Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: Here’s What You Need to Know about Bill Wambsganss, See?

Cleveland Sports Vault: Here’s What You Need to Know about Bill Wambsganss, See?

I love old movies. It’s just that when I begin to watch them, I get distracted and lose interest. OK, maybe I mostly just like the idea of old movies.

I love old movies. It’s just that when I begin to watch them, I get distracted and lose interest. OK, maybe I mostly just like the idea of old movies.

I am fascinated by the social norms of earlier generations. In the early 20th Century, the United States certainly suffered from her warts; many of those involved racial overtones. But there was a structure to society that tended to hold most of her citizens to a code of honor and respect.

Early movies tend to reflect these mores. They also display prevailing patterns of speech of the times. I especially like the street smart character that commonly appears in these films. He uses language that can cause us to grin today (“private dick”). He’ll also employ a colloquialism on the end of a line, when he is giving someone “the what-for”: he’ll add “see?”

“You’re going to listen to me, see? And do exactly as I say.”

Today, it’s quaint. And fun to emulate. And besides its use as a forceful jab, it was also used in the same manner we use “you know” today. See?

Recently, I reviewed a chapter of the book The Glory of Their Times, The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It, by Lawrence S Ritter. We looked at the life and times of Hall of Fame pitcher Rube Marquard.

Today, I’d like to revisit that book. As its title indicates, the accounts within are transcripts of the ex-players’ own words.

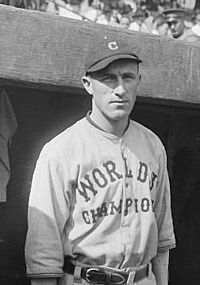

Among the various Clevelanders who are featured in the book is one who played most of his big league career in his home town. As displayed in Chapter 15, Bill Wambsganss liked to use the “-see?” colloquialism.

Baseball fans know the iconic story for which Wambsganss is famous. It occurred during the 1920 World Series, a best –of-nine affair that the Indians won in seven. The second baseman Wamby (as he was also known- newspapers shortened his name to fit it into their published box scores) recorded an unassisted triple play, the second in big league history and still the only one ever to be performed in a Series.

From the book, we learn that shortly after Wambsganss was born in Cleveland, his Lutheran pastor father was transferred to a church in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The boy’s future seemed preordained, one might say. He would become a minister, as well. The young Bill didn’t mind. It was just accepted as fact.

As he grew older and attended Concordia College in Fort Wayne, however, the young man began to question his life’s path. The big issue, the 800lb gorilla in the room that nobody talked about, was that Bill was deathly afraid to speak in front of people. In one case, he got up to address a group, and not one word came out of his mouth. He remained silent for an interminable amount of time before sitting back down.

This problem gnawed at him. He could not understand how nobody addressed it. He was on the path to seminary school in St. Louis, and nobody spoke up and stated the obvious: young Bill Wambsganss was not cut out to be a clergyman. He certainly didn’t have the nerve to tell his father.

While in college, Wambsganss also began playing baseball. He was a shortstop, and playing ball was his passion. He played with a fellow student whom had played some professional baseball. The manager of the Cedar Rapids ball club had written to him, asking if he knew of a good shortstop. Bill Wambsganss was his recommendation.

Wambsganss talked to his father, and worked it out so he could play with Cedar Rapids during the summer of 1913. The next year, he worked it out that he would be a school teacher through Easter (basically a college internship), after which he would again report to Cedar Rapids. He had a great season, and he was sold to Cleveland.

would be a school teacher through Easter (basically a college internship), after which he would again report to Cedar Rapids. He had a great season, and he was sold to Cleveland.

How would he approach his father? He rehearsed his talking points: He did not wish to become a minister. He did not think he would be a very good one. He always had wanted to become a professional ball player. He knew he was good, and now it was validated- the Indians had bought him.

In a huge surprise to the young man, his father agreed to let Bill do whatever he thought best. He was fully behind any decision Bill made. It lifted a heavy burden off the young man’s shoulders.

Bill always suspected that what helped immensely was that his father had always been a Cleveland baseball fan. He especially loved Larry (“Nap”) Lajoie. Bill joked that he wasn’t so sure his father would have been so supportive if he’d been sold to the Detroit Tigers!

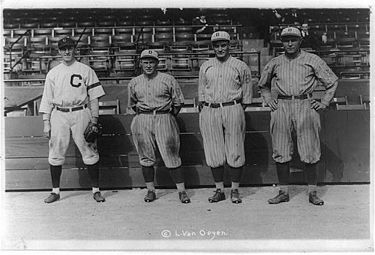

So Bill Wambsganss joined what was then known as the Cleveland Naps, in 1914. Their record wasn’t very good, but they had a talented roster. Shoeless Joe Jackson, Ray Chapman, Jack Graney, Steve O’Neill, and Terry Turner were all on the team. Chapman was entrenched as the regular shortstop.

So where was Wambsganss going to play? They started him out at third base. He remembered a story from when they played Detroit. The Tiger dugout, only 15-20 feet away from the third baseman, razzed Wambsganss unmercifully. He was surprised to note that as big of a star as Ty Cobb joined the chorus in getting on him, just a green rookie. Wambsganss shouted back at them.

Cleveland infielder Terry Turner had given the rookie some advice. When Cobb batted, to watch for whether he gritted his teeth. If he did, it was a decoy- a bunt was coming. When Cobb came up to bat, he indeed was gritting his teeth. Wambsganss cheated up closer to the plate- and Cobb swung away. A screaming line drive came right at him. He snagged the ball in one of those self-defense type of plays.

Eventually, the Indians (which they began to be called after Lajoie left in 1915) settled on Bill Wambsganss as their second baseman. He and Chapman formed a terrific infield combination. They were best friends, and Chapman told Wambsganss he would never play with another second baseman.

Of course, that was true. Chapman was killed after being struck by a thrown pitch at the Polo Grounds in New York during the 1920 season. It was tragic on many levels- his wife was pregnant, and he was going to quit baseball after that season. His wealthy father-in-law had a position waiting for him in his  business.

business.

After going into a tailspin through August, the Indians regained their stride and took the pennant. They would play the Brooklyn Dodgers (also known as the “Robins”, in honor of manager Wilbert Robinson) in the World Series.

In the pivotal Game 5 at League Park (named “Dunn Field” at the time, after the team owner), the Indians took a 3-2 Series lead. Everything went Cleveland’s way against spitballer Burleigh Grimes and the Dodgers. In the bottom of the first inning, Charlie Johnson singled. So did Wambsganss. Player-manager Tris Speaker bunted, and Grimes fell while trying to make the play. With the bases loaded, Elmer Smith hit a 1-2 pitch for a home run. It cleared the high screen above the short right field fence.

It was the first grand slam in World Series history.

By the top of the fifth inning, the Indians were up 7-0. The first two Dodgers singled. The infield was playing back; they needed to get one sure out, to keep a rally from developing. A double play was not the main goal.

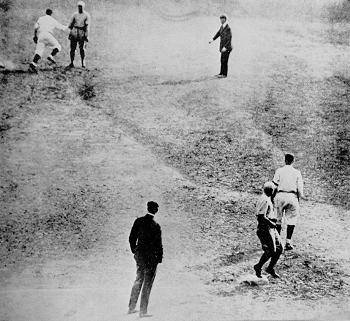

Clarence Mitchell, the Brooklyn pitcher who could hit, was up. He was a left handed pull hitter, so Wambsganss played him well back on the grass. With Jim Bagby pitching, Mitchell crushed a fastball to Wambsganss’ right. The second baseman moved to snag the ball (one out). His momentum was in the direction of second base, and he ran to it to double up the runner, who was almost to third base by now (two out). The runner from first base had also thought the ball  would not be caught, and he was nearing second. Wambsganss lightly touched him with the ball. And with that, he ran off the field.

would not be caught, and he was nearing second. Wambsganss lightly touched him with the ball. And with that, he ran off the field.

The home crowd in Cleveland was stunned at first. As Wambsganss approached the dugout, they broke out in a thunderous ovation. Straw hats were tossed onto the field, and the shortstop’s teammates surrounded him and patted him on the back.

The photo shows Wambsganss with the players he retired for the triple play. Photographers loved to pose the principals of a momentous occurrence. The three appear to be good sports about it- this looks like it could have been taken immediately after the game. The uniforms are still dirty.

Wambsganss, as it turned out, was somewhat ready for the play. A few seasons prior to his joining the Cleveland club, Naps player Neil Ball had made a similar play. Teammates had talked about it over the years.

Bill Wambsganss lasted a few more years in baseball. He played some with Boston and the Philadelphia Athletics before calling it a career. He spoke about how difficult it is for a ballplayer to retire.

Pretty compelling stuff. I’ll recommend the book, one more time.

“I’m not gonna tell you again, see?”

Here is a photo of the game-worn, triple play glove.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)