80 in both years.

John Romano—the other prospect from the Minoso trade—was at least one bright spot. Along with a cannon arm, he had some impressive pop at the plate for a catcher, slamming 16 homeruns and slugging a solid .475 in 1960. He would be an all-star the next two seasons, hitting over 20 homers and driving in 80 in both years.

Romano was good. Norm Cash was better. In 1961, the Tigers emerged as an elite AL team, winning 101 games (finishing second only to Maris’s Yankees). Al Kaline (19, 82, .324) and Colavito (45, 140, .290) lived up to their billing, but Cash was the breakout star. Though overshadowed by Maris's historic season in New York, Cash led the league in hitting at a .361 clip and added 41 HR and 132 RBI as he peppered the Tiger Stadium bleachers, and even cleared its roof (the first player to ever do so). The same year, Vic Power posted a line of 5 HR, 63 RBI, and a .268 AVG for a mediocre Tribe club (78-83) that could only wonder what might have been. No longer such an immovable object, Vic was traded to Minnesota before the 1962 season and retired three years later.

In fairness to Frank Lane, Cash was never again as dominant as he was in 1961. Years later, he admitted using a corked bat throughout that season. Still, Cash was a staple of the Tigers lineup for 15 years, finishing his career in 1974 with 377 homeruns (fourth most for a lefthander in baseball history at the time), 1,103 RBI, .271 AVG, and .862 OPS. He was also a 5-time all-star and a key member of Detroit’s 1968 World Championship club.

History Repeating

On the Indians end, the whole sad tale still had one more chapter left to be written-- long after the dust had settled on Frank Lane’s follies. In 1965, looking to add some power and (more importantly) sell some tickets, new Tribe boss Gabe Paul entered into a three way trade with Kansas City and, naturally, the Chicago White Sox, to bring back Rocky Colavito. Not surprisingly, an effort to rewrite history only wound up repeating it. The Indians sent a slumping John Romano back to the White Sox, but they also threw in a pair of prospects-- pitcher Tommy John and centerfielder Tommie Agee—who would go on to excellent careers. Meanwhile, an aging Colavito managed only two more decent seasons in Cleveland, making the deal a mirror of sorts to the Minoso trade of '59. In 1967, the Tribe dealt away The Rock again—with far less fanfare—to those ever wiling trade partners, the White Sox.

It’s hard to fathom how it must have felt being a Tribe fan in 1960, watching the power tandem of Colavito and Cash—who had been in your team’s spring training camp just months earlier—bashing for Detroit. I suppose it would almost be like having two Cy Young award winners on the same team, trading both of them, and then seeing them join forces again on the roster of a hated rival. Hard to imagine, isn’t it?