Every Cleveland Indians fan since 1937 knew Bob Feller. Not knew who Bob Feller was, knew him. Even if you never met him in person, you knew him.

Every Cleveland Indians fan since 1937 knew Bob Feller. Not knew who Bob Feller was, knew him. Even if you never met him in person, you knew him.

Feller was not only outspoken and opinionated, but he was also passionate about the game his whole life, from the time he first picked up a baseball in Van Meter, Iowa, until he tossed out the first baseball in the Tribe’s first spring training game of the season in Goodyear, Arizona. Since his retirement from the game in 1956, he has been an unrivalled ambassador for the national pastime in general and the Cleveland Indians in particular.

I had the opportunity to meet Feller in person, as did many avid Tribe fans. It was about 20 years ago. He was signing autographs at an East Side hotel where a small baseball card convention was being held. With my son in tow (he was about 10 at the time), we waited in a short line (fewer than a dozen people) near the end of the event, which was just clearing out. Feller dutifully autographed the photo my son presented him -- and then proceeded to talk our ears off for about five minutes, non-stop, regaling us with a few of his favorite memories.

That memory was almost photographic. He could not only tell you what pitch he threw to force Arkie Vaughn to hit into a double play in the 1939 All-Star Game, but he could also tell you the location of the pitch. He could tell you the final score. And he could probably tell you who had the winning hit.

Yet former Plain Dealer sports reporter Russell Schneider once asked Feller to name the most important game he ever won. “World War II,” he responded. Feller was the first major-leaguer to enlist in the military (U.S. Navy) after Pearl Harbor, even though his father was dying of cancer at the time and he could’ve gotten an exemption from active duty. Feller was stationed on the U.S.S. Alabama in the Pacific, earning eight battle stars and the Audie Murphy Award from the World War II Veterans Committee. “I’m very proud of my military record,” he often said. “We’re a free country.”

There are a million reasons why Feller’s statue stands outside Progressive Field. You know them all, from the three no-hitters to the eight All-Star Game appearances. Today, Indians VP Bob DiBiasio calls him “arguably, the best right-handed pitcher in baseball history.”

Feller was originally a shortstop for his American Legion team. But, he once claimed, “I started pitching because I couldn’t hit a curve ball with an ironing board.” Superscout Cy Slapnicka signed him to his first contract for $1 after seeing him pitch out in the Van Meter flatlands. (That contract, disputed by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, is still on display at the Bob Feller Museum in Van Meter.)

Here’s how big Feller was during his teen years:

>> He never played in a minor-league game.

>> In his first major-league appearance, he struck out St. Louis’s Leo Durocher, who disgustedly walked back to the dugout after two strikes. “Hey, Leo,” someone yelled, “you got one more.” The Lip answered: “You can have it. I don’t want it.” Feller ended up striking out eight members of the vaunted Gas House Gang in three innings of work that day.

>> He struck out 17 batters in a major-league game at age 17.

>> Returning briefly to Van Meter, he wore his Indians uniform to his high school class’s graduation. The ceremony was nationally broadcast on the NBC radio network.

Today, a pitcher who can hit 101 on the Jugs gun (and put the ball over the plate) is a phenom. Way back in 1946, Feller reportedly threw a ball 107.6 mph through a timing device with a strike zone in an exhibition at Griffith Stadium. That’s not a misprint: 107.6. (Wikipedia claims it’s the second-fastest pitch ever thrown, but I cannot find a recorded pitch anywhere -- including the Baseball Encyclopedia -- faster than 107.6.)

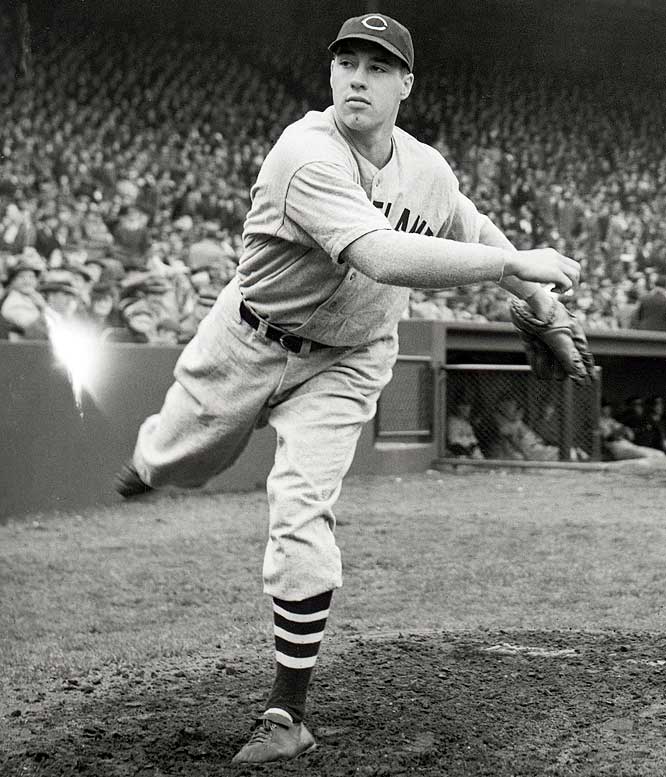

To attain such speeds, Feller’s high leg kick made it easy for opposing baserunners (yes, there were a few) to steal on him. But he corrected that later in his career and was elected to Cooperstown in 1962, his first year of eligibility.

During the Tribe’s final spring training in Winter Haven, Florida (and probably for many years prior), the team set up a table behind the left-field grandstand where fans lined up for autographs -- everyone from three-year-olds to 80-year-olds, male and female in equal numbers. I looked down from the top row of those bleacher seats every few innings during that spring three years ago, and he was there signing away, from the first inning to the last. The temperature that week was consistently in the mid-80s, but he was out there during every game I attended, all day. And he was chattering incessantly.

Sadly, I never saw No. 19 pitch in a real game, for he retired shortly before I became a Tribe fan. But I knew Rapid Robert; I surely did. We all did.

Robert William Andrew Feller: Nov. 3, 1918-Dec. 15, 2010