(Reminiscing) I threw the Red Dart, which broke sharply down left or right…

(Reminiscing) I threw the Red Dart, which broke sharply down left or right…

There was the Blue Bayou. I’d even tell the hitter I was about to throw it. I’d mouth the words slowly, which contrasted with the actual pitch- my best fastball.

The Riser was a fun, sidearm pitch. I could always get the hitter to swing at it, but it was feast or famine for me: it spun on a vertical axis, and was supposed to break upwards. If it did, it was an “out” pitch. If it didn’t, it just floated to the plate, looking like a ball on a tee to the hitter.

Then there was the roundhouse curve and the sweeping scroogie, which were basically the same pitch, only one was the exact opposite of the other.

Depending on which side of the ball the holes were on.

You’ve thrown some of these pitches- right?

The last pitch in my Wiffle Ball arsenal was another favorite of every kid I knew.

Everyone who’s played catch with any kind of baseball has dabbled with it: The knuckleball. The pitch without spin, which can break unpredictably on its way to the plate.

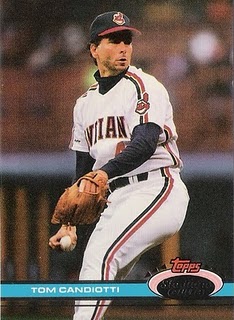

When Tom Candiotti began throwing his knuckleballs with the Cleveland Indians in 1986, there were only four starters in the major leagues who threw the pitch: Candiotti, Charlie Hough, and the Niekro brothers, Phil and Joe. 300 game-winner Phil was a fellow starter on the Tribe staff, and was a tutor for Candiotti as he mastered the pitch. At one point late in Candiotti’s career- when Charlie Hough retired- the Candy Man was the only knuckler in the bigs. Guys like Tim Wakefield, Steve Sparks and Dennis Springer eventually arrived to carry the mantle as practitioners of the craft.

So there has been a scarcity of knuckleball pitchers in the major leagues during various eras. This has caused some to lament the eventual extinction of the pitch, or to label it a fad. But the pitch has been around since before 1910. (What a fascinating time in the history of baseball, when all types of pitches were being invented. Rumors abounded at the time about who was throwing what, and where.) One description of a specialty pitch from that time was that of a “dry spitter”, but The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers notes that a photo of the baseball grip showed the first knuckles of the index and middle fingers touching the ball. (Of course, the traditional knuckleball grip eventually developed into the jabbing of the fingernails of the index and middle finger into the cover of the baseball.) The 1940s were perhaps the golden years of the knuckleball, when the Washington Senators starting staff featured four knuckleball pitchers. The Indians’ Gene Bearden, a hero of the 1948 World Series champions as a rookie, threw the knuckleball.

The pitcher’s game preparation focuses as much on fingernail trimming as on mechanics and arm strength and endurance. (It has been said that a spitball achieves the effect of a knuckleball. My feeling is that yes: the slippery area of a spitball makes the ball aerodynamically unstable, causing it to break suddenly on the way to the plate. But while a spitter may achieve the effect of ‘falling off the table’, a knuckleball can break down, sideways- and up. Sometimes even on the same pitch).

Almost never does a knuckleball pitcher start out as one. While chicks may “dig the long ball”, coaches of Little Leaguers on up to those in Legion ball dig the power arms. As Phil Niekro has noted, they either don’t want to fool around with a knuckleball pitcher, or don’t have the ability to teach the pitch. A pitcher gets scouted, and gets to the big leagues, by throwing hard. Not to mention that the pitch is hard to throw competitively. Niekro has in the past toyed with the idea of operating a knuckleball training school for average pitching talents (personally, I’d love to see it. I’d also be intrigued as to whether a female could find some big-league success **).

Almost never does a knuckleball pitcher start out as one. While chicks may “dig the long ball”, coaches of Little Leaguers on up to those in Legion ball dig the power arms. As Phil Niekro has noted, they either don’t want to fool around with a knuckleball pitcher, or don’t have the ability to teach the pitch. A pitcher gets scouted, and gets to the big leagues, by throwing hard. Not to mention that the pitch is hard to throw competitively. Niekro has in the past toyed with the idea of operating a knuckleball training school for average pitching talents (personally, I’d love to see it. I’d also be intrigued as to whether a female could find some big-league success **).

Knucklers can be very effective. I seem to recall the powerful 1990s Cleveland Indians lineup having trouble with them. Facing one seemed to put the offense into a funk for several days afterward. Of course, the flip side to this is that if the pitch is working, the catcher can have a terrible time trying to catch it- even with the oversized glove intended for the pitch. Such catchers often lead the league in passed balls. And if the pitch isn’t working, the knuckler is a slow gopher ball in-waiting, served up on a platter. And as Charlie Hough has said, how can a manager really know if a knuckleball pitcher is tired?

After all, the comparatively soft-throwing knuckleball pitcher is known for his endurance (Wilbur Wood, 24-20 in 1973 for the White Sox, threw 359+ innings and started both games of a doubleheader against the Yankees that year). The manager must be tough enough to give him some rope when he is struggling.

Tom Candiotti had bounced around as a minor league pitcher with the Kansas City Royals and the Milwaukee Brewers from 1979 to 1983. He experimented with the knuckler, until then-Royals minor league coach Gene Lamont instructed him to stop throwing it. (In other news, Gene Lamont would go on to become one of the 1990s White Sox managers whom the Tribe were responsible for getting canned, after sweeping the Southsiders.) In 1981, Candiotti suffered a common arm injury among pitchers- enduring a ‘pop’ in his elbow. For decades, pitchers with his injury (damage to the ulnar collateral ligament) were through with baseball due to pain and ineffectivenenss. But in 1974, Dr. Frank Jobe was pioneering the use of a tendon from another part of the body (like the forearm or hamstring) in replacing the damaged ligament. Tommy John was the subject of Dr. Jobe’s first experimental surgery- and it worked. However, the next seven 'Tommy John' operations didn’t ‘take’. The ninth player to try was Tom Candiotti. He actually had to convince the doctor he was a candidate. Dr. Jobe apparently didn’t want to perform the procedure on just anyone, and Candiotti was at that time only a prospect (he still sends Dr. Jobe a Christmas card every year, and signs it, “Your Prospect”). It took Candiotti about a year and a half to come back from the surgery- in his second start, he faced Tommy John. The surgery is now effective around 90 percent of the time, and Dr. James Andrews performs about 150 per year (mostly pitchers, but some position players, too- like Tribe right fielder Shin-Soo Choo in 2007).

When Candiotti earned a spot with the (allegedly- ha) big-league Milwaukee Brewers in 1983 and 1984, they told him that he’d always be an average major league pitcher at best. They knew he threw the knuckleball, and encouraged him to develop it by throwing it all the time. He was sent down to Triple-A and suffered a crisis of confidence- he was throwing the pitch while down in the count, issuing a lot of walks and losing a lot of games. In the short term, he was less effective than he’d have been throwing his slow curve, slow slider (which may have caused the elbow injury), and fastball. But concentrating on the knuckler would pay off in the long term.

Candiotti was released by the Brewers at the end of the 1985 season. The Cleveland Indians signed him, pairing him with Niekro. The 47-yr old ‘flutterballer’ was his typical humble, likeable self in discussing his relationship with Candiotti. He said they each learned knuckleball tips from the other. Notably, however, this was when the student learned from the tutor that a pitcher doesn’t need to throw the pitch when down in the count 2-0 or 3-0. Niekro had a curve for righties and a slider for lefties (breaking balls away, for each). Tom Candiotti’s repertoire became knuckler, slow curve, and fastball (losing the slider altogether).

Candiotti was released by the Brewers at the end of the 1985 season. The Cleveland Indians signed him, pairing him with Niekro. The 47-yr old ‘flutterballer’ was his typical humble, likeable self in discussing his relationship with Candiotti. He said they each learned knuckleball tips from the other. Notably, however, this was when the student learned from the tutor that a pitcher doesn’t need to throw the pitch when down in the count 2-0 or 3-0. Niekro had a curve for righties and a slider for lefties (breaking balls away, for each). Tom Candiotti’s repertoire became knuckler, slow curve, and fastball (losing the slider altogether).

Here’s something I just learned: In 1985, when Phil Niekro won his 300th game, he defeated the Toronto Blue Jays on the season’s final day. At age 46, he became the oldest to pitch a complete game shutout - and he didn’t throw a knuckleball until he faced the final batter. His Yankees were out of the playoff race, and he’d forewarned manager Billy Martin.

Tom Candiotti had some very good seasons with bad Indians teams in the late 1980s. From 1986 through 1990, he won between 13 and 16 games- with an ERA well below 4.00 every year but once. He was traded to the Toronto Blue Jays during the 1991 season along with outfielder Turner Ward, for outfielders Glenallen Hill and Hard Hittin’ Mark Whiten. Candiotti found himself on a contending team, playing in front of packed houses at Skydome.

That trade really bothered me at the time. Candiotti loved Cleveland. He grew up in northern California, but has told anyone who’s asked that he matured as a baseball player with the Tribe. In those days, with those teams, I saw no good reason to trade away an effective player who liked Cleveland. It turned out that John Hart actually knew what he was doing, clearing the decks of current and future high salaries like Candiotti's and Greg Swindell's as the franchise geared up for the opening of what would be called Jacobs Field, in 1994.

Candiotti pitched several seasons for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and a couple funny stories from his time there made their way back to the North Coast. My favorite: once, when Jeff Kent was playing with the New York Mets, Candiotti had a fantasy baseball team. Kent wasn’t on his team, and was partly responsible for his team’s poor results. With Ramon Martinez warming up in the bullpen to start a game against the Mets, Candiotti loudly mentioned to his pitching coach that he heard if Kent gets hit by a pitch early in the game, “he’s mush, for the rest of the series”. So during the game, of course, Martinez threw a fastball right into Kent’s ribs. He was hurt so badly that he had to come out of the game. Candiotti felt terrible. But then it became pretty humorous- Pedro Martinez, Ramon’s brother, also started pitching at Kent. Before long, all of the league’s Dominican pitchers just drilled him, the first chance they got. Ramon Martinez continued this for years!

The Candy Man pitched until age 41, when he was released by the Oakland A’s. Hart, always looking for help during the stretch drive for the pennant in the late 1990s, signed Candiotti to a contract during the 1999 season. Unfortunately, Candiotti had a bad knee which often required drainage and injections, and he had to shut the season down. Former teammate Bud Black had him try out with the California Angels in 2000, but Candiotti couldn’t answer the bell, and retired during Spring training.

Today, Tom Candiotti has various interests. He currently is a TV-radio analyst for the Arizona Diamondbacks. His bowling skill has earned him a place in the hall of fame for that sport. He is the second celebrity to earn that honor- the first having been former Notre Dame football star Jerome Bettis (I am unsure if Bettis ever played in the NFL… ha). He also played the role of knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm in the Billy Crystal film, 61*. Additionally, Candiotti proudly sports a collection of very elite baseball cards- the top 25 being recently valued at up to $7million.

** Please check out this link, which features the story of a girl in Florida who was unhittable while throwing the knuckleball. Her one-time teammate’s father, Joe Niekro, taught her the pitch. She throws it with three fingers on the ball. If you don’t know the story, I recommend watching the entire 9:34 video. Even if you are not an old-guy father of daughters, like me.

***Hey, follow me on Twitter! http://twitter.com/googleeph2 #thanks