Kevin Mackey kneaded his hands together obsessively, feeling sweat begin to pinprick into tiny beads across his forehead as the pounding of his pulse in his ears sounded like waves along Lake Erie's rocky shore.

Kevin Mackey kneaded his hands together obsessively, feeling sweat begin to pinprick into tiny beads across his forehead as the pounding of his pulse in his ears sounded like waves along Lake Erie's rocky shore.

The room he sat in on this Sunday evening, filled with such young, vibrant energy just a few minutes before, had drawn eerily silent once six o’clock arrived. Everyone watched morbidly over the next few minutes as the names of dozens of other schools popped up on the television screen. But not theirs.

Twenty-four hours before, the 1985-86 Cleveland State Vikings had completed their mission, doing everything in their power to earn their first invitation to the NCAA tournament. With a gritty win over Eastern Illinois witnessed by less than 2,800 spectators in Springfield, Missouri, the Vikings had captured their first Association of Mid-Continent Universities (affectionately known as the AMCU-8) tournament championship with their 12th straight victory, bringing their overall record to an impressive 27-3.

But now, with the NCAA tournament in just its second year as a 64-team field and the qualification process still evolving, Cleveland State was at the mercy of the selection committee. And as the names scrolled across the screen on the tiny television in this cramped room in the CSU Physical Education Building, it looked more and more like the Vikings were going to get passed over – just as they had the year before by both the NCAA and NIT committees despite 21 victories and their first regular-season AMCU-8 crown.

Now, as the 1986 tournament bracket began to fill in, the Vikes’ third-year head coach was getting a bad feeling. Ohio Valley Conference champ Akron, whom Cleveland State had defeated by 12, was announced. Then came DePaul, whom the Vikings had trounced by 15 at the Rosemont Horizon in January. Of course, Big Ten champ Michigan was in as a No. 2 seed, and Mackey wondered if anyone on the selection committee knew that his Vikings had given the Wolverines a good half of basketball back in December, trailing by only two at the intermission.

As each school’s name was announced and the number of spots left on the bracket dwindled, it just didn’t feel like it was going to happen.

The top half of the fourth and final bracket filled in – still no Cleveland State. Mackey knew, even if his players didn’t, that if they weren’t invited now, they never would be. There was nothing more he could do, no better team he could assemble here, none that was better qualified to earn a tournament spot. It looked as though once again these talented but generally unrefined young athletes, most from inner-city neighborhoods, would be passed over. They would never have another shot to show how good they could be.

Finally, in the second-to-last pairing, in a bolt of green-and-gold lightning, there it was:

14 Cleveland St.

The room erupted. Players and coaches leapt into each other’s arms. Some players openly wept in relief. This time, they hadn’t been passed over. For the first time in school history, they were going to the dance.

Off-Broadway Guys

It would be oversimplifying things to say this was the moment Cleveland realized its only major university had a basketball program. CSU first fielded a team in 1929, but it was probably best known for once losing 30 straight games between 1959 and 1961. Aside from a handful of decent squads in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the program had been abysmal. When Mackey took over in 1983 after serving as a hard-working assistant at Boston College, the Vikings were coming off their fourth 20-loss season in the previous 14 years.

Once Mackey arrived on Euclid Avenue, there was an immediate impact. The Vikes went from eight wins to 14 in Mackey’s first season, then to 21 in his second along with the regular-season AMCU-8 crown – the program’s first-ever conference title.

These teams had been built with spare parts off the scrapheap that the bigger, more established programs didn’t want – players who were deemed to be a few inches too short or a step too slow. Mackey himself described his players as “off-Broadway guys; players who watch every game on the tubes and eat their hearts out waiting for their chance.”

What he wound up with was a menagerie of colorful characters whose nicknames defined their offbeat personalities and playing styles: Vinny Vandalism. The Gigolo. Iceberg Slim. The Identified Flying Object. Black Rambo. And the Mouse.

On this glorious Sunday evening, these Vikings had reached the promised land. They had waited for their chance, and now they had it.

As the cacophony quieted in the aftermath of the news that had just crackled over the television, everyone looked to Mackey, not quite sure what to do next. The fiery little coach’s leadership and determination had taken them this far, now it had to take them a little further.

Knowing what was expected of him, Mackey asked himself what the first step should be. It didn’t take long.

“Hey,” the coach wondered aloud, “who do we play?”

The players and coaches alike looked at each other dumbly. Little details like that hadn’t seemed important.

Mackey had an assistant phone the Plain Dealer to find out.

Run and Stun

It would be Indiana, the third seed in the East Region and ranked 16th in the final AP poll. It was a legendary program five years removed from its fourth national championship and now defined by clean-cut, sharp-shooting guard Steve Alford and brilliant, volcanic head coach Bobby Knight.

Mackey, a short, pudgy Irishman who would look like a cartoon character compared to the larger-than-life Knight, admitted he’d never met the iconic coach, but he’d read all his books.

To anyone else who’d read Knight’s books and revered them as basketball gospel, the upcoming matchup looked hopeless for the underdog Vikings. Indiana was one of the giants of college basketball and Knight had virtually invented the modern game. Cleveland State was...well, Cleveland State.

But Mackey knew better. He respected Knight and all the other successful coaches who served as anchors of the game, as well as the rock-solid philosophies they indoctrinated in their players. But Mackey’s Vikings played an altogether different brand of basketball.

They called it “run and stun,” and it left an indelible mark on all who saw it. The Plain Dealer’s Bill Livingston likened witnessing a Cleveland State game to watching “inner-city scramblers come at opponents like stinging squadrons of ants from an overturned hill.”

It was a method of madness still three to four years away from gaining a foothold in the college game: up-tempo the entire game on both sides of the ball, defined by a swarming full-court press, an offense perpetually running a fast break, and a 10-man rotation that wore teams down.

The Vikings had led the nation in scoring over the course of the 1985-86 season, averaging more than 90 points per night, and had outscored their opponents by just under 21 points per game. They’d scored more than 100 points 12 times and more than 90 on 18 occasions.

While most coaches looked at an opponent’s field goal percentage as an effective benchmark of how well their own defense had played, Mackey didn’t really care how well an opponent shot. He was more than willing to give up a few easy baskets in order for the Vikings to get a few more. He focused his attention on a handful of other statistics, primarily turnovers.

He was certain Indiana, like most teams across the country, had never seen a pressure attack like Cleveland State’s.

“This is a milestone,” senior CSU center Bob Crawford admitted that Sunday night. “But getting into the tournament is not enough. We want to win. Indiana can be beaten.”

Mackey didn’t disagree, though he put it in more coy terms. “When I was a kid,” he said with his thick Boston accent, “I read Cinderella just like everybody else.”

A Glass Slipper in Green and Gold

In the minutes before the opening tip at the Carrier Dome in Syracuse, New York, the following Friday afternoon, Mackey engaged in some playful psychological warfare. As he approached Knight for a pre-game handshake, he sheepishly requested, “Go easy on us, big guy.”

But both coaches knew Mackey wasn’t serious. They both understood that while Indiana clearly had more talented players, this was going to be a hard-fought game. It took less than two minutes for everyone in the Carrier Dome to realize it, too.

Before most fans had settled into their seats, Cleveland State had collected a pair of steals and took a quick 6-2 lead. The tone was set, and Mackey was proven right. In all its games against heralded, much more talented teams in the Big Ten and beyond, Indiana hadn’t seen anything like Cleveland State’s non-stop pressure defense. The Hoosiers would commit 10 turnovers in the first 20 minutes as the Vikings took a 45-41 lead to the half. By now, the majority of the 16,000-plus packed into the arena were rooting for the little guys in green.

Mackey’s mites proved the first half was no fluke, scoring the first six points of the second half to march to a 10-point advantage. From there, they simply hung on, countering every Indiana punch with one of their own. When the Hoosiers cut the margin to four with just over three minutes to play, the Vikings quickly stretched it back to double digits.

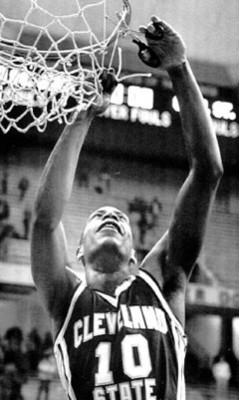

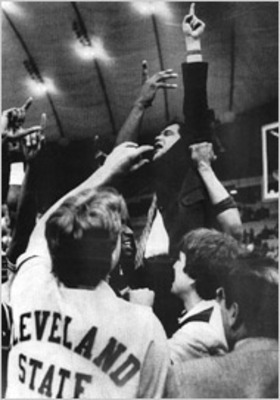

And when John Adams High School grad Clinton Smith, who’d come to CSU by way of Ohio State and Arizona Central Junior College, hit a pair of free throws to push the lead back to six with 21 seconds left (and the three-point shot still a year away in college basketball), the Vikes were in the clear. When the buzzer sounded, his players hoisted the squat Mackey up onto their shoulders and carried him off the court.

The final was 83-79, marking the first time Bobby Knight had ever been defeated in the first round of an NCAA tournament and the first time in the history of the tourney a 14 seed had defeated a No. 3.

Back in Cleveland, jubilant CSU students exploded out onto Euclid Avenue to celebrate. Guys ripped their shirts off despite the cold and ran around the concrete campus like jovial lunatics as toilet paper streamed down from windows of the surrounding buildings. Appreciating the significance of the moment, nearby police officers simply smiled and shook hands with the celebrants. Drivers snarled in the Friday rush-hour traffic along Euclid honked their horns and waved.

The party eventually flowed to the Rascal House Saloon for a night of revelry as glowing CSU students and alums alike felt as if their basketball team had just put their school – and by extension themselves – on the map of the world.

“Now they know the AMCU-8 isn’t motor oil or something,” Mackey quipped in the press conference afterward.

But that wasn’t all they knew. Like the rest of the sports world, they realized that Cinderella had just moved to Cleveland.

Locomotive of Destiny

“We got beat by a pretty damn good basketball team,” a somber Bobby Knight said after the game. “They will be a tough team for anybody to beat. These kids can really play.”

While it may have been the surprise of the tournament, those who understood basketball and assessed Cleveland State’s arsenal knew this was no miracle. Syracuse coach Jim Boeheim said not only was he not surprised, but he wouldn’t call it an upset. North Carolina State’s Jim Valvano admitted he’d hate to have to play Cleveland State.

That unenviable task would fall to St. Joseph’s, who’d barely squeaked past No. 11 Richmond in the first round and now would have to try to stop a locomotive called destiny barreling toward them at full speed.

And sure enough, that Sunday afternoon, on the third anniversary of the day Mackey was hired as CSU coach, the Vikings overcame their worst first half of the season to pull away in the second to win, 75-69. Leading the way was freshman guard Kenny “Mouse” McFadden, a scrappy playground legend from New York City who hadn’t even played high school basketball but scored 23 points against St. Joe’s in front of 21,000 enraptured fans.

Cleveland State University was headed to the Sweet Sixteen.

The week that followed was like a dream as the Vikings became not only the talk of Cleveland, but of the nation. The CSU bookstore sold out of most of its apparel and merchandise. Local and national media descended onto campus to get the lowdown on these lovable underdogs. Led by its Irish coach, the team returned home on St. Patrick’s Day as heroes and, amidst a veritable circus of distraction, prepared for their next challenge: seventh-seeded Navy, led by center David Robinson and fresh off an upset of No. 2-seed Syracuse. The New York Post billed the Viking/Midshipmen clash as “the short hairs against the short hares.”

When the Vikings left for the regionals in East Rutherford, New Jersey, on Wednesday afternoon, they were sent off with an impromptu pep rally attended by more than 300 students and Mayor George Voinovich.

That Friday night, as the first official day of spring came to a close and snow flurries swirled outside, Cleveland State students packed into the Rascal House once again to watch their Vikings – who’d started this remarkable journey four months before against tiny Clarion University – on national television. In the second half, the Rascal House fanatics were joined by Ohio Governor Richard Celeste, just beginning his re-election campaign. As the night wore on and the wind whipped the snow into drifts outside, Celeste and the CSU crazies witnessed a classic.

Again the Vikings started sluggishly and trailed by nine at the half. As always, they persevered, chipped away, and eventually came all the way back to take a 56-55 lead with 8:34 left, then stretched it to five points at the seven-minute mark. The Rascal House patrons, by now quite accustomed to the unlikely, roared in celebration, if not surprise. By God, the Vikings were going to do it again.

From that point on, it was nip and tuck. Robinson was nearly unstoppable, scoring 15 of Navy’s last 19 points, but Cleveland State countered every bucket. And when Clinton Smith broke free for a layup with 27 seconds remaining, the Vikings had a 70-69 lead and were one defensive stop away from the Elite Eight.

With 11 seconds left, a lob pass inside to Robinson was knocked away. Cleveland State’s Paul Stewart snatched the ball and apparent victory. But in the next split-second, Navy’s Vernon Butler reached in and got his hands on the ball, forcing a tie-up and a jump-ball whistle with eight seconds remaining. The possession arrow favored Navy, so the Midshipmen would have one last chance.

To this day, Viking fans contend Butler fouled Stewart. Adding an even more haunting shroud over the play, two months later, the 19-year-old Stewart died of heart failure during a pickup game.

On the ensuing in-bound play, Robinson caught a lob pass and gracefully banked a five-foot shot off the glass and through the hoop to give Navy the lead with five seconds remaining.

The Vikes had one last chance. Smith took the in-bound pass and sprinted upcourt. Not able to see the Mouse open on the wing as he crossed the timeline, Smith instead stopped and launched a 25-foot shot. Time seemed to stand still inside the arena as the ball sailed perfectly on course toward the basket – carrying the potential of one more miracle in this season of perpetual hope.

Instead, the ball hit the back of the rim and bounced away as the buzzer sounded. The clock had struck midnight at Cleveland’s trip to the ball.

Silver Anniversary Echoes

Back at the Rascal House, the crowd quieted for a moment in disappointment as Smith’s shot fell away. But in a matter of seconds, a defiant, triumphant chant began to build.

“CSU! CSU! CSU!”

Twenty-five years later, those cheers from that cold Friday night still echo down the canyon of Euclid Avenue.

The CSU program, like Cleveland itself, has had ebbs and flows and, in general, has suffered greatly over the last 25 years. While Cleveland State remained a force in the following few seasons, they never could quite recapture the rapture of 1986.

The next two campaigns brought 25 and 22 wins and a pair of NIT berths, including a trip to Columbus to meet Ohio State in the second round in March of 1988. But earlier that season, the NCAA had slapped Cleveland State with three years’ probation to begin the next year along with a two-year ban from postseason play for improperly recruiting foreign players.

The bright promise of the program then utterly collapsed in the summer of 1990 when Mackey was arrested for drunk driving after leaving a crackhouse and admitted he was addicted to cocaine. He was fired, never to return to college basketball. After successful rehabilitation, he bounced around coaching between the United States Basketball League and the International Basketball Association and eventually wound up serving as a scout for the Indiana Pacers.

After Mackey’s fall from grace, the program was never quite the same. CSU returned to long stretches of mediocrity and anonymity, even after hiring legendary former Villanova coach Rollie Massimino in 1996. After losing 20 games or more three times in five seasons between 2003 and 2007, the Vikings finally returned to glory.

Under new coach Gary Waters, they won 21 games and earned an NIT invitation in 2008, then won 26 the following year, capped by an upset of Butler in the Horizon League title game to get back to the NCAA tournament for the first time since ’86. And just like Mackey’s boys, these Vikings pulled off an upset, clobbering fourth-seeded seeded Wake Forest in the first round before falling to Arizona in the second.

While similar, things just weren’t the same. That 1985-86 Cleveland State team still endures as one of the greatest Cinderella stories in NCAA tournament history, and Mackey’s overachieving Vikings have etched themselves in Cleveland lore as arguably the best basketball story Northeast Ohio fans have ever witnessed.

It’s been a quarter-century since the Vikings lit up Euclid Avenue, and in the interim, Cleveland’s teams have regularly frustrated and heartbroken their fans. But for 12 unforgettable days in what would become a magical sports year along Lake Erie’s shore, a group of athletes nobody else wanted finally found a home – and showed Cleveland just how mad March could be.