Here’s a quick trivia question: In 1972, as a ten-year-old little league ballplayer, my chosen number was 8. Which big-leaguer would you say this was based on? Answer below.

Here’s a quick trivia question: In 1972, as a ten-year-old little league ballplayer, my chosen number was 8. Which big-leaguer would you say this was based on? Answer below.

Jersey numbers have held significance in Baseball since the New York Yankees became the first team to permanently wear them in 1929. The numbers of the starting position players reflected their spots in the batting order. Earle Combs was 1, Mark Koenig was 2, Lou Gehrig was 3, Babe Ruth was 4, Bob Meusel was 5, Tony Lazzeri was 6. As early as their historic 1927 season, they were known as Murderers’ Row.

The answer to the question above? You are correct: it was Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski. (Either I was too young to know better, or the Boston Red Sox had yet to embody evil itself- ha.) Yaz had won the American League Triple Crown in 1967 (leading the league in batting average, home runs and runs batted in. It’s a rare feat which had been accomplished by Baltimore Oriole Frank Robinson the season before, but has not been achieved since.).

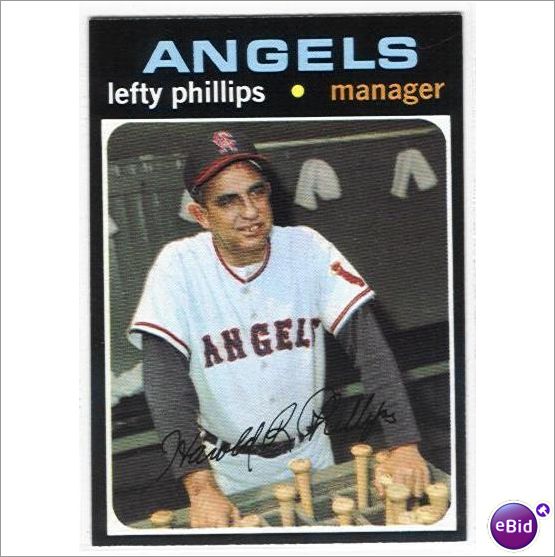

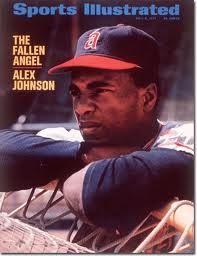

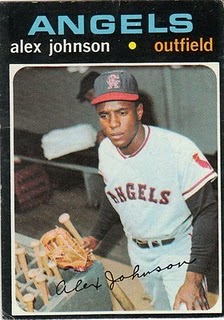

In 1970, the A.L. batting title came down to the final days of the season. Yastrzemski was neck-and-neck with California Angel Alex Johnson. Johnson had two hits on the final day of the season vs. the Chicago White Sox, which lifted him past Yaz by percentage points. In a move which surprised Johnson, manager Lefty Phillips removed him from the game after his second hit. Johnson ended up with the batting crown.

In 1970, the A.L. batting title came down to the final days of the season. Yastrzemski was neck-and-neck with California Angel Alex Johnson. Johnson had two hits on the final day of the season vs. the Chicago White Sox, which lifted him past Yaz by percentage points. In a move which surprised Johnson, manager Lefty Phillips removed him from the game after his second hit. Johnson ended up with the batting crown.

One can imagine how this went down in Beantown. Red Sox fans had witnessed Ted Williams’ legendary season of 1941: Williams had hovered near or above the historic .400 mark the entire year, and stood at .39955 with two games to go: a doubleheader vs. the Philadelphia Athletics. He knew if he sat out that final day, he’d be credited with the .400 average for the season. Baseball fans know he chose to play, and went 4 for 6 on the day to finish at .406. (Of note, this was also the year of Joe DiMaggio’s 56 game hitting streak.) So it did not matter that leaving that 1970 game was not Alex Johnson’s idea; the fact was that he did not stay in the game and risk dropping his average. The result was he won the title over the Red Sox star- the man who’d succeeded Ted Williams, playing left field in Fenway Park.

To a wide-eyed ten-year-old, Alex Johnson beating out Carl Yastrzemski for the batting title was huge. To me, this did not make him a villain. He was a curiosity, a guy who could be another hero. However, something just did not feel right about that guy. Coverage of him in the print media ranged from discomfiture to disdain. Very confusing to a kid, to which Major League Baseball was the embodiment of challenging, fun competition.

Alex Johnson had broken into the major leagues with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1964, after breezing through the minors upon declining a football scholarship with the Michigan State Spartans. (His younger brother Ron had been a Michigan Wolverine, and was an NFL running back for the Cleveland Browns before being traded to the New York Giants). Powerfully built, Johnson was a natural born hitter (labeled “Bull“ as a minor leaguer), although his adventures patrolling the outfield were subpar (he was dubbed “Iron Hands“ in spring training with the Phillies).

The Phillies grew tired of what was apparently a poor attitude and a lack of effort. He played various portions of two seasons in Philly, facing mostly righthanded pitching at first.

Near the end of the 1964 season, the Phillies held a 6 ½ game lead with 12 to play. Facing Cincinnati in a scoreless game, Reds infielder Chico Ruiz was on third base. Even though their best hitter, Frank Robinson, was at the plate, Ruiz broke for home.He was safe, and the Reds won, 1-0. Phillies manager Gene Mauch was so incensed by this breach of baseball etiquette that he hollered at Ruiz during the game the next day, and the Philly pitcher threw a pitch into his ribs in his first at-bat. Something changed with the Phils the day Ruiz stole home; they lost ten straight games, and a sense of doom turned to panic as they blew the pennant in historic fashion. Some said the team was wracked with dissension; others maintained Mauch had made the wrong moves.

In 1965, the Phillies traded Johnson to the St. Louis Cardinals, who suggested they’d duplicate the success they’d enjoyed when the acquired Lou Brock.

Brock had been a Chicago Cub until 1964, when he was traded to the Cardinals. The other principal in that trade was pitcher Ernie Broglio, who’d led the N.L. in wins in 1960 for St. Louis. He was coming off of a 1963 season in which he'd won 18 games . As my cousin Risa (Card fan), and her husband Jeremy (Cub fan) may know: while Broglio had little success with the Cubs, Lou Brock became a Cardinal legend. He not only helped the Cardinals transition from the retirement of Stan Musial in 1963, he helped them to three World Series appearances from 1964 through 1968. The Cards won two titles during that stretch. Sorry Jeremy- I'm sure Ernie Broglio had many socially redeeming qualities as a Cub, as well.

The Cardinals grew weary of Alex Johnson, who’d struggled at the plate and still was perceived as a player with a sour attitude who played with less than full effort. They traded him to the Cincinnati Reds.

Johnson blossomed as a hitter with the Reds. He hit over .300 in 1968 and 1969; finishing no lower than sixth in the league each year. The Reds’ Bob Howsam was assembling the powerful Big Red Machine in Cincinnati, and he had a surplus of hitting. He needed pitching, and dealt Johnson to the California Angels for starter Jim McGlothlin and reliever Pedro Borbon prior to the 1970 season.

1970 was the year Alex Johnson won the American League batting title, edging out Yastrzemski. But all was not well in Anaheim. Johnson failed to run out ground balls, played singles into doubles in the outfield, and actively avoided getting along with his teammates. He was repeatedly fined by management and by the players’ ‘kangaroo court’ for not giving his best. Throughout, Johnson acted as though the hard feelings and disciplinary actions did not affect him in the least.

1970 was the year Alex Johnson won the American League batting title, edging out Yastrzemski. But all was not well in Anaheim. Johnson failed to run out ground balls, played singles into doubles in the outfield, and actively avoided getting along with his teammates. He was repeatedly fined by management and by the players’ ‘kangaroo court’ for not giving his best. Throughout, Johnson acted as though the hard feelings and disciplinary actions did not affect him in the least.

It was in 1971 that the baseball world crashed down around Alex Johnson. His insubordinate activities broadened: during one spring training game, he positioned himself in the shade of the outfield fence rather than where he was supposed to be. He reportedly moved throughout the game according to where the shade was cast from a light standard. During the regular season, he was benched for a lack of hustle by Phillips. The team rejoiced in this stand being taken by their manager. General manager Dick Walsh then failed to back up Phillips, and had Johnson reinstated to the lineup. Teammate Chico Ruiz became a lightning rod, a focal point of confusing contradictions. Johnson and Ruiz had also been teammates with the Reds, and Ruiz was the godfather for one of Johnson’s children. They had been traded together to the Angels. But their friendship deteriorated to the point that Johnson would scream obscenities at Ruiz whenever they were near each other. Walsh was actually quoted as saying Ruiz was good for Johnson- he needed someone to pick on.

One day, after Johnson and Ruiz had each pinch-hit in a game, they each went to the clubhouse. Johnson reportedly dashed out and found a security guard, and told him that Ruiz had pointed a gun at him. When this story reached the press, Ruiz and Walsh denied it.

Finally, Alex Johnson was suspended again, indefinitely, for failing to run out a ground ball one too many times.

Finally, Alex Johnson was suspended again, indefinitely, for failing to run out a ground ball one too many times.

Marvin Miller and the fledgling players’ union seized upon the Alex Johnson situation with the Angels. Miller was outraged that the team suspended and fined the player without evaluating his emotional health. He hired a psychiatrist, who determined Johnson was emotionally disabled. The league hired its own psychiatrist, who agreed. The union won the case, which had gone before an arbitrator who held that Johnson should have been put on the disabled list rather than suspended.

It was at this hearing that the truth came out about Chico Ruiz and the accusation of the threat with a gun. Walsh finally admitted that the story was true (his lame excuse was that he acted in the interest of the team, that Ruiz was not a U.S. citizen and might have been deported to Cuba, and that oh-by-the-way the gun wasn‘t loaded). The gun story not only had been scoffed at nationally for three months, in print- but Walsh had personally called Johnson‘s pregnant wife to claim her husband was delusional. Walsh also had lied to other Angels players when he’d told them the union was requiring them to testify.

So the Angels were an unstable mess. Their players did not stick together, nor did they have the back of Alex Johnson (during the gun controversy, they were seen staging mock ‘shootouts‘ in hotel lobbies. One player reportedly told the press that he wished the gun had been loaded). And they already had a reputation from the 1960s as being a racist franchise.

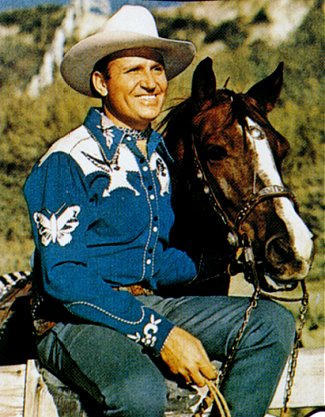

This is curious, since their owner was singing cowboy Gene Autry. A radio and movie icon of the 1940s and 1950s, so many youngsters followed him that he put together a famous Cowboy Code:

This is curious, since their owner was singing cowboy Gene Autry. A radio and movie icon of the 1940s and 1950s, so many youngsters followed him that he put together a famous Cowboy Code:

1) The Cowboy must never shoot first, hit a smaller man, or take unfair advantage.

2) He must never go back on his word, or a trust confided in him.

3) He must always tell the truth.

4) He must be gentle with children, the elderly, and animals.

5) He must not advocate or possess racially or religiously intolerant ideas.

6) He must help people in distress.

7) He must be a good worker.

8) He must keep himself clean in thought, speech, action, and personal habits.

9) He must respect women, parents, and his nation's laws.

10) The Cowboy is a patriot.

From a quick glance, it appears that maybe 4 or 5 of those items may have been ignored by GM Dick Walsh.

As for Marvin Miller, it’s been said he was proud to be able to show black players that they would have union protection, as would white players.

Personally, while Johnson was treated shamefully by the Angels, I believe he was also used by Marvin Miller to advance his union agenda. It just so happened that Johnson’s interests were served by Miller‘s personal motives.

Johnson’s mental and emotional makeup as a player seem obviously vulnerable now- even to non-psychiatry-professional hacks like myself. Quotes from his early days seem to betray a fragile confidence. After he’d played a few years in the majors, he became outwardly hostile- berating teammates, ignoring managers, and intimidating umpires.

And sports journalists as well, who would exact revenge by publishing scathing comments which accelerated the vicious cycle. Baseball Digest (which by the way is available to read for free on Google Books through the September 2009 issue) features a couple of easily-accessed examples.

While Johnson may have required psychiatric care, it might be noted that Johnson was more successful as a ballplayer when he was left alone than when he was hounded unmercifully. At least, this seems obvious when looking at his good seasons with the Reds vs. the troubled time in Philadelphia and the disaster in Anaheim.

There was another side to Alex Johnson, the man who loved children and donated time and money to charities. He was said to have been extensively involved on their behalf, during times when the public was unaware. A variety of sources have corroborated this.

Chico Ruiz died in February of 1972, when his car hit a sign pole in San Diego. Alex Johnson was said to be one of the few players who attended his funeral.

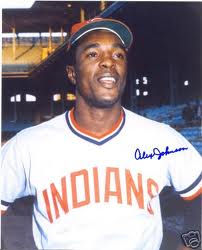

So- how does this article become a piece which features the Cleveland Indians?

Prior to the 1972 season, Alex Johnson was traded to the Tribe. The Cleveland franchise had been sold that offseason, in a fateful move in which former owner Vernon Stouffer (pioneer of the frozen foods industry) chose a slightly higher bid from Nick Mileti over one from George Steinbrenner.

Observers today feel that had Steinbrenner’s bid been successful, the history of the Indians would have been much different over the ensuing decades. Upon Steinbrenner’s recent death, the Plain Dealer’s Bob Dolgan noted how Steinbrenner acknowledged his family would have had the Tribe on an arc similar to the one his Yankees enjoyed in the late 1970s and 1980s. Dolgan also reminded that while 90s Indians owner Dick Jacobs was motivated by a successful bottom line, Steinbrenner was driven to win.

The Indians would soon consider an option of playing some of their “home” games in New Orleans; they scrapped this plan after facing stiff opposition in Cleveland. But the team was still suffering from poorly funded ownership.

Alex Johnson was a perfect low-risk/high-reward type of player for the franchise in 1972. G.M. Gabe Paul admitted every trade is a gamble, but if they hit on this one, they’d hit it big. Besides, they didn’t really give up much for him (trading the future away didn’t begin to occur until the next few seasons, when they’d serve it up on a platter to the Yankees- and their new G.M., Gabe Paul. Largely because they desperately needed the cash which was included in those deals).

Johnson started out the season well. He was hitting, and making the required plays in the field. Gerry Moses, the catcher who came to the Indians in the Johnson trade, commented on how the team just left Johnson alone, and it was working well. The Indians began winning games. They were in first place in mid-May. The starting pitching featured rookie Dick Tidrow, Milt Wilcox, and that year’s A.L. Cy Young award winner, Gaylord Perry. Perry and slick-fielding shortstop Frank Duffy had come to Cleveland in another trade, the one in which they shipped troubled and disgruntled pitcher Sam McDowell to the San Francisco Giants. Graig Nettles was the promising third baseman, and another rookie, budding star Buddy Bell, manned right field.

Johnson started out the season well. He was hitting, and making the required plays in the field. Gerry Moses, the catcher who came to the Indians in the Johnson trade, commented on how the team just left Johnson alone, and it was working well. The Indians began winning games. They were in first place in mid-May. The starting pitching featured rookie Dick Tidrow, Milt Wilcox, and that year’s A.L. Cy Young award winner, Gaylord Perry. Perry and slick-fielding shortstop Frank Duffy had come to Cleveland in another trade, the one in which they shipped troubled and disgruntled pitcher Sam McDowell to the San Francisco Giants. Graig Nettles was the promising third baseman, and another rookie, budding star Buddy Bell, manned right field.

But the season was not to be a winner for the Indians in 1972. Alex Johnson slid back into his pattern of not hustling, and generally doing things which force a manager to bench a ballplayer. In particular, one player mentioned that he occasionally spent an entire plate appearance without any intention of ever swinging the bat. He’d simply walk back to the dugout after having struck out, apparently without remorse. Another time, a teammate commented on Johnson bunting in eight straight at-bats, including several times when bunting was not warranted. Manager Ken Aspromonte sat Johnson down during the final month of the season. Johnson finished with an average of .239 and with only 37 RBI.

Johnson wound down his career by continuing to bounce from team to team. G.M.s were convinced he could play, and he got chances with the Texas Rangers, the New York Yankees and his hometown Detroit Tigers. His relationships with managers such as Whitey Herzog and Billy Martin were spotty, and he played his last major league game in 1976. Johnson actually remained in baseball for a time after his release from the Tigers, playing with the Mexico City Reds.

He retired, joining his father’s truck service shop in Detroit. Visited by Sports Illustrated in 1998, Johnson said, “Do I enjoy my life?…I enjoy not having to face everything I did.”

So, what is the explanation for why Alex Johnson, the star ballplayer who spent a year with the Cleveland Indians, was so morose and bitter?

Some things are hard to figure out as a youngster. Sometimes, when he grows up, he discovers answers. Other times, there are no easy answers. Such was the case of Alex Johnson.

Thank you for reading. Next week: Blast From The Past: Bobby Avila.