Click here for Part I

Click here for Part IClick here for Part II

While the Browns were acting as the Broncos' personal punching bag, the Cavaliers made a phoenix-like rise from Ted Stepien's ashes. With Mark Price at point guard and the gift first-round pick turning into Brad Daugherty, the Cavs became a real power in the NBA's Eastern Conference. Magic Johnson dubbed them "the team of the nineties." Hall of Fame coach Lenny Wilkens provided quiet strength to an efficient, beautiful team that put the days of Keith Lee, John Bagley, and "Dinner Bell Mel" Turpin behind it. They even won some playoff games.

They did not, however, beat Michael Jordan. Ironically, "The Shot" was not even the closest the Cavs got to the NBA Finals, but it is the single most nauseatingly-replayed professional basketball play of all time. Cleveland fans do not like montages and generally avoid ESPN Classic. Daugherty got hurt, Larry Nance got old, Mark Price lost a step, and the Cavaliers became the Cavaliers again, with a brief stop at The Little Engine That Could But Was So Boring In Doing So That Even Mike Fratello Felt Guilty.

Meanwhile, in 1990, I bet my college roommate's fiancé that the Cleveland Indians would finish with a better record than her beloved Atlanta Braves. If you are 20 or younger, it may be hard to imagine the mighty juggernaut Braves being anything but Division Champions and a perennial playoff team, but you'll just have to take my word for it: this was a pretty safe bet. The Indians were lousy, to be sure, but the Braves were simply atrocious. I even gave her extra handicaps, like giving her bonus wins if the entire Atlanta staff finished with as many saves as the Indians' closer, Doug Jones. I won the bet and still own the 1954 replica Indians hat they mailed me. The next year, Atlanta began its string of great success, while the Indians remained mired in their intrinsic Indianosity. There is something to be said for superior timing.

Doug Jones was my favorite Cleveland Indian. A journeyman pitcher who had failed as a starter in Milwaukee, he became the Indians closer after he stopped throwing any breaking pitches. He was fed up one day and threw nothing but fastballs, but varied his grip and delivery so that no two pitches came at the same speed. Eventually he refined this technique into the variety of changeups he would parlay into a long, successful career: he was compared to the famous Stu Miller, who was known for two things. Pitching in San Francisco's Candlestick Park, Miller was once blown off the mound by a gust of wind in the middle of his windup. And a teammate once described Miller's repertoire as "slow, slower, and slowest." Doug Jones made Stu Miller look like Nolan Ryan. He started with "slower," skipped "slowest," and proceeded to "backwards." He was listed at 6'2" and 210 pounds, but looked easily 20 pounds heavier, so that his uniform looked more like pajamas than a professional athlete's gear. He also sported a moustache that Wilford Brimley would have committed larceny for. He had nothing: no athleticism, no "stuff," and he was great. He also stuck out like a sore thumb on an Indians team largely devoid of greatness, but he was great nonetheless. As a Cleveland fan, I tended to latch onto small victories: Sutcliffe leads the league in strikeouts! Jones leads the league in saves! Mike Jeffcoat leads the league in appearances! (I could be pretty desperate for something to latch onto.) Naturally, Jones was not an Indian for long.

The Indians changed everything in the early mid-nineties by acquiring some young players through trades and others through the draft, then adding some key veterans, especially to the pitching staff. In 1994, the team was actually winning games at a good clip. They had a legitimate shot at making the playoffs, just a few games behind the White Sox in the new Central Division, when the players went on strike. To no Cleveland fan's surprise, the season did not resume. The Indians would not be in the playoffs, as usual, just not for the usual reason.

However, not even fate could keep the Indians from making the playoffs the next season. Albert Belle hit 50 doubles AND 50 home runs in a shortened 144-game season. The Indians won 100 games. Kenny Lofton scored from second base on a Randy Johnson wild pitch. And the Indians, the CLEVELAND INDIANS, went to the World Series.

Where they lost to the Atlanta Braves. But at least they'd done something no Cleveland team had done since I was four months old: they'd played in the championship. It was almost like erasing The Cleveland Experience. Almost.

There are several settings in "Backyard Baseball." One changes the difficulty level from Easy to Medium to Hard, and another allows you to see the exact location of the pitch or not. When he began playing the game, Chris prudently initialized the settings to Easy and exact: this makes sense for someone learning to play a new game. In Easy mode, the opponent's fielders are pretty bad, and they hold the ball for a long time before throwing it. In this mode, Chris can take extra bases to a envelope-pushing degree, routinely scoring on balls hit to the outfield as his batter runs to the next base as the opponents throw late to the one before. He has learned to time his swings and uses good strategy for mixing up his pitches: it's rare for him to even fall behind when playing this way.

In Medium mode, the fielders have a little bit more on the ball and the hitters make more solid contact. There is a significant chance that the computer can throw you out on the basepaths and actually scrape up some runs, including homers. A Medium opponent can beat you a nontrivial percentage of the time.

Chris has progressed far enough that he routinely takes double-digit leads in Easy mode, but there is a careful balance to be struck. At a certain point, the computer realizes it's getting it's proverbial rear end kicked, and makes some adjustments to keep the game "interesting." At least, I assume that's the theory: a team down 22-0 doesn't suddenly start hitting consecutive home runs without some software intervention involved. But this is where Chris' inability to tolerate frustration really comes to the fore: logically, the opponent can slug twelve consecutive home runs and you're still killing it, but even a glimmer of negative performance can send Chris into a tailspin.

Once it was clear that Chris had mastered the Easy mode, my wife encouraged him to play Medium. This is a natural progression: you develop mastery, then challenge yourself to perform at a higher level so that you can develop mastery there as well. This is the philosophy of his teacher giving him third-grade math assignments while he is in second grade, and is one of the driving principles of The Rest of Your Life. This natural progression is lost on Chris, though: he would much rather continue to show mastery where he has it than do something that demonstrates he lacks mastery. The "boredom switch" seems to be set to "off" in Chris: the rush of positive feeling from performing a skill doesn't seem to diminish nearly as quickly for him as it does for his peers or his brother. Either that, or the flood of negative feeling from not performing a skill "adequately" is enough of a deterrent to stay back in his comfort zone.

It's possible that he will play and win competitive games at Medium level, but it will not happen this week. Instead, Chris has two different coping mechanisms: he will "tank" games in Easy mode, where he will get a comfortable lead then intentionally make outs so the computer does not kick into "embarrassment recovery mode," or he will watch the computer play against itself.

The best baseball hitters still make outs well over half the time they get to bat: the best baseball team in history (in terms of raw winning percentage) still lost more than 1 of every 4 games they played. A team can lose 2 of every 5 (on average) and still be considered very good. Even the best team will lose three in a row at some point; the best hitter will take a collar, the best pitcher will give up runs. Conversely, the most sad-sack performers will have success, and likely at some point against you. In football or basketball, disparate talent normally yields the expected result, but baseball regresses to the mean faster than any other sport. I am wondering if the software company makes "Backyard Kansas State Non-Conference Football."

The year the Indians made their first trip to the World Series in my lifetime, Art Modell moved the Browns to Baltimore. This was considered plainly inconceivable, but it happened nonetheless. Browns fans reacted with remarkable emotion, persistence, and effect, garnering an expansion team in record time, but the Browns had moved. Apparently stung by the outraged reaction and the near-universal opposition from the national media, the NFL set the Browns up to fail by giving them far less time to put an organization in place than any other team before or since. And fail they did: their first regular-season game was nationally televised against the hated Pittsburgh Steelers, who beat the Browns four thousand sixty seven to negative eighty. (It was actually 43-0, but ask any Browns fan if it was that close. Then duck.) The "game" was a train wreck from start to finish: I promised I would watch until the Browns got a first down, and was forced to stay into the second half.

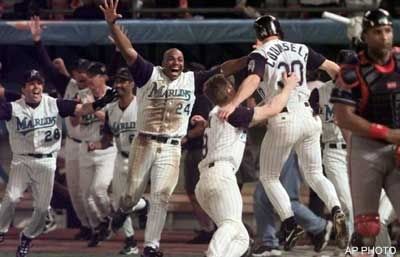

The Indians had become a legitimate power, though, winning the Central four more consecutive times and making another World Series in 1997. The Indians had the lead ... in Game Seven ... with their closer on the mound ... and lost to the expansion Wild Card Florida Marlins. The Marlins then dismantled their team, stunk to high heaven, and have since won ANOTHER World Series. Arizona has won a World Series. The Boston Red Sox have won the World Series. Cleveland has not been back.

Red Sox fans were whiny. Yes, their team had not won a World Series since 1918, but in my forty-year lifetime they had the best basketball team on the planet TWICE and now sport the model NFL franchise. I can appreciate that the Red Sox had lost in excruciating fashion, but it's not like Boston sports fans never had anything else to fall back on.

Chicago Cubs fans are whiny. Yes, their team has not won a World Series for almost 100 years, but unless you are over 100 years old, what is the difference between not winning since 1908 and not winning since 1948? I am forty years old. Am I supposed to take some satisfaction that Early Wynn pitched after Tinker, Evers, and Chance turned double plays? The wonderful columnist Bill Simmons made the point that not only had he never seen a Red Sox World Series win, but neither had his father. I appreciate that. My father did not enjoy the last Indians title so much, though, since he was nine, was living in Maryland, and did not follow the Indians. Perhaps I am selfish at consdering only my lifetime, but I think it's not too selfish. Besides, Chicago had the greatest NBA dynasty of my adult life and even had Da Bears. The Blackhawks stink, but that's just being greedy in my opinion.

Astros fans had the Rockets. Brewers fans had two different sets of Packers (and please don't tell me people in Milwaukee don't "count" the Packers). The San Francisco Giants fans had several sets of 49ers. The only fans I can feel real identification with are Buffalo fans, whose Bills lost Super Bowls with the same aplomb with which the Browns lost AFC Championship games, and whose Sabres lost to the Dallas Stars in the Stanley Cup Finals. (I took vicarious pleasure from the Stars win because the Cleveland franchise merged with the Minnesota North Stars which moved to Dallas. Again, we can be pretty desperate.) Buffalo does not have a major-league baseball team, but they've had AAA baseball for a while. In the eighties they started an affiliation with a major-league club and renewed it in the nineties. Players from the major league team filter through the Buffalo franchise on a regular basis.

The major-league team is the Cleveland Indians.

Chris gets excited when he sees me sneaking a glimpse at a baseball game while he is getting ready for bed. Admittedly, part of this is because he sees an opportunity to stay up a little more, but he likes to watch baseball with me, which is great. We watch one or two-inning snippets and he identifies things like the count, which team is home and which is visitor, the position to which the ball is hit, and scoring opportunities. It's special to see real enthusiasm for the simple act of watching a baseball game.

At our game at the Dell Diamond, the Oklahoma Redhawks broke a five-inning scoreless tie by scoring two runs while Chris and I were buying sodas and changing my daughter, but the Express came back to tie on a bases-loaded single. There was anxiety until the hit, since the Express were perceived as the "right" team to be rooting for. Also, the lack of scoring had weighed on Chris to that point: I hadn't thought of that. He was used to some scoring in virtually every inning of Backyard Baseball: scoreless innings in major-league baseball are hardly infrequent. Then in the eighth inning, an Express player lofted an opposite field fly into a tailwind, and it snuck over the right field wall. The Express won, 3-2, and we were able to enjoy the fireworks.

Since Chris had been enjoying the Backyard Baseball game at school (and when he is interested in something, he will talk about it a lot, a common manifestation of Asperger's), his teachers suggested he play some baseball during outside time. We had a bat and ball, but I went and bought a glove as well. We have been practicing catching a baseball with a glove, which is not a trivial task: he has been hitting underhand pitching for a while, but the glove is a new experience. There is a glow when he can catch several in a row, and we took the glove to the Express game. We'll watch more games and play more catch, although Little League is not in our collective futures. It simply wouldn't be prudent to even consider it.

The Yankees were struggling early this season, and Chris has released his attachment to them (he still likes Derek Jeter). I consider the mental image of George Steinbrenner screaming in his office and biting the doorknobs. This summer, we looked at the standings, and he declares that he is rooting for the Baltimore Orioles, Chicago White Sox, and St. Louis Cardinals. I cringe at the mention of the White Sox, a Cleveland division rival, but he knows the teams, he knows the sport, and he follows the results. It seems grossly unfair and selfish to ask for more at this point.

My wife is a native Texan, born in San Antonio and now living in Austin. She grew up rooting for the Dallas Cowboys, a team my family hated as Redskins fans, but there is history and memory there. In 2002, the Browns made an unlikely run into a playoff birth and faced the blasted Steelers in the opening round. The Browns took a big early lead, and I turned to my wife.

"You see," I said. "This is the difference between a Cleveland fan and a Dallas fan. If this were Dallas, you would be enjoying the performance, wondering how many points you would end up winning by. Since this is Cleveland, I am wondering how we're going to blow it." She laughed. I wasn't kidding.

Several touchdowns and a swing of bad two-point conversions later, the question of "how" had been answered. Objectively, Pittsburgh was the better team. Emotionally, it was simply more Cleveland Experience.

The Cavaliers have drafted the new Best Player On The Planet, and have managed to bollix the season to such a degree that there is serious question as to whether he'll stay. The Browns are on their third head coach and fourth starting quarterback since 2000, and aspire to catch the mighty Cincinnati Bengals (the Cincinnati Bengals! I have moved from sticks and eyes to heated pokers and spleens). The Indians have built an impressive stable of young talent which, thanks to a slow start, fell several hundred games behind the White Sox in the Central Division. And I still love them all.

After the All-Star Break, though, the Indians got very hot, and the White Sox grew mediocre and played sub-.500 ball. With a week to play, the Indians only needed to win 4 of their last 7 games to make the playoffs. With their (relatively) miniscule team payroll, they were ahead of the Yankees, caught the Red Sox, and were only two games behind Chicago. My friends on a discussion board were convinced that this was going to be the team that ended TCE. This, apparently, disturbed the cosmos. After playing at about an .800 clip, Cleveland dropped six of their last seven. They did not make the playoffs. When Chris is watching, I think we'll root for the Cardinals for now.

Nietzsche may have been right, but I'm not willing to find out. TCE might just kill him.

Jul 20, 2009 7:00 PM