As a Cleveland Indians fan coming of age in the 1970s, I wasn’t especially enamored with their previous eras of success. Call it more of a detached curiosity.

As a Cleveland Indians fan coming of age in the 1970s, I wasn’t especially enamored with their previous eras of success. Call it more of a detached curiosity.

My Indians always had the specter of relocation hanging over them like a gathering gloom. It seemed all of their promising young players were traded away (this is still a backdrop to fan attendance, in the post- CC, Victor, and Lee era). The key to those 1970s trades often was the cash the Tribe received in return. Such infusions of money were crucial in their ability to honor basic financial obligations.

Around 1974, the Tribe was in the middle of a historically horrible run of failure. Yet it had only been twenty years since the Indians won their league pennant and gone to the World Series. Twenty years- shoot, that’s about equals the elapsed time from the pre-Jacobs field era of Hank Peters and John Hart to the present day. It’s not that much time at all.

Yet the Cleveland Indians of 1954 were light years removed from the 1974 edition. While I loved the Tribe, I was conditioned to constant player turnover, fan apathy and team futility. But that 1954 team… did they actually win 111 games in a 154-game season? Yes, and the second-place Yankees won 100- finishing eight games back.

The Yankees were in the midst of their ‘50s dynasty. They had won the pennant in ‘51, ‘52, ‘53, and would win in ‘55 and ‘56. The 100 games the Yankees won in 1954 was more than they won in any of those other years.

Baseball historians describe the pitching staff of the 1954 Indians as perhaps the best ever. Starting pitchers Bob Lemon and Early Wynn each won 23 games; Mike Garcia won 19 and led the league in ERA (Lemon and Wynn were second and third). Bob Feller was on the downside of his career, yet went 13-3. Art Houtteman won 15. In the bullpen, Ray Narleski and Don Mossi were the league’s dominant righty-lefty duo. Hal Newhouser was also a star in the pen, adding a Cleveland chapter to his long career as a Detroit Tiger. Lemon, Wynn, Feller, and Newhouser are all in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The everyday lineup was solid. Bill Glynn and Vic Wertz at first. George Strickland at short. Al Rosen at third. Al Smith in left, Dave Philley in right. AL home run and RBI champ Larry Doby in center. Jim Hegan was the catcher, and even the backups were well-known: Dave Pope in the outfield spelling Philley, and Sam Dente, Hank Majeski and Rudy Regalado in the infield. The low-key manager was Al Lopez.

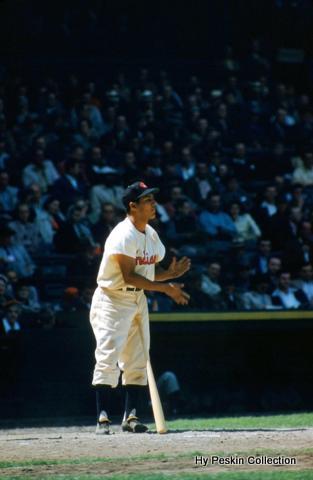

You know that the 1954 Cleveland Indians were swept by the New York Giants in the World Series. History has seemed to record it as a one-sided affair, symbolized by Willie Mays’ catch in Game One. But the first two games could have gone either way. Wertz’s drive which Mays caught would have been a home run most anywhere else but at the Polo Grounds, and Giant Dusty Rhodes’ home runs there would have been outs anywhere else. Game Three was not lopsided. (Side note: the Avila/Mays photo to the left was apparently taken in Cleveland. Might have been prior to Game Three.) Although Game Four was, as the Tribe pitching collapsed.

You know that the 1954 Cleveland Indians were swept by the New York Giants in the World Series. History has seemed to record it as a one-sided affair, symbolized by Willie Mays’ catch in Game One. But the first two games could have gone either way. Wertz’s drive which Mays caught would have been a home run most anywhere else but at the Polo Grounds, and Giant Dusty Rhodes’ home runs there would have been outs anywhere else. Game Three was not lopsided. (Side note: the Avila/Mays photo to the left was apparently taken in Cleveland. Might have been prior to Game Three.) Although Game Four was, as the Tribe pitching collapsed.

Also: interesting that the city of Cleveland couldn’t really be said to have had ‘pennant fever’ in 1954. Back in the World Series Championship year of 1948, the Tribe was in a tight pennant race, and drew over 2.6 million fans. The 1954 team drew over 1.3 million. Doby was asked by Baseball Digest in 1979 about that, and he noted that the Indians’ fans were good, and knowledgeable- but older, more mature and less emotional than fans in some other cities. And the ‘54 race was a runaway, with no suspense. (Huh. Cleveland fans of any sport in the 1970s were nothing if not emotional.)

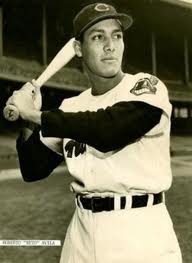

The ‘54 Tribe were a tight-knight squad who knew they were good. One of the leaders of the team was the veteran second baseman. The AL batting champion, Bobby Avila.

Avila, the Indians’ Man of the Year in 1954, hit .341 on the season. He flirted with .400 until a slide by Hank Bauer of the Yankees resulted in a broken thumb. His average dipped close to .300 before rebounding. The second-place hitter was Minnie Minoso, at .320. Ted Williams hit .345 that season- so where did he rank? Williams, plagued by the injury bug, didn’t qualify for the batting title since he was only credited with 386 at-bats (although he did walk about 150 times - nowadays, the walks would count, as ‘plate appearances’).

Avila, the Indians’ Man of the Year in 1954, hit .341 on the season. He flirted with .400 until a slide by Hank Bauer of the Yankees resulted in a broken thumb. His average dipped close to .300 before rebounding. The second-place hitter was Minnie Minoso, at .320. Ted Williams hit .345 that season- so where did he rank? Williams, plagued by the injury bug, didn’t qualify for the batting title since he was only credited with 386 at-bats (although he did walk about 150 times - nowadays, the walks would count, as ‘plate appearances’).

Avila, whose first name was actually Roberto and who was known as Beto in his native Mexico, was on the leading edge of the wave of Latin players entering the major leagues in the 1940s. His father was a successful lawyer and expected Bobby to follow in his footsteps. But the younger Avila loved baseball, and began playing in the Mexican League in 1943 at age 19. Over the next two seasons, Bobby blossomed as a ballplayer. Then, in 1946, the caliber of player in the Mexican League was suddenly much greater due to the efforts of Jorge Pasquel.

Pasquel, the son of a shipping magnate, was the owner of the Mexican League. Several years earlier, he had lured many players from the Negro Leagues (indirectly exerting pressure on Major League Baseball to integrate). And now he was bringing major league (white) players from north of the border into his league.

Bobby Avila continued to shine in the Mexican League, and major league scouts noticed. The Boston Braves came knocking. Branch Rickey and Leo Durocher of the Brooklyn Dodgers offered Avila a contract for $10,000. The Washington Senators showed interest. The Dodgers seem to have been close to signing him, but then Durocher was suspended from Baseball. Around the same time, Rickey signed his second baseman of the future. Number 42, Jackie Robinson.

Leo The Lip was both admired and hated for his fiery personality and his lifestyle. His suspension as Dodger manager in 1947, influenced by the political maneuverings of others in authority, was largely due to:

1) his ties with known gambling figures,

2) his feud with Yankee part-owner Larry MacPhail, and

3) the accusations of his wife’s ex-husband that Durocher stole her from him while posing as a friend.

Bobby Aliva played one more season in the Mexican League, winning the batting title. Indians’ super scout Cy Slapnicka offered him $17,500. Avila signed.

Slapnicka, known for his signing of Bob Feller to a professional contract, was a big reason the Indians won pennants in 1948 and 1954. Other notable Indians he signed throughout the years included Hal Trosky, Herb Score and Roger Maris.

By 1948, at age 25, Bobby Avila was on the Indians’ roster. He reported to the minor league team in Baltimore, but rules determined that as a ‘bonus baby’ he was required to stick with the Indians. He backed up Joe Gordon, who was the established Indians second baseman. Gordon, an acrobatic defender who hit with power, was sidelined due to injury the next season, and Avila began his eight-year run as the Tribe’s second baseman of the 1950s. He was the leadoff hitter, but Lopez considered him a more ideal fit in the two-hole due to his ability to hit-and-run. When the Indians added right fielder Al Smith as the new leadoff hitter, the lineup was set. Smith was big, fast, and had a nice arm (Smith was one of three black ballplayers on the mid-’50s team, along with Doby and Pope). More than once, Smith scored all the way from first base on an Avila bunt. (Smith and Avila are in the photo at right).

Avila’s style of play was aggressive and daring, whether in the field, at the plate or on the base paths. Many credited his background in soccer as a reason his footwork was such a strength. He was adept at kicking the ball out of the glove of an infielder- several opponents looked upon this as a breach of the unwritten rules of baseball, and they slid extra hard into Avila at second base. He shrugged that off as part of the game.

Besides being an expert bunter, Avila was a pull hitter who was known to have some pop in his bat as well. He hit 15 home runs in 1954, and nearly every one was said to have come in a clutch situation. He was a fastball hitter, and breaking balls gave him trouble. Some of his success can be traced to the ahead-of-its-time film study Tribe GM Hank Greenberg helped him with; they worked together to level out Avila’s uppercut swing.

Assimilating into the culture of the United States was not as simple for Bobby Avila as it seems to be for foreign players today. There were no translators or advisors available. Indians Traveling Secretary Spud Goldstein came up with the idea to room Avila with Hank Majeski, and the two players hit it off well. Mike Garcia was a second-generation U.S. citizen from Mexican heritage; he laughed about how he couldn’t rid himself from the presence of Avila, but ‘The Big Bear” happily helped the young player get acclimated. One must also remember: Bobby Avila was a star in Mexico before coming to the major leagues. Going from being a renowned athlete in his home country to an unknown in the U.S. was another adjustment he needed to make.

Avila had reached the highest level of celebrity in Mexico, rivaling boxer/actor Raton Macias (who captured the imagination of his country with the help of its fledgling television industry in the 1950s) and General Humberto Mariles, a fiery, outspoken, bald show jumper (who counted Olympic gold among a lifetime of achievement).

fledgling television industry in the 1950s) and General Humberto Mariles, a fiery, outspoken, bald show jumper (who counted Olympic gold among a lifetime of achievement).

Avila was known to send money to several family members on a regular basis. He later noted he was proud of giving his best at all times, and never taking his opportunities for granted. For example, he said he never played while hung over.

Avila’s was an avid movie-goer. Dressed in a fine suit (purchased in Mexico due to the relatively low cost), he would dine out and enjoy a cigar before heading off to a theater. (The cigar smoking originated as sort of a hazing moment when a veteran big leaguer advised he’d need to do that to fit in. It wasn’t true, but Avila enjoyed them.)

Bobby Avila played in the American League All-Star game in 1952, 1954 (held in Cleveland) and 1955. He was dealt by infamous Indians General Manager Frank “Trader” Lane after the 1958 season, on the same day Lane traded Vic Wertz in a deal which landed Jimmy Piersall from Boston Red Sox. Avila was replaced as the Indians’ second baseman in 1959 by an aging Billy Martin.

Avila bounced around among a few teams in 1959. He was 35 years old. The Boston Braves’ contract offer for 1960 represented a $10,000 pay cut, so Avila went back to Mexico and played for a bit (he’d owned and managed a team in previous off seasons- but unexpected hassles such as players in the dugout asking for more money kept that level of involvement from being fun. He did eventually become president of the league). He later said that he could have played another five years in the big leagues.

After he was through playing, Avila became a successful politician. He credited learning how to deal with people in baseball as having helped him in politics. He was a gracious, informal ambassador of baseball - and of Mexico - throughout his life, until he succumbed to a long bout with diabetes in 2004 at age 78.

Thank you for reading. Next week: Blast From The Past: John Rocker