The energy from within it lit up the ballpark, making it glow like a cruise ship floating out into Lake Erie.

The fans, who by all rights should have been marching back to their cars on this balmy spring night, were instead pounding their palms together, stomping their feet on the ancient concrete beneath them, and cheering at the top of their lungs.

The game was over, but they demanded a curtain call. And they weren’t leaving until these amazing Indians gave them one.

Even without the deafening din that surrounded them like a wall of sound, the players could feel the raw voltage of the crowd soaking through the dugout walls and knew what they had to do.

A moment later, they came up the steps and paraded back onto the field like heroes mounting a dais to receive their medals, and the crowd roared even louder. The players acknowledged the praise with applause of their own, along with towel-waving and jubilant salutes. Both the team and its fans were showing genuine appreciation for one another.

It was a magical moment, not only for the Indians, but for the city of Cleveland. For this postcard of victory came not from one of the many Mardi Gras-nights of the Jacobs Field era of the late ’90s, but from an otherwise ordinary Monday evening in May of 1986 – 25 years ago this week.

It was, for a city and a franchise at a crossroads, a game that catapulted a team into a memorable season. But more importantly, it was The Night That Saved the Indians.

This is My Team

Aside from new uniforms and caps that replaced the block “C” with Chief Wahoo, the Tribe looked basically the same as always to start the 1986 season.

Coming off a miserable 102-loss campaign the year before (preceded by seasons of 87 and 92 losses), the expectations were typically low. Sports Illustrated predicted the Indians would assuredly lose 100 games once again and placed them 24th overall in a power ranking of Major League Baseball’s 26 teams.

They did little to generate enthusiasm with a typical Indians start. After the bullpen imploded to turn a sixth-inning lead into a seven-run loss in Yankee Stadium, the Tribe stood at 7-8.

But more than just contemplating yet another sub-.500 season, as the end of April drew near, Cleveland baseball fans began to envision life without the Indians.

Reports revealed that after years of spending too much money on high-priced players who never delivered while the team struggled at the gate, the Indians were in serious financial trouble. Even baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth admitted that the franchise was in dire straits. After decades of rumors, it was now closer to reality than ever: the Indians were on the brink of moving from Cleveland.

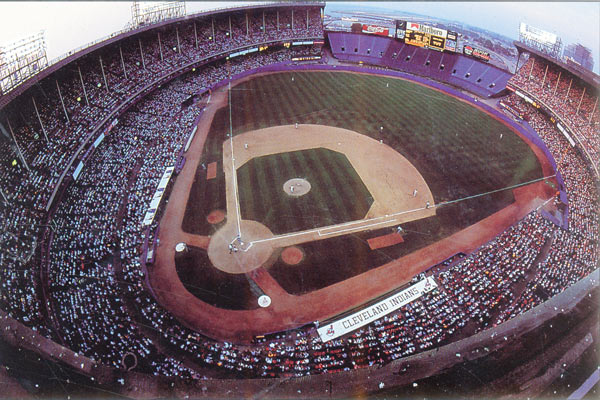

Attendance had been and continued to be downright embarrassing. In 1985 the team averaged just over 8,000 fans per home game. The home opener – which more often than not represented about 10% of the season total – tallied a disappointing 32,000 in ’86, and the trend continued when a three-game series against the Orioles a week later drew a total of just over 9,000 fans. Rubbing salt in the wound, the much-ballyhooed domed stadium proposal whipped up three years earlier to save the franchise was going nowhere.

Put it all together and it was just about what you’d expect from a franchise owned by a dead guy.

Technically the team belonged to the estate of the late Steve O’Neill, who’d died in 1983. Now his family was shopping the team, and there was a better than even chance that whoever bought it would yank it out of Cleveland and not look back.

With all of these factors swirling together to form a tempest of frustration and uncertainty in the spring of ’86, Cleveland Mayor George Voinovich snapped.

Throwing together a hastily prepared press conference, Voinovich pledged his undying support for the Indians and threw the Plain Dealer under the bus, blaming the paper for poisoning the public against the Indians by printing only the bad news that discouraged fans from supporting the team. He was dramatic and emphatic, pointing his finger at the reporters in attendance and scolding them, all while sitting in front of a backdrop emblazoned with the Indians’ unintentional whiny-child slogan of “This is My Team!”

For all his good intentions, the mayor came across as silly at best, naive at worst. “It’s not the media that are killing the Indians,” a letter to the PD stated. “It’s the Indians that are killing the Indians. Give us, the fans, a winner and we’ll back them up. Give us a loser and we’ll die.”

Whomever he thought was at fault, Voinovich saw his city’s team dying and clearly didn’t want to be known as The Mayor Who Lost the Indians. He proclaimed the Friday night of Memorial Day weekend to be “Citizens Day” at Cleveland Stadium and challenged fans to show their appreciation for the team by coming out to the park that night.

His goal was 35,000 fans, which sounded ridiculously over-ambitious. Take away the home opener attendance total - itself 3,000 fans short of Voinovich’s goal - and the Indians were only averaging 6,600 per home game. Unless Voinovich promised income-tax amnesty for all who came to the park on May 23, there was no way that he was going to entice 35,000 fans out to dingy, dank Cleveland Stadium to watch a lousy team simply by trying to make it their civic duty.

But then, the day after news of his bizarre press conference hit the streets, the Indians did something completely unexpected.

They started to win.

The Streak

It started quietly.

They bounced back from a pair of disheartening losses to New York and beat the first-place Yankees twice in the Bronx. They went to Texas and took another pair – once rallying from three down in the eighth. They then trailed in the eighth inning in three straight games in Chicago but came back to win them all, twice going to extra innings.

Suddenly the Indians had won seven straight, all on the road, and pulled ahead of the Yankees and into first place in the American League East Division. “First place,” Paul Hoynes wrote to lead his game story in the following day’s paper. “Can you believe it?”

Many couldn’t. A week earlier, the primary topic surrounding this team was how much longer it could survive in Cleveland. Now the Indians were atop their division and were the talk of the town.

“What else is there besides winning?” outfielder Joe Carter had said midway through the winning streak. “If you win, you solve everything.”

In this case, Carter’s statement was more telling than he ever could have known, for they came home to a different city on Monday, May 5.

That afternoon, a massive rally was held at Burke Lakefront Airport to celebrate the announcement that Cleveland had been selected as the site of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Presiding over the rally was a glowing George Voinovich.

“Cleveland is the home of the All-American City,” he declared. Then he added to the crescendo with a proclamation that prompted more cheers than the Rock Hall announcement: “It’s the home of the first-place Indians!”

The Night That Saved the Indians

That evening, they would face the defending world-champion Kansas City Royals, and no one was quite sure what to expect at the box office. The Tribe had become a major topic around town, so much so that even people who didn’t follow baseball knew that the Indians were winning and were interested to see if they could keep it up. But would it translate to ticket sales?

Team president Peter Bavasi expected a big crowd, maybe 12 or even 15,000, which would have been a dramatic improvement over their last Monday-night home game, which drew just 3,012 lonely souls.

But what Bavasi saw a half-hour before the game shocked him.

The line of fans waiting to buy tickets stretched from Gate A all the way back to City Hall. Stadium officials quickly opened as many ticket windows as possible but still the line crawled at a snail’s pace. The start of the game was moved back 15 minutes. Franchise emissary Bob Feller was sent out to mingle with the patiently waiting fans. Feller later would say it was as ramped-up a crowd as he’d seen since the 1948 pennant chase.

Though it was estimated that nearly 10,000 fans succumbed to impatience and frustration and went home, the majority hung in there – a fitting slice of symbolism for the franchise itself.

The final tally was 27,118. It may not have sounded like much outside of Cleveland, but to the Indians and their beleaguered fan base, it was nothing short of miraculous – if not completely incredulous. During the game, Indians’ Public Relations Director Bob DiBiasio got a call from a doubtful American League Executive Vice President to confirm the attendance figure he’d seen and hadn’t quite believed.

Some figured it was the largest weeknight crowd in May in at least 20 years. And had the Indians been better prepared for the throng of fans waiting to buy tickets, the crowd may have crept up over 35,000.

And each and every one of them who stayed enjoyed a show never to be forgotten.

Trailing by one in the ninth, Cleveland center fielder Brett Butler sliced a two-out line drive off of Royals’ stud closer Dan Quisenberry to score Otis Nixon and  send the game to extra innings. Then, after 47-year-old knuckleballer Phil Niekro – signed by the Indians a month earlier – shut down the Royals in the 10th, Tribe first baseman Pat Tabler smashed a liner off the chest of Kansas City second baseman Frank White to bring home Joe Carter from third with the winning run.

send the game to extra innings. Then, after 47-year-old knuckleballer Phil Niekro – signed by the Indians a month earlier – shut down the Royals in the 10th, Tribe first baseman Pat Tabler smashed a liner off the chest of Kansas City second baseman Frank White to bring home Joe Carter from third with the winning run.

As Carter crossed the plate, the crowd went utterly berserk and refused to leave the park, even though clocks were inching toward 11 and everybody had to go to work in the morning. It didn’t matter. Reality had been abandoned for this one perfect moment.

As the players took their well-deserved curtain call, the reality of the situation began to sink in. Niekro, in his 23rd season, admitted he’d never seen anything like this. “You could just feel it coming right into the dugout,” he said. “It sounded like there were 72,000 people out there.”

“I loved it, it was beautiful,” second baseman Tony Bernazard said later. “This is what this city and this team needs.”

Columnist Bob Dolgan put it even more succinctly in the next day’s Plain Dealer:

“Cleveland came back as a major league baseball city last night.”

A Summer to Remember

But the Tribe wasn’t done. It won a rain-shortened game the following night, then clobbered defending Cy Young winner Bret Saberhagen on Wednesday to complete the sweep and run the winning streak to 10.

“Fasten your seat belts,” Dolgan wrote. “It is beginning to look like this is going to be a memorable baseball season in Cleveland.”

It was.

On Friday night, with the White Sox in town and Wheel of Fortune goddess Vanna White on hand to throw out the first pitch, more than 48,000 packed into Cleveland Stadium – the biggest non-home opener crowd in three years. Though the Indians blew a two-run lead in the ninth to lose and end the improbable streak, the appreciative fans gave them a standing ovation when the game was over.

“We’ve awakened the sleeping giant,” Butler said later.

The ’86 Indians fell out of first place that night and would never return. They struggled throughout the rest of May, losing 19 of their next 26 and soon were in last place once again. But the Tribe fever that had gripped the city earlier that spring didn’t fade away, and neither did the Indians, who continued to win despite their on-paper disadvantage.

“The Cleveland Indians are the misfits,” outfielder Mel Hall proclaimed at one point. “We’re the guys nobody else wanted.”

And they were embraced by their hometown. On George Voinovich’s “Citizens Night” that kicked off Memorial Day weekend, when he’d dreamed of luring 35,000 to watch the Indians, more than 61,000 turned out. And they didn’t come because the mayor asked them to.

As the temperatures warmed, so too did the Cleveland offense, and by Independence Day, the Tribe had climbed back up over .500 to stay. That night at the Stadium, 73,303 - the largest crowd in all of baseball in 1986 - watched Phil Niekro pitch a complete game in a rout of Kansas City.

The good times continued to roll all summer as the streaky Tribe always managed to remain entertaining. A string of 10 wins in 12 games helped pull the Indians to within five games of the first-place Red Sox in late July before another slump took them out of contention for good.

When they finished strong, winning their last four games to come in at 84-78, the Indians clinched their best record in 18 years and a whopping 24-game improvement from the year before – the most dramatic turnaround in franchise history. More importantly, they had provided the city with its best baseball season since the pennant chase of 1959. The talk of the team leaving ceased and the stories about their financial difficulties were replaced by accounts of their on-field heroics.

And the players, virtually unknown outside their own clubhouse the year before, became matinee idols.

While the overall pitching was as sub-par as expected, it was buoyed by unexpected contributions from the knuckleball duo of Tom Candiotti and Phil Niekro, who were both acquired for pocket change just before the season began and combined for 27 wins and 22 complete games. Colorful closer Ernie Camacho bounced back from a serious elbow injury to pick up 20 saves. Ken Schrom, acquired in a quiet trade with Minnesota the previous winter, won 14, and a rookie fireballer named Greg Swindell was drafted in June, debuted with the Indians in August, and wound up winning five games.

But the heart of this team was its high-flying offense. The Indians led the American League in runs, hits, batting average, slugging percentage, and stolen bases. They scored more than any Tribe team since the ’48 world champs and had a higher batting average than any Cleveland club in a half-century. Seven players knocked in 60 runs or more, led by outfielder Joe Carter, who led the league with 121 to go along with 29 homers and a .302 average.

Brett Butler stole 32 bases and emerged as one of baseball’s top center fielders. Rookie Cory Snyder belted 24 home runs in just over 100 games. Pat Tabler  turned in the finest season of his career, hitting .326.

turned in the finest season of his career, hitting .326.

But maybe the best things to happen occurred off the diamond. For one, the 1986 team drew 1.4 million fans to Cleveland Stadium – its highest total in 27 years and more than twice its tally from each of the previous two seasons.

Then, in December, the team – now having demonstrated its upside and potential popularity – was purchased by Richard and David Jacobs, who finally brought the stability and accountability to the front office that had been lacking for three decades.

The Legacy of ’86

Yet the long-term positive changes the Jacobs brothers would instill were still well down the road. With expectations soaring going into 1987 – encapsulated by the infamous Sports Illustrated “Indian Uprising” cover – the Indians returned to their losing ways, becoming the only team in baseball history to sandwich a winning season between two 100-loss seasons. Seven consecutive losing records would follow until 1994 arrived and changed everything.

But through all the lean years that followed 1986, including seasons of 101 and 105 losses, the Indians would never again fail to draw a million fans – after doing so only four times in the quarter-century prior to 1986.

Things were different after that exciting summer. Afterward, because of that out-of-nowhere season, even when the Indians were lousy there was still a glimmer of interest generated by fans actually having a first-hand memory of an entertaining Tribe team.

Make no mistake, the 1986 squad was not a great one. Nor was its season legendary or something out of storybook. And it’s possible the Indians’ future may have unfolded exactly the same had 1986 been just another melancholy march from April to October.

But the timing of the Indians’ 10-game winning streak that spring and the randomness of such a spirit-stirring season in the midst of so many awful ones precisely when the city and the team needed it most suggests there was something mythical, almost ethereal about what that team accomplished that summer.

What happened that Monday night 25 years ago this week may well have altered the course of the franchise. Had the Indians not embarked on a completely shocking winning streak – and the fans not showed their appreciation for it – it is very easy to visualize the franchise crumbling to bits and blowing away in the Lake Erie breeze.

Even after the excitement of the moment passed, the memory of the raw emotion in the Stadium that May evening persevered. Five months later, Bob Dolgan wrote, “In 40 years of watching baseball here I have never seen the frenzied mania that was present that night. Even if the Indians go on to win a World Series someday, it is doubtful if that kind of emotion will ever be felt again. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, worth the whole season.”

The true once-in-a-lifetime experiences and the sparkling new ballpark that would host them were still a decade away, but made possible in part by the Incredible Indians of 1986 and the magic that began that Monday night in May.

Perhaps the best example of the viral impact of the Indians’ hocus-pocus in ’86 occurred just minutes after the final out of their final game.

A half-hour after their spirited season came to a close, their housemates, the Browns, picked up the Indians’ torch and used some sorcery of their own to break the infamous and enigmatic 16-year Three Rivers Stadium Jinx. The impossible was suddenly possible in the kingdom of Cleveland sports.

But that’s – as the old cliché goes – another story.

This is the third in a series of articles celebrating the 25th anniversary of the amazing Cleveland sports calendar year of 1986.