Cavs Archive

Cavs Archive  Jeremy Lin: Hype, Hard Work, & The "Nice" Kind of Racism

Jeremy Lin: Hype, Hard Work, & The "Nice" Kind of Racism

Moments after the depleted Knicks upended the aging Lakers at Madison Square Garden last week, an ESPN message board asked, “Is Jeremy Lin the new favorite for NBA Rookie of the Year?” It seemed like a pretty reasonable question, considering the young point guard—making just his third NBA start—had dropped 38 points and seven assists on Kobe and the Lake Show, sending Spike Lee into hysterics and launching the term Linsanity into Twitter parlance. The only problem, of course, was that Jeremy Lin is not actually a rookie.

Moments after the depleted Knicks upended the aging Lakers at Madison Square Garden last week, an ESPN message board asked, “Is Jeremy Lin the new favorite for NBA Rookie of the Year?” It seemed like a pretty reasonable question, considering the young point guard—making just his third NBA start—had dropped 38 points and seven assists on Kobe and the Lake Show, sending Spike Lee into hysterics and launching the term Linsanity into Twitter parlance. The only problem, of course, was that Jeremy Lin is not actually a rookie.

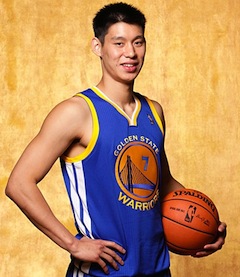

Somehow, like a mighty eagle trapped in a tiny canary cage, the Harvard-educated phenom spent the entirety of the 2010-2011 season at the end of the hapless Golden State Warriors’ bench, appearing in less than 30 games and averaging a shade under three points. To some, this revelation might cast the entire, overnight Lin sensation into doubt. After all, it was only a month ago that the undrafted guard was still an anonymous nomad-- outright released by two other teams and seemingly doomed for the D-League. And yet somehow, nothing about this story feels fleeting. Maybe it’s the appeal of an underdog conquering the Big Apple, or the polarizing Tebow-ness of Lin’s God-centric post-game interviews. But above all else, it’s the enormous weight he carries as an Asian-American sports star that will likely—for better or worse—prolong and define the Jeremy Lin drama.

The “Nice” Kind of Racism

ESPN may have been a little late to the party, but Jeremy Lin’s actual rookie season was carefully observed by at least some portions of the population. Nearly a year ago, I was first educated on Lin’s exploits by an Asian-American friend, who admittedly isn’t even that much of a basketball fan. The topic had emerged out of a general conversation on the state of the Asian-American in pop culture on the whole, with insights provided by two co-workers of mine— Mark (a Chinese-American from New Jersey) and Marisa (a Thai-American from Illinois). While the last U.S. Census tallied over 17 million people of Asian descent living in America (roughly 6% of the population), the representation of this minority group in anything other than a traditionally foreign and stereotypical light (ie, Jackie Chan kicking people in the head) boiled down to a sad handful of examples: “Well, there’s Harold from Harold and Kumar,” Mark said. “He’s okay. Um, Lucy Liu, I guess? She hasn’t been in anything in a while.”

“Oh, that annoying woman from Grey’s Anatomy,” chimed Marisa. “Whatever her name is [audible sigh].”

When the focus shifted to the world of sports, the exploits of stars like Ichiro, Yao Ming, or even Shin-Soo Choo were dampened a bit by the fact that these men were natives of Japan, China, and South Korea, respectively, and thus greeted and treated more like foreign dignitaries than fellow Americans. Making matters worse, in many cases, the most well-meaning fans often have a way of showing their admiration through the most ignorant of means.

Several years ago, for example, Chicago Cubs fans excitedly rallied around free agent signee Kosuke Fukudome by creating a wide variety of original merchandise inspired by the former Japanese League star. Unfortunately, these generally included stereotypical anime-style renderings of the Cub logo with hilarious phrases like “Horry Kow!” (you know, like how Harry Cary would say it if he were Japanese!). Similar sorts of playfully racist shirts and signage would have caused far more significant uproars if targeted at Latino or African-American members of the Cubs. But thanks to numerous complex historical and socio-economic factors, the PC police rarely come to the aid of the Asian community with quite the swiftness or gusto as some other prominent American minority groups. Add in the language barrier between American sports fans and the majority of Asian athletes, and the ability to break down age-old stereotypes proves all the more challenging. Yao and Ichiro may have been cheered enthusiastically and elected to numerous all-star teams, but part of their popularity would always be rooted in a sometimes-unhealthy American fascination with “the unknowable other.”

Several years ago, for example, Chicago Cubs fans excitedly rallied around free agent signee Kosuke Fukudome by creating a wide variety of original merchandise inspired by the former Japanese League star. Unfortunately, these generally included stereotypical anime-style renderings of the Cub logo with hilarious phrases like “Horry Kow!” (you know, like how Harry Cary would say it if he were Japanese!). Similar sorts of playfully racist shirts and signage would have caused far more significant uproars if targeted at Latino or African-American members of the Cubs. But thanks to numerous complex historical and socio-economic factors, the PC police rarely come to the aid of the Asian community with quite the swiftness or gusto as some other prominent American minority groups. Add in the language barrier between American sports fans and the majority of Asian athletes, and the ability to break down age-old stereotypes proves all the more challenging. Yao and Ichiro may have been cheered enthusiastically and elected to numerous all-star teams, but part of their popularity would always be rooted in a sometimes-unhealthy American fascination with “the unknowable other.”

A New Trailblazer (but not Portland)

And so, it’s easy to understand why a frustrated Asian American, feeling misunderstood and consistently under-represented, would have a perpetual eye out for somebody—anybody—to bridge that great divide. And what better sport than basketball for such a man to emerge? If any game seemed beyond the reach of the stereotypically small, nerdy, and unathletic Asian-American male, it was hoops. And thus, when Jeremy Lin signed a pro contract with the Warriors in 2010, it didn’t go unnoticed by everyone. Here was a Taiwanese-American, from Palo Alto, California, who spoke with no accent, had no Yao-like height advantage, and played with a swagger suited as much to the playground as the arena. Bench player or not, here was a guy who just might be able to make a real difference in how the general public views not just Asian-American athletes, but Asian-Americans as a whole.

Lin had the commitment, charisma, and most importantly—the actual on-court skills—to affect change, but he would need to seize his opportunity when it came. And as it turned out, it almost didn’t. After both Golden State and Houston cut him in December, Lin managed to catch on with the somewhat desperate Knicks, where he still saw limited action during a tumultuous first month of the season. In the end, it took an injury to Carmelo Anthony and the temporary absence of Amare Stoudamire to push Lin into the spotlight— finally given the keys to drive his own NBA offense for the first time.

What’s happened from there (namely, five Knick wins and five straight games of at least 20 pts and 7 asts) has been praised by opposing players, coaches, and TV commentators as a “magical run”—a showcase of Jeremy Lin’s “superior intelligence” and “surprising confidence.” But this particular selection of words only helps to indicate just how much more work Lin has in front of him.

Just Lin, Baby

Seen first and foremost as an oddity—a man visibly in contrast with both the skin color and body type of the typical NBA star in 2012—Lin’s initial challenge was the same one he’d already faced in high school and college: convincing people he belongs. Probably safe to say that mission is accomplished. Now, the question becomes how Lin will handle the new experience of high expectations— not just in terms of adapting to new defenses or sharing the ball with Anthony and Stoudamire—but as a somewhat unwitting ambassador for millions of Asian Americans.

While the media will assuredly continue to overlook his athletic skills in favor of his “Harvard smarts,” Lin will get an even more backwards brand of respect from portions of his growing fan base. As with Fukudome in Chicago, many of the signs have already started popping up in Madison Square Garden, typically designed by Caucasian kids with nothing but the purest of intentions. The other night, there was one that said “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Point Guard!” Another read, “Emperor Lin,” with a Japanese rising sun in the background (a fine example of white America’s general disinterest in the enormous differences between various Eastern cultures). Then there was sportswriter Jason Whitlock dropping a real classy tweet that—under different racial circumstances—would have had writers like Jason Whitlock calling for the tweeter’s job.

While the media will assuredly continue to overlook his athletic skills in favor of his “Harvard smarts,” Lin will get an even more backwards brand of respect from portions of his growing fan base. As with Fukudome in Chicago, many of the signs have already started popping up in Madison Square Garden, typically designed by Caucasian kids with nothing but the purest of intentions. The other night, there was one that said “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Point Guard!” Another read, “Emperor Lin,” with a Japanese rising sun in the background (a fine example of white America’s general disinterest in the enormous differences between various Eastern cultures). Then there was sportswriter Jason Whitlock dropping a real classy tweet that—under different racial circumstances—would have had writers like Jason Whitlock calling for the tweeter’s job.

This isn’t a Jackie Robinson sort of road Lin is walking down. He’s not likely to hear any fans tossing death threats at him. And he won’t be asked to turn the other cheek if another player takes issue with him. But in a way, he will still be blazing a trail, and such tasks are never accomplished without some adversity.

In all likelihood, Jeremy Lin would like nothing more than to be seen as simply a great basketball player, judged solely on his merits on the court itself. But after catapulting to fame within the space of two Saturday Night Live episodes, Lin has unavoidably transcended his sport, placed atop the highest of hash-tag pedestals by the caretakers of the Twitterverse. It may merely be his fifteen minutes—his Shane Spencer moment in New York’s notoriously short attention span. But for an Asian-American community desperate for their rightful representation, fifteen minutes can go a long way.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)