Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Druggies

Druggies

Blame it on the law of unintended consequences.

Blame it on the law of unintended consequences.

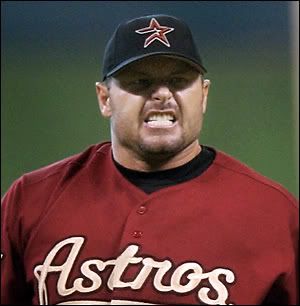

By naming names in the report he prepared for Major League Baseball on the use of performance enhancing drugs, former Senator George Mitchell unwittingly turned much attention away from the long-term, mostly ignored drug problems that still plague baseball to this day and toward figuring out exactly what was flowing through those needles that found themselves stuck to Roger Clemens' butt.

And now, of course, a veritable cottage industry has arisen almost over night in terms of figuring out who's telling the truth in the on-going soap opera between Clemens and his former best friend and personal trainer, Brian McNamee. Clemens doesn't deny being a drug abuser, only that the abused drugs were steroids. He admits to downing Vioxx, a now discredited prescription pain reliever, as if they were Skittles and was regularly shot with Lidocaine, a prescription anesthetic. His trainer, under the threat of going to jail if he didn't tell the truth, claims otherwise.

It's an interesting debate that will probably decide the ultimate fate of Clemens' legacy, but it is mostly a sideshow, which is a shame. The real issue is why baseball still won't come to grips with the full scope of its drug problem.

On Tuesday, the House Oversight and Reform Committee held another hearing on steroids in baseball, a follow up of sorts to Mitchell's report this past December. Commission Bud Selig, as expected, fell on his sword and adopted a mostly "the buck stops here" attitude, an approach that was convenient but meaningless given the simple fact that the drug culture flourished for years and years under his watch. Union president Donald Fehr, on the other hand, hedged a bit when trying to do the same but mostly came across as an ill-informed boob with little concern about the long-term health effects of the union members he claims to represent.

There was enough to titillate the average fan when a fair amount of the hearing was spent on Clemens, Miguel Tejada and the lengths to which San Francisco management went to protect its money tree, Barry Bond. But another focus of the hearings garnering a bit less attention was the flaws in baseball's existing drug policies, despite Selig's continued insistence that the programs are world class. Hardly.

Representative John Tierney of Massachusetts, for example, used the hearing as an opportunity to shed light on the issue of amphetamines. The back story is that amphetamine use was open and notorious in baseball (and probably most sports) for decades. In 2006 baseball finally outlawed their use and began testing for them. At the same time, however, it created a "therapeutic-use" exemption, meaning that any player who could con a doctor into writing a note could continue to use prescription amphetamines without penalty. The diagnosis of choice has been Attention Deficit Disorder and the drug of choice Ritalin.

In the first year of amphetamine testing, 28 players received the exemption, which basically mirrors the general population. But for reasons that neither Selig nor Fehr could explain, that figure ballooned to 107 the next year a figure that Tierney said was now eight times the general population. Selig did submit that they were trying to figure it out. The question, as always, is how hard.

In a story in Wednesday's New York Times, Tierney expressed his frustration that Congress shouldn't have to keep holding hearings in order to get baseball to address these problems. But if Tierney was frustrated coming out of the hearing, one wonders how he must have felt after reading the Times story in which Rob Manfred, baseball's vice president in charge of labor relations, essentially downplayed the whole issue by saying that the Commissioner's office, meaning Selig, really wasn't all that concerned, even as Selig seemed to say otherwise. Added Manfred, "nobody knows why it jumped."

Really? Nobody can figure that out? Maybe Manfred and Selig need to think outside the box and consider the crazy notion that it has something to do with addicted players finding a loophole in a poorly-crafted policy and driving a truck through it. Getting a doctor to write a note isn't exactly the hardest thing to do. Ask the guy on the loading dock who bruised his finger at work and got the doctor to excuse him from work for two weeks. Better yet, ask Paul Byrd.

If that doesn't illuminate it for Manfred and Selig, they should try talking with Dr. Gary I. Wadler, an anti-doping expert and internist, who points out in the Times story that Ritalin and the like help a person concentrate while also masking pain and increasing energy and reaction time. In other words, it jumped because players continue to crave a chemical edge and now have found a sanctioned way to make that happen. Duh.

But as reprehensible as baseball's casual indifference is toward the four-fold increase in one year in players who suddenly have ADD, more galling is their continued insistence that their drug testing policies have been effective. The therapeutic exemption is just one flaw. The fact that baseball only conducts a total of 60 unannounced off-season drug tests among its more than 1300 players is another. As Rep. Diane Watson of California said at the hearing, based on pure statistical probabilities, it's unlikely that the average player would ever be subjected to such a test.

Selig said the right thing, as he usually tries to do, that baseball is committed to a program that requires "adequate" unannounced testing, but he knows full well that any such agreement must be bargained with the union. Selig has never been able to adequately stand up to Fehr on virtually any issue and nothing Fehr said at the hearing suggests he will be any more agreeable now. The truth is that Selig and his fellow owners lack the will to place the integrity of their sport and the health of their players above their own economic interests. If it comes down to shutting down the sport in order to gain a meaningful, meaty drug testing policy, everyone, including Selig and Fehr, knows damn well which interest will prevail.

Another major flaw in the program, as highlighted by John Fahey, the president of the World Anti-Doping Agency in a story in the USA Today, is baseball's continued insistence that it run its testing program in-house. "Professional baseball's response to Sen. Mitchell's report is baffling," Fahey said in a statement, according to the story in USA Today. "To suggest that it might continue to keep its anti-doping testing program in-house ... is demeaning to Sen. Mitchell and the congressional committees who view doping as a serious threat to public health." As Fahey points out, an in-house program ultimately lacks accountability and helps foster the problems that are just now coming to light, such as the unexplained increase in therapeutic-use exemptions.

But Fahey reserved his biggest criticism for what he called baseball's "blatant disregard for the truth" when it comes to testing for HGH, human growth hormone. Selig and Fehr continue to insist that there is no validated urine test for HGH, which is technically true. However, according to Fahey, there is a reliable blood test for HGH and, more importantly, the taking and storing of blood now for future testing is widely in use. The problem, of course, is that baseball's testing policies do not allow for the drawing of blood let alone for punishment tomorrow for a positive test yesterday.

Left to their own accord from here on out, baseball likely would do nothing more than it's done already and, if they could get away with it, would probably rescind half of what they have done. When it does move, it's not because it's for the good of the game but because a bayonet, in the form of the threatened repeal of their anti-trust exemption, is pointed at their eye sockets.

If you see a pattern in all of this, you're not alone. Selig and Fehr like to talk a good game but their actions speak much more loudly. They want to appear to be tough on drugs but lack the philosophical conviction, not to mention the political will, to do what it would really take to ensure the public that their sport is both honest and clean. At the moment and for the foreseeable future, it's neither.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

skatingtripods (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:52 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)