Cavs Archive

Cavs Archive  The Enablers

The Enablers

As predictable as a mid-summer Indians’ trade for prospects are the inevitable inside stories about what really happened with LeBron James and his so-called decision to leave Cleveland. The latest was Andrew Wojnarowski’s inside look for Yahoo Sports.

As predictable as a mid-summer Indians’ trade for prospects are the inevitable inside stories about what really happened with LeBron James and his so-called decision to leave Cleveland. The latest was Andrew Wojnarowski’s inside look for Yahoo Sports.

Wojnarowski’s column is a good one, I guess, depending on the standards by which you judge such things. He talks about how James is mostly an uncoachable pain in the ass who almost was left off the 2008 Olympic team because of it. Wojnarowski also claims that no one could stand James on the 2004 Olympic team, either, and without the intervention of Nike, well, things might have been much different.

It was all Wojnarowski’s way of getting to his point that James’ decision to leave Cleveland was a long-time in the making and that maybe we’re all better off anyway.

That’s all well and good and may actually be true. My question, though, is why are we just hearing about this now? The answer to that question is simple. Its ramifications though go as long a way to explaining why James is the way he is, why athletes are the way they are and why fans are so ill-served by the traditional media folks that cover the games they love.

Stories like Wojnarowksi’s usually don’t come out until it's safe, such as when the athlete is discredited for other reasons. If Tiger Woods doesn’t crash his SUV on Thanksgiving night and literally unravel in full public view before his handlers could get out ahead of the story, his bizarre and self-destructive streak would still be hidden by his caddie, his agents, managers and assorted advisors and the media that covered him on a regular basis. So much of their livelihood depended on Woods that it was convenient to look the other way, to rationalize all his bad acts as supposedly being unrelated to his golfing greatness.

That’s the way it is with James. As much as I respect Brian Windhorst of the Plain Dealer, for example, I don’t recall even one story about James’ alleged difficulties playing nice with coaches of all stripes. There were slight hints, at best. I don’t recall Windhorst reporting, as Worjanowski does now, about how James’ boyhood buddies were literally running amuck inside the Cavs organization. Again, just hints at best. Windhorst is simply too good of a reporter not to have had the same information, and probably better at that, for months if not years.

But let’s not single out Windhorst. The same goes for each and every reporter covering the Cavs, including Wojnarowski. They were lock step in helping James and Nike craft the story arc of the local prodigy, messiah-like, delivering the long-deserved title for a dying city.

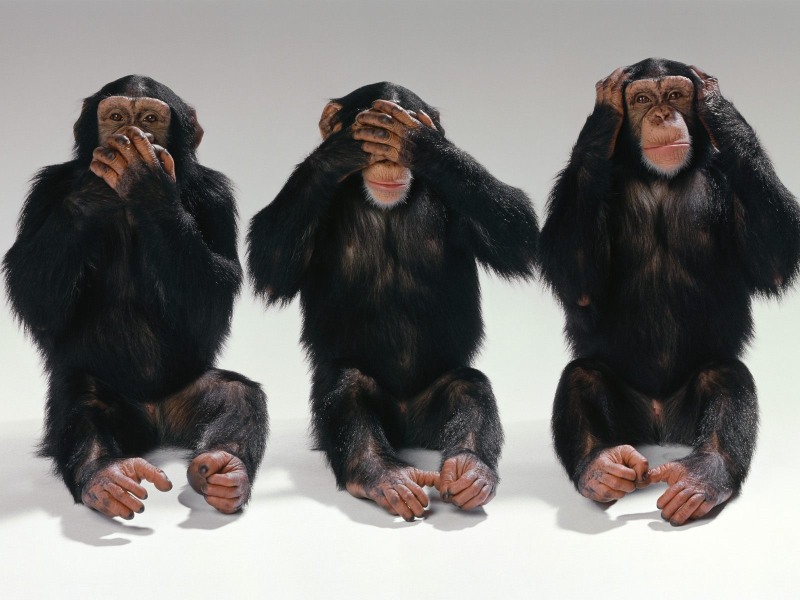

In his column Wojnarowski says that everyone referred to James’ gang as “The Enablers.” How deliciously ironic. Maybe Maverick Carter and the boyhood pals playing dress up in the most amateur of fashion possible were a gang of enablers, but they weren't the only ones. That group includes Wojnarowski and the rest of the traditional media such as ESPN that literally turned their network and journalistic integrity to James. Simply put, none of them did their jobs and now they look just as foolish as James.

Working journalists will tell you that so much of their ability to do their job depends on access to their subjects. That’s true, but not as completely true as the public is led to believe. A journalist’s role is to act as the eyes, ear and voice of their readers. In that role, journalists serve as important checks and balances to those in power, whether they are in the government or on the playing fields. Their function is to expose the truth and let the readers make up their own minds about what it all means.

In the world of sports, those maxims of journalism are just a rumor. Beat reporters since the days of Grantland Rice have been pulling punches about the athletes they cover because of the cozy relationships they maintain with them in order to preserve their access on the off chance that an athlete will actually say something of real interest. Editors have always looked the other way too because they view sports journalism as mostly sandbox play anyway.

When I took Indians beat reporter Paul Hoynes to task a few years ago for not having the journalistic integrity to take on general manager Mark Shapiro for supposedly hiding the injuries to Victor Martinez, Hoynes gave the predictable response: how come I never see you in the locker room? The implication of his rhetorical question was there are long-term interests a working reporter has to serve in order to do his job, something that is more difficult by the way if you go about alienating your with tough reporting about their shortcomings. In other words, supposedly if I had to face these players and club officials daily I, too, would pull my punches a bit.

While this mentality is rampant with sports journalists, it’s a part of journalism generally. One of the back stories in the whole Valerie Plame/Scooter Libby scandal had to do with the fact that a New York Times reporter, Judith Wilson, was revealed as being too cozy with and easily manipulated by her sources, like Libby, in order to preserve her access to them. As a result, it colored her reporting on the Iraq war and ultimately hurt the credibility of the Times.

Of far more recent vintage is the story surrounding Rolling Stone reporter Michael Hasting’s story on General McChrystal and his staff. Hastings, doing his job as a journalist, was able to ferret out one of the root causes behind all of the dysfunction in this country’s efforts in Afghanistan—divergent opinions within the command and an abiding lack of respect between McChrystal and his staff and the President and his staff.

Whatever you may think about the propriety of this kind of reporting about a working general in a war zone, what is at least as fascinating is how many so-called journalists took on Hastings for reporting the story in the first place. Their claim was the same as Hoynes’ complaint to me: that this kind of reporting only cuts off access and makes everyone else’s job all that much more difficult.

The problem with this mentality is that it makes the journalists complicit in creating the story the subject wants told and not the story that needs to be told. In other words, they become public relations tools of the subjects they cover rather than working journalists trying to find the truth. When the issues are so central to this country’s well being, it’s a very dangerous relationship. It matters little your political leanings to understand that if reporters are looking the other way when government officials are behaving badly, the country suffers.

Sports may be different because they don’t come with such serious ramifications, but let’s not kid ourselves that this is all harmless. LeBron James, like Tiger Woods, is an economic engine that helps line the pockets of dozens of people, from the bar owner outside Quicken Loans arena, to the publishers of the local paper who depend on readership of their stories about him to drive advertising revenue.

But in trying to preserve their access to this cash cow, all the reporters, including Wojnarowski, instead helped make James into the monster they now condemn. It may have been the primary responsibility of James’ mother, James’ agents, James’ sponsors, James’ buddies, to tell him to grow up and act like a man, but it was also the responsibility of the journalists covering him to call him out on that very topic each and every time they witnessed him being a jerk. And every time they didn’t, it emboldened James to newer and greater heights of jerkdom.

The Akronites and Clevelanders I talk with these days are all saying the same thing about James: it was his right to go wherever he wanted but they don’t like the way he handled it. Accepting the premise, it’s not hard to understand why James didn’t handle it the right way. No one, including alleged journalists like Jim Gray, was there to tell him otherwise.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)