Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: Tribe’s “Lefty” Weisman, Spanning From Speaker to Veeck

Cleveland Sports Vault: Tribe’s “Lefty” Weisman, Spanning From Speaker to Veeck

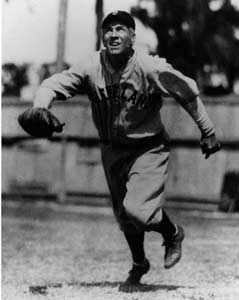

“Spoke” frequented the newsboy’s corner, a coveted (and fought-over) spot at Fenway Park - Broylston Street and Massachusetts Avenue - and was entertained by his soothing singing voice. The boy transitioned easily from Yiddish tunes to Irish ballads. Before long, Speaker (below right) had the boy entertaining the team in the Red Sox clubhouse. Max Weisman began hanging around during the team’s pregame warmups and soon earned his nickname. Eventually, he was running various errands for Speaker, as well.

Lefty Weisman’s family immigrated to Boston when the boy was an infant. In an oft-repeated story from the early 20th Century, young Max quit grade school. He was the oldest of seven children, and his newspaper sales helped support his family. Although in a way, the Red Sox became part of his extended family.

Speaker (also known as "The Grey Eagle") was acquired by owner “Sunny Jim” Dunn of the Cleveland Indians in 1916. He told the 20yr old Weisman he would  find a job for him with the team. It was the type of declaration that

find a job for him with the team. It was the type of declaration that most might dismiss as mere bombast. Spoke made good on the promise, sending for Lefty in 1919 when he became player-manager. He became an assistant to the team’s part-time trainer, Percy Smallwood, doing odd jobs around the locker room. And when Smallwood needed to retire in 1921 due to poor health, Lefty was the man.

most might dismiss as mere bombast. Spoke made good on the promise, sending for Lefty in 1919 when he became player-manager. He became an assistant to the team’s part-time trainer, Percy Smallwood, doing odd jobs around the locker room. And when Smallwood needed to retire in 1921 due to poor health, Lefty was the man.

Of course, he had no medical background or expertise, at first. He took the opportunity seriously, however, and studied to be a sports trainer at night, with experts at what is now University Hospital.

Lefty was like a son to Speaker. They spent hours- and dollars- together at Thistledown and bet on the horses on a regular basis. Sally (Mrs. Weisman) didn’t mind. Mostly. Most of Lefty’s days were full of jokes, gags, and quips. (A funny- and pointed- comment came from when young phenom- and future close friend of his son’s - Bob Feller joined the Indians. Feller told Weisman that his hat was too large. Lefty advised him to “keep it that way.”)

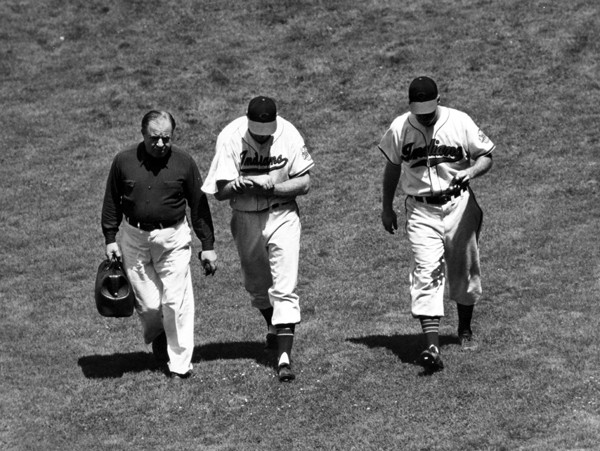

Photo on left was taken following Feller's first start. Holding his arm is Weisman. To the right is manager Steve O'Neill. Feller suffered some arm discomfort that day, and was held back from pitching for a while. Weisman reportedly declared Feller "popped an elbow muscle." Funny; quaint.

The Weismans’ two sons were like mini celebrities to their friends in the Cleveland Heights area. Often, Lefty brought home several ball players to dinner. “Sal” gamely accommodated the visits. It didn’t hurt that in polite company, most of the players were perfect gentlemen. Fred, the younger son (at the urging of team  owner Alva Bradley, the older was named ‘Jed’, as an acronym of the early Thirties Tribe outfield of Joe Vosmik, Earl Averill, and Dick Porter), speaks about hosting such guests as catcher Jim Hegan, pitchers Bob Feller and Bob Lemon, third baseman Ken Keltner – and entire groups of visiting teams. They’d feast, then head to the piano for a round of robust singing. (Notably not invited was Babe Ruth, whom Mrs. Weisman considered a “vulgar, rotten degenerate.” (!!!) )

owner Alva Bradley, the older was named ‘Jed’, as an acronym of the early Thirties Tribe outfield of Joe Vosmik, Earl Averill, and Dick Porter), speaks about hosting such guests as catcher Jim Hegan, pitchers Bob Feller and Bob Lemon, third baseman Ken Keltner – and entire groups of visiting teams. They’d feast, then head to the piano for a round of robust singing. (Notably not invited was Babe Ruth, whom Mrs. Weisman considered a “vulgar, rotten degenerate.” (!!!) )

1936 was a particularly memorable season for Fred; Lefty took him along on an extended road trip, for the experience. He became the team’s bat boy. Fred

First baseman Hal Trosky, whom was especially thrilled with the 'luck' he enjoyed in the boy’s presence, had a career year at the plate: a .343 average, 42 home runs, and a league-leading 162 RBI. Fred Weisman wore the Number 7 jersey of Trosky, from which Lefty had removed the sleeves (left).

By 1946, Bill Veeck (right) had purchased the Cleveland Indians franchise. Although he only owned the team for three and a half years, he immediately added to his legend as a showman. The blue-collar fan was king; Veeck went to such lengths as sitting in the bleachers to assess the game experience there (he noted the lack of ability to hear the P.A. system, which he soon rectified).

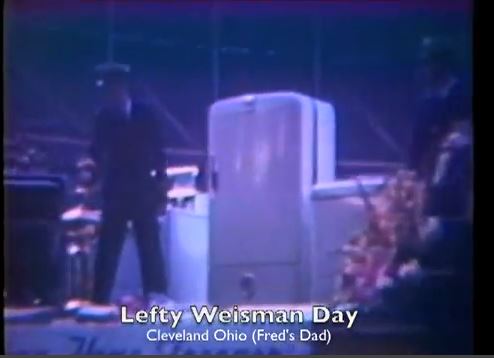

1946 also happened to mark the 25th anniversary of the trainer career of Lefty Weisman. In what appears to be the first day ever in big league baseball to honor a non-player (it wouldn’t be Veeck’s last, even in Cleveland), Veeck staged a Lefty Weisman Day. The team presented Weisman with all sorts of gifts, such as

Another notable portion of Lefty Weisman Day was the entertaining appearance of what Veeck began to consider his two “house acts”: Max Patkin and Jackie Price.

Patkin had been discovered by Veeck as a minor league pitcher. He appeared to be made of rubber, with the ability to bend, stretch, and contort his body as he ran or threw. He occasionally hammed it up for the crowd, who was ready for it. When Veeck heard Patkin hurt his arm, he signed him to his own minor league contract, with instructions to work on his clown act (and not to pitch).

Price was a shortstop whose specialty was what Veeck described as “feats of skill.” Price could catch and throw while standing on his head. He used a mini trapeze in the batter’s box, hanging by his knees and hitting pitched baseballs. He directed two catchers to squat side-by-side, and he’d simultaneously throw a fastball to one and a curve to the other. He’d drive a jeep through the outfield, shooting baseballs into the air from a pneumatic tube, and driving to where they would fall- he’d lean out far away from the driver’s seat and stab the ball backhanded as the jeep listed. There were other stunts as well…

This Is Your Life, a popular television series hosted by Ralph Edwards from 1952 to 1961, began as a radio show in the 1940s. In the show, Edwards would take a guest through his life, before a live audience. (surprise) Guest appearances were made by various family members, friends, and acquaintances. Through the radio years, the honorees ranged widely, from sportswriter Grantland Rice, to Audie Murphy (the most decorated soldier of WWII), to orchestra leader Guy Lombardo (the classic version of Auld Lang Syne popularly played every year for New Year’s Day is his).

In March of 1949, the show’s honoree was Tris Speaker. Ex-teammates Harry Hooper (from Boston) and Bill Wambsganss and Joe Sewell (from Cleveland) appeared. Indians player/manager Lou Boudreau had some nice things to say. Comedian (and lifelong Indians fan) Bob Hope provided comedy. Lefty Weisman also appeared on the show- and treated Speaker to an Irish Ballad backstage. (Unfortunately, no known recording of that particular show exists.)

Later in 1949, Lefty Weisman died at home and in Fred’s arms, from a heart attack. At his funeral, the gravelly-voiced Tris Speaker gave a sobbing eulogy. He bid farewell to his “son.” Lefty was fifty-four. An early demise, even in those days- but all who knew him were glad for the full life he’d led.

***Hey, follow me on Twitter! http://twitter.com/googleeph2 #thanks

Sources included The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia by Russell Schneider; Tales From the Tribe Dugout by Russell Schneider; The Cleveland Indians by Franklin A. Lewis; Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick by Paul Dickson; Every Tiger Has a Tale by Gary Stromberg; Veeck – As in Wreck. The Autobiography of Bill Veeck by Bill Veeck and Ed Linn; Tris Speaker: The Rough-and-Tumble Life of a Baseball Legend by Timothy M. Gray; Batboys and the World of Baseball by Neil David Isaacs; Tribe Memories, the First Century by Russell Schneider.

Also, check out this 2005 interview of Fred Weisman.

Photo below is of Weisman assisting pitcher Don Black, who collapsed from a brain hemorrhage in 1948 while batting during a game. Black would be hospitalized, lapsing into a coma. He recovered, although his playing career was over.

Weisman assisting outfielder Hank Edwards, whom had collided with the Stadium's chain-link outfield fence.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)