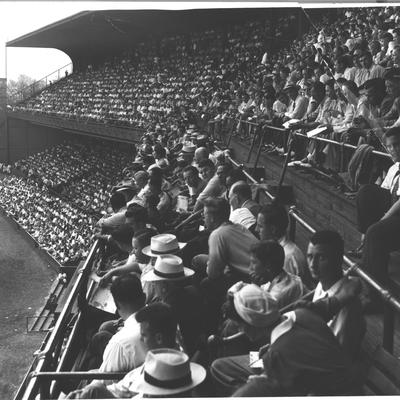

Bravo to those involved in the current initiative to rebuild League Park. This wasn’t some temporary landing spot for the Cleveland Indians; it was local big-league baseball’s home for 55 seasons. It also housed the champion Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro leagues during an era when the Indians, Browns and Barons were also winning titles, in the 1940s. A restored ballpark could suitably honor the teams who represented Cleveland through eras such as the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression. It would highlight the connection our relatives from long ago had with key milestones in baseball history. The clincher is that it could serve as a nucleus of activity that can attract attention, people and money to a run-down area of town.

Bravo to those involved in the current initiative to rebuild League Park. This wasn’t some temporary landing spot for the Cleveland Indians; it was local big-league baseball’s home for 55 seasons. It also housed the champion Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro leagues during an era when the Indians, Browns and Barons were also winning titles, in the 1940s. A restored ballpark could suitably honor the teams who represented Cleveland through eras such as the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression. It would highlight the connection our relatives from long ago had with key milestones in baseball history. The clincher is that it could serve as a nucleus of activity that can attract attention, people and money to a run-down area of town.

A Google search for League Park results in some nice options to view local news footage of the restoration effort. I also applaud the politicians who have hopped onto  the bandwagon. Sure, it is an easy attention grab- who cares, if it serves the interests of a good cause? I do feel compelled,

the bandwagon. Sure, it is an easy attention grab- who cares, if it serves the interests of a good cause? I do feel compelled, however, to keep it real about Dennis Kucinich’s support. I clearly remember that guy’s act when Gateway was in its embryonic stage, in the late 1980s. That was the project that would feature Jacobs Field and Gund Arena. It revitalized a sector of downtown that previously featured empty buildings, crumbling asphalt, and rust. Dennis Kucinich publicly campaigned against it.

however, to keep it real about Dennis Kucinich’s support. I clearly remember that guy’s act when Gateway was in its embryonic stage, in the late 1980s. That was the project that would feature Jacobs Field and Gund Arena. It revitalized a sector of downtown that previously featured empty buildings, crumbling asphalt, and rust. Dennis Kucinich publicly campaigned against it.

The ballpark was called National League Park when it opened in 1891. It was the latest in a succession of fields and parks that had been home to professional Cleveland baseball teams dating back to 1869. The location was selected by the then-named Cleveland Spiders’ owner Frank DeHaas Robison. Two of Robison’s trolley lines intersected at East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue. As the ballpark name made clear, the team was a member of the National League. By 1900, Cleveland became a charter member of the new American League (and the ‘National’ portion of the ballpark name was dropped). The team was variously named, or known as, the Blues, Bluebirds, and Bronchos, until team owner Charles Somers spearheaded a newspaper contest to name the team. The winning entry was “Naps”, in honor of local star Napoleon Lajoie. Another contest was held in 1915; the winner was the ‘Indians’. And here we are.

Conventional wisdom holds that the fan who submitted the name ‘Indians’ selected the name in honor of Native American Louis Sockalexis- the first ‘Indian’ to play in the major leagues. Some historians disagree.

historians disagree.

The team had its professional stadium, and its brand new team nickname… and in 1916, the stadium’s name changed. James “Sunny Jim” Dunn purchased the team and the ballpark name was now “Dunn Field”.

Nowadays they’d probably have called it something like, “League Park at Dunn Field”. Of course, our beloved Cleveland forefathers had a way of creatively naming city landmarks. From League Park, to Cleveland Arena, to Cleveland Municipal Stadium. To Terminal Tower…

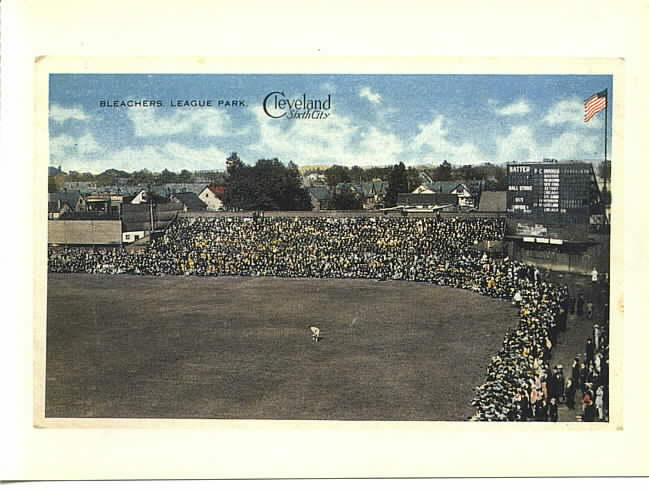

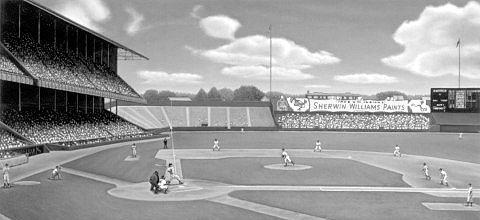

The ballpark was nestled tightly in its residential neighborhood. It was in the shape of a rectangle. Left field was 385 feet from home plate, with bleachers wrapped around the foul pole. Dead center field was a full 460 feet away. The right field fence crowded Lexington Avenue, and was 60 feet high (as a comparison, Fenway Park’s Green Monster is 37 feet high). The right field foul pole was only 290 feet away. The park held 27,000 after a series of improvements over the years, and was (in Tom Hamilton parlance) a two-deck affair.

(as a comparison, Fenway Park’s Green Monster is 37 feet high). The right field foul pole was only 290 feet away. The park held 27,000 after a series of improvements over the years, and was (in Tom Hamilton parlance) a two-deck affair.

Some notable events in baseball history that happened at League Park include Ohioan Cy Young pitching there for the home team in the ballpark's inaugural game, Bob Feller's career debut in 1936, Babe Ruth's 500th career home run, and Joe DiMaggio's (photo) hitting streak extending to a record 56 games and then getting stopped the next day.

Dunn’s widow sold the team and the ballpark to Alva Bradley in 1927. The name “League Park” returned.

Which means that when Cleveland hosted the World Series in 1920, it was technically held at Dunn Field. And there wasn’t universal agreement on the name of the championship series. Prior to 1920, most 1900s references were variations of “World’s Championship” and “World’s Series”. Cleveland’s game programs for 1920’s series referred to the “World Series”, and this name began to become the standard by the mid 1920s.

By around 1920, Baseball had arrived at multiple crossroads in its history. Allegations that the Chicago White Sox threw the 1919 “World’s Series” to the Cincinnati Reds hung like a dark cloud over the entire season. With only a few regular season games remaining, Judge “Kennesaw Mountain” Landis (newly installed as Baseball’s first commissioner) suspended eight White Sox players suspected of taking money from a noted Chicago gambler in return for not playing to win. A very tight pennant race broke Cleveland’s way at the very end, and the Indians were in the Series. The gambling scandal stretched into 1921, and threatened to bring the professional game down.

players suspected of taking money from a noted Chicago gambler in return for not playing to win. A very tight pennant race broke Cleveland’s way at the very end, and the Indians were in the Series. The gambling scandal stretched into 1921, and threatened to bring the professional game down.

By this time, the New York Yankees- a franchise that had never enjoyed success- had suffered in comparison to the other New York teams, the Giants and the Dodgers. They had just acquired Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox. This brings us to the other crossroads for Baseball: the end of the dead-ball era, and the dawning of the live-ball era. Ruth made the home run popular; he gets some credit for a change in hitters to more of a free-swinging philosophy. (Top home run hitters of the day often hit in the low teens; Ruth hit 54 in 1920- along with his .376 batting average.) Other reasons given for the dawning of the live-ball era include an alleged ‘livelier’ ball, the outlawing of trick pitches like the spitball, a shortening of the distances of home run fences in some ballparks, and rules changes like allowing fly balls that hook around foul poles to be called home runs, even when they land in foul territory after passing the pole.

Another noted reason for the live-ball era- and one that generally is not disputed- is the change of Baseball toward using more balls per game. This resulted in clean, white, easily seen baseballs being used throughout the game. This was the direct result of the fatal beaning of Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman- in 1920. An account of the beaning by the Yankees’ Carl Mays can be read here. The Indians enjoyed a large early lead in the pennant race. The death of Chapman sent the team into a tailspin, and the lead was squandered. Then came the commissioner’s suspensions of the eight White Sox and the Indians held on to win the pennant.

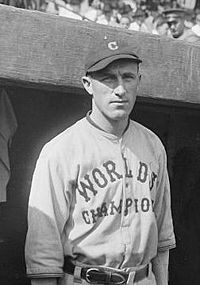

The top star on the Indians was player/manager Tris Speaker. He’d already led the Boston Red Sox to two World’s Championships, and had been reluctant to join the uncompetitive Indians when they’d bought his contract. He’d had a dispute with Red Sox president J.J.

The top star on the Indians was player/manager Tris Speaker. He’d already led the Boston Red Sox to two World’s Championships, and had been reluctant to join the uncompetitive Indians when they’d bought his contract. He’d had a dispute with Red Sox president J.J. Lannin, who wanted to cut his pay. With the help of the American League president, Speaker received some of the money the Indians had agreed to pay Lannin for the player. When he first arrived, he served as the unofficial assistant manager, and in 1920 officially managed Cleveland to the pennant. Speaker played center field, and positioned himself shallow enough to occasionally act as a fifth infielder. He was liable to cover second on a bunt, allowing the shortstop (Chapman, mostly) to cover third when the third baseman charged the plate. On occasion, Speaker took the relay on a double play, and at times was known to take a pickoff throw from the catcher. Of course, he was generally able to run out toward the fence and catch up to balls as needed as well. Speaker was perhaps the preeminent outfielder in baseball history, pre-Ruth.

Lannin, who wanted to cut his pay. With the help of the American League president, Speaker received some of the money the Indians had agreed to pay Lannin for the player. When he first arrived, he served as the unofficial assistant manager, and in 1920 officially managed Cleveland to the pennant. Speaker played center field, and positioned himself shallow enough to occasionally act as a fifth infielder. He was liable to cover second on a bunt, allowing the shortstop (Chapman, mostly) to cover third when the third baseman charged the plate. On occasion, Speaker took the relay on a double play, and at times was known to take a pickoff throw from the catcher. Of course, he was generally able to run out toward the fence and catch up to balls as needed as well. Speaker was perhaps the preeminent outfielder in baseball history, pre-Ruth.

Joe Sewell was the replacement at shortstop for Ray Chapman. He performed at a high level once he reached Cleveland. Like Speaker, Sewell would eventually make the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The starting pitching staff of the Indians was a team strength. Jim Bagby Sr. was the 31 game winner. Stan Coveleski (photo) and Ray Caldwell each won at least 20.

The starting pitching staff of the Indians was a team strength. Jim Bagby Sr. was the 31 game winner. Stan Coveleski (photo) and Ray Caldwell each won at least 20.

So the Cleveland Indians won the right to face Brooklyn in the Series. The Dodgers also were known at the time as the Robins, in honor of manager Wilbert Robinson. In 1920, the Series was best-of-nine; this was a bit of an aberration. Best-of-nine series had been held a few times prior, but best-of-seven was the rule.

Coveleski won three of the five games Cleveland needed in the Series. He and the Robins’ Burleigh Grimes were the two noted spitballers to appear in the matchup; they had been among those who were active when the spitball was outlawed and thus were ‘grandfathered’.

With the Series tied at two games apiece, the pivotal fifth game proved to be the most memorable. Held at Dunn Field, the Indians boasted a grand slam in the first inning by Elmer Smith, a home run by the pitcher Bagby (both firsts in Series history), and the first and only unassisted triple play ever in the World Series.

The Indians were up on Brooklyn by a bunch in that fifth game, but there was suddenly some tension developing at Dunn Field- two Robins hitters reached base with no outs. Clarence Mitchell came up to pinch-hit. He was a pitcher, but also an accomplished hitter. He ended up 6 for 16 in the Series. Robinson put the hit-and-run on, which sent second baseman Billy Wambsganss toward the bag. Mitchell hit a hard liner to the right of second base. Wambsganss reached out to grab it, and took the remaining couple steps to toe second. He turned and trotted to tag the runner who’d been on first- triple play. Wambsganss (who was known as Wamby as that is how his name was typed in newspaper box scores) later said that he’d seen that play before, so it did not take him by surprise. But the home fans were momentarily silent. As Wambsganss trotted off the field and into the dugout, the ballpark exploded into celebration.

The Indians were up on Brooklyn by a bunch in that fifth game, but there was suddenly some tension developing at Dunn Field- two Robins hitters reached base with no outs. Clarence Mitchell came up to pinch-hit. He was a pitcher, but also an accomplished hitter. He ended up 6 for 16 in the Series. Robinson put the hit-and-run on, which sent second baseman Billy Wambsganss toward the bag. Mitchell hit a hard liner to the right of second base. Wambsganss reached out to grab it, and took the remaining couple steps to toe second. He turned and trotted to tag the runner who’d been on first- triple play. Wambsganss (who was known as Wamby as that is how his name was typed in newspaper box scores) later said that he’d seen that play before, so it did not take him by surprise. But the home fans were momentarily silent. As Wambsganss trotted off the field and into the dugout, the ballpark exploded into celebration.

Cleveland took the Series in seven games.

Baseball America poses an interesting question: if there had been a World Series Most Valuable Player Award in 1920, who would have won? Coveleski won three games. Bagby had an ERA under two and hit a home run in the fifth game. Elmer Smith was a hitting hero; Wambsganss scored the most runs and had the unassisted triple play. I’d take Coveleski. Which reminds me- any time someone says a pitcher cannot be a season MVP because he can already win a Cy Young Award, I say bullcrap. If he is most valuable, why should the award be saved for a hitter? If it makes fans happy, introduce an award for hitters that equals the Cy Young for pitchers (You say that the MVP award isn’t always given to the most valuable player, but rather to a player with great stats? Yeah, good point.)

Deciding which Cleveland ballplayer deserves the World Series MVP award? Good stuff. We need some more of that around here.

And we also need to remember our past glory. Rebuild League Park.

Go get em, Dennis.

Thank you for reading. Type 'league park cleveland' into a YouTube search. Enjoy!