Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Memories of '95

Memories of '95

Sometimes it’s hard to believe it’s been fifteen years since the greatest Cleveland team I’ve ever seen.

The 1995 Cleveland Indians went 100-44. They led the American League in batting average, slugging percentage, on-base percentage, runs scored, home runs and stolen bases. They led in team ERA- were the only team in the AL with a team ERA under 4.00, in fact. They finished fourteen games better than any other team in the league, dominating the circuit as few clubs have before or since. They were… awesome.

But this story begins before 1995, when the Indians were, like now, the worst team in baseball. And they had been for longer than I’d been alive.

The Bad Old Days

I can remember sitting on the bench during a Little League game at Plum Creek Park in Kent in the summer of 1987 (I was a centerfielder with decent wheels, a decent glove, absolutely no bat and the arm of a six-year old girl; think Ray Oyler, only in the outfield) when the Indians were well on their way to one of the three 100-loss seasons they endured in a seven-year span, and overhearing two fathers complaining about the recent trade of Tony Bernazard to Oakland. The previous year the Tribe had won 84 games and finished fifth in the American League East, eleven-and-a-half games off the pace. The fathers didn’t appreciate that team being “broken up,” as if this was Charles O. Finley selling off the early ‘70s Athletics.

Fans in those days were famished for even decent baseball. If the Tribe won five or six games in a row, all of a sudden there would be 50,000 people at the Stadium for a weekend series. Then they would go into their inevitable “June swoon” and it would be back to the usual crowd of 6,000. Gabe Paul used to describe Cleveland as a “sleeping giant” when it came to baseball- that the city would come out in huge numbers to support a winner. As it turned out, Mr. Paul was right. But no one below the age of about 45 had ever known what contending baseball in Cleveland even resembled.

The Indians had last fielded an actual pennant contender in 1959 when they finished second, five games behind the Go-Go White Sox. (My father, who was 13 that summer, always complains about that season; the Tribe was better, he says; they just couldn’t beat Chicago. Sure enough he was right- Cleveland went 83-49 against the rest of the AL, five games better than Chicago’s 78-54, but went 6-16 against the White Sox. In 2005 I would feel my father’s pain.) From 1960 through 1993 Cleveland would finish no higher than third (and that only once.) Not once did they come within ten games of winning either the AL in general or the AL East in particular.

And the Tribe had graduated from perpetually mediocre to perpetually awful by the time I matriculated into fanhood. I was born in 1975 and started following the Indians in 1983. I’d been a fan for about eleven years going into 1994. In that time I’d seen three 100-loss seasons. You youngsters think 2010 is bad? Multiply it by three. I’d seen one winning season, 1986, and that club wasn’t even close to contending for a title of any kind. I knew one kind of baseball- the losing kind. I didn’t know any other kind existed around here, and neither did anyone else born after about 1955.

The Indians hit rock bottom in 1991, going 57-105- their worst season ever. But there were signs of a revival amid the rubble. Despite being sent to Triple-A Colorado Springs for a few weeks in June for not running out a double-play ball, 25-year old Albert Belle belted 28 home runs to lead the team. 22-year old Carlos Baerga hit .288 in his second season and knocked in 69 runs. 24-year old Charles Nagy pitched respectably despite losing 15 games. 25-year old Sandy Alomar had an injury-plagued season on the heels of his Rookie of the Year Award in 1990, but a bright future was still projected for the big catcher.

The Tribe also had in place the manager that would lead them to heights they hadn’t seen since the 1950’s. Former Indian first baseman Mike Hargrove took the job when John McNamara was fired midway through the ’91 season. Never a great tactician, Hargrove was a calm, strong presence with the perfect demeanor to handle the mix of volatile personalities that would soon fill the Cleveland clubhouse.

There was more help coming down on the farm, in the form of a pair of prodigious young batsmen. 21-year old Jim Thome continued an assault on minor-league pitching that had begun almost as soon as the husky kid from Peoria was selected in the 13th round of the 1989 amateur draft. And in the 1st round of the 1991 draft the Tribe selected a 19-year old high-school phenomenon out of New York City named Manny Ramirez. The present couldn’t have been more dismal. But for the first time in a long time, there was the notion of a future.

Light at the end of the Tunnel

That notion sharpened in 1992. Belle, Baerga and Nagy each had breakout seasons. Belle smashed 34 home runs and knocked in 112; Baerga became the only second baseman since Rogers Hornsby to bat .300, hit 20 home runs, knock in more than 100 runs, and get more than 200 hits; and Nagy blossomed into one of the game’s most promising pitchers, going 17-10 with a 2.96 ERA. 27-year old Steve Olin, a tough-minded sidearm specialist, solidified the back end of the bullpen with 27 saves. Meanwhile, Thome and Ramirez continued to hammer their way up through the minor-league ranks.

Immediate help was on hand as well, thanks to a series of shrewd personnel moves by general manager John Hart. Fastball-firing righty Eric Plunk arrived as a free agent to bolster the bullpen. In December of 1991 Hart traded catcher Ed Taubensee and pitcher Willie Blair to the Astros for infielder Dave Rohde and a former University of Arizona point guard-turned-outfielder named Kenny Lofton. In another under-the-radar deal Hart swapped a pair of minor-league pitchers to the Twins for first baseman Paul Sorrento, made expendable in Minnesota by the bulky presence of Kent Hrbek. Midway through the ’92 season Hart dealt outfielder Kyle Washington to Baltimore for wild young right-hander Jose Mesa.

Plunk and Sorrento were pleasant surprises in 1992, but the big revelation was Lofton, who won the centerfield job in spring training and proceeded to belie his reputation as an ineffective hitter. The speedster hit .285, fielded sensationally, led the American League in stolen bases with 66, and finished second in the Rookie-of-the-Year voting to Milwaukee’s Pat Listach. (Lofton is probably still miffed over that.) With Lofton setting the table and Baerga and Belle clearing it, the 1992 Indians improved tremendously from their dismal ‘91, going 76-86. For the first time in a long time, there was optimism surrounding Cleveland baseball.

That optimism would be tempered by tragedy, however. On March 22, 1993, during spring training, Steve Olin and fellow pitcher Tim Crews were killed when their bass-fishing boat collided with a dock on Florida’s Little Lake Nellie. The accident devastated the club, which wandered aimlessly to another 76-86 finish in 1993, the last season at old Municipal Stadium.

(I wonder sometimes if Cleveland’s fortunes would have been different had Olin lived and become the longtime closer instead of Jose Mesa. Olin’s stuff wasn’t as good as Mesa’s but he had a better mentality for the closer’s role; he didn’t get rattled, went after hitters and could put a bad outing in the rearview mirror much more quickly than Mesa. Olin wouldn’t have tried to tiptoe around those Florida hitters in Game Seven of the ’97 World Series; he would have trusted his stuff, for better or for worse. But Little Lake Nellie was a human tragedy, not a Cleveland sports tragedy.)

Despite the horror of Little Lake Nellie, the club’s core continued to improve. Albert Belle enjoyed one of the finest seasons ever by a Cleveland slugger, belting 38 home runs and knocking in 129 to lead the American League. Carlos Baerga put together his second consecutive .300-average, 20-home run, 100-RBI, 200-hit season. Kenny Lofton upped his average to .325 and again led the AL in steals with 70. The Indians would move into Jacobs Field, their new 43,000-seat playground, in 1994- a season anticipated like few before or since.

In the winter of 1994 John Hart added some veteran leadership to his young club. 38-year old designated hitter Eddie Murray and 39-year old pitcher Dennis Martinez had both been rookies in 1977, and both were products of the same Baltimore Orioles system that had produced Hart himself. Both would prove to have plenty of gas left in the tank. At the same time prize farmhands Jim Thome and Manny Ramirez became full-time regulars for the first time. And to top it off, Hart made perhaps his most important deal of all, when he flipped shortstop Felix “El Gato” Fermin and prospect-turned-suspect Reggie Jefferson to Seattle for 27-year old shortstop Omar Vizquel.

Some trades are so lopsided you know they’re steals as soon as they happen. The trade that brought Omar to Cleveland was one of those. I can remember hearing about the trade and thinking: We got Omar Vizquel for THOSE guys? Omar was already perhaps the premier defensive shortstop in the game and although his bat hadn’t caught up to his glove, he certainly seemed to hit Cleveland pitching well enough. Besides, we had as many bats as we could want already. Not knowing the Mariners had another shortstop in the pipeline- kid named Alex Rodriguez- I couldn’t believe we got such a great player for virtually nothing.

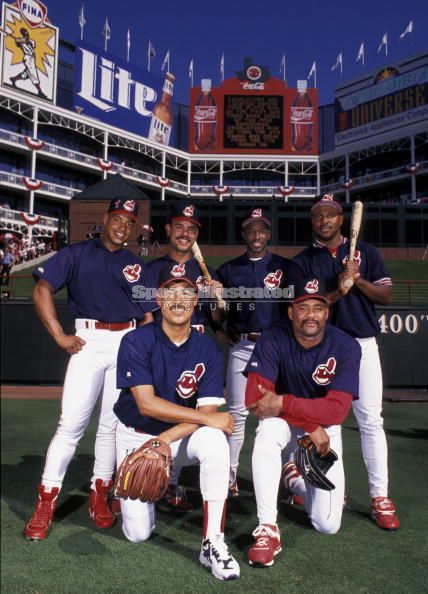

All of the pieces to the most talented lineup since the Big Red Machine- Lofton, Vizquel, Baerga, Belle, Murray, Thome, Ramirez, Alomar and Sorrento- were on hand. The beautiful new park was set to open. In retrospect, it all seemed preordained- and it seemed that way at the time, too. Something special was afoot; you could feel it, taste it.

Breakout Year

Breakout Year

In some ways, 1994 is still my all-time favorite Indians season. It was the first time in my life that the Tribe was really, truly, legitimately good. There’s nothing like seeing a young team blossom into a powerhouse, seeing the vision crystallize into reality. I’d experienced it before with the 1988-89 Cavaliers; but this was different. This was the Indians. I was a far bigger baseball fan than basketball fan growing up. A great Cavaliers team was nice to see. A great Tribe team was way beyond that. It was an impossible dream.

The Indians opened Jacobs Field on the chilly afternoon of April 4, 1994, against the Mariners. In what would become a typical performance in the park, the Tribe came back to win. Despite being no-hit for seven innings by Randy Johnson, Cleveland tied the game 2-2 with a pair of runs in the eighth. Down 3-2 in the eleventh the Tribe came back to tie it again and they won it the next inning on Wayne Kirby’s RBI single. Cleveland raced out to a 6-1 start before ennui set in. The Tribe slumped hard and by the second week of May was scuffling along at 14-17. Included in the meltdown was Omar’s quasi-legendary three-error game against the Kansas City Royals. In Cleveland the collective mood was: here we go again.

Then things fell into place. The Indians went on a 27-8 tear, including a ten-game winning streak, to vault into first place with a 41-25 record. One of those wins was a game I’ll never forget. It was on June 16, 1994. Trailing Boston 6-4 in the bottom of the ninth the Indians scored three runs, the final two on a Texas-League single by Albert Belle with two outs, to win 7-6. That warm night, with more than 41,000 jumping for joy at the Jake, the Indians seemed to arrive- and the phenomenon known as Jacobs Field Magic began in earnest. From that night on, it seemed that the Tribe was never, ever out of a game at home. No deficit seemed insurmountable.

The 1994 season, of course, ended with the players’ strike on August 12. There were no Playoffs, no World Series. The Indians finished the aborted schedule with a record of 66-47, one game behind the White Sox in the American League Central. Had there been a postseason the Tribe would have qualified as the wild-card team. Some would say they would have won it all that year; I’m inclined to think the Expos, the Yankees (who went 9-0 against the Indians that season) and the shaky Cleveland bullpen might have had something to say about that.

And looking back on it, it seemed most everyone knew that the strike, while disappointing, was just a small bump in the road. The Indians weren’t done yet. With their young core, the future was dazzlingly, impossibly bright. It wouldn’t take long for us to find out just how bright that future was- in 1995.

1995

While other clubs, hurt financially by the strike, were dropping ballast in the winter of 1995, the Tribe continued to make additions. The biggest was 36-year old pitcher Orel Hershiser. The Bulldog had struggled since winning the 1988 National League Cy Young Award and hurling the Dodgers to that season’s World Championship, going 51-53 in the next six seasons. But he had the leadership, savvy and postseason experience the Tribe craved, and would prove to be worth his weight in gold in the coming season.

Due to the late resolution of the strike, Major League Baseball had only a 144-game schedule for 1995, with Opening Day on April 27. The Tribe got started in style that day, clubbing three Texas pitchers for 13 hits, including five home runs, in an 11-6 thrashing. Cleveland lost the next two in Arlington to fall under .500 for the only time that season, then got back to the break-even point with the first of what would become 13 extra-inning victories without a loss that season.

The real tone-setter for 1995 came on May 7, when the Tribe overcame the Twins 10-9 in a 17-inning marathon at Jacobs Field. That win brought Cleveland’s record to 6-4 and from there, the wins began to pile up in bunches. After the two-game losing streak in the opening week, the Tribe would not drop consecutive games until late June- by which time they were 36-13 and had an eight-game lead in the American League Central.

It was truly an amazing season. When the Indians lost it was a surprise. If I missed a game, for whatever reason, and found out that the Tribe had lost, my reaction was raised eyebrows: “They lost? Really?” Even as it was happening it was hard to imagine. Four years earlier the Indians had lost 105 games. Now they didn’t just have a good team- they had a team of stars, larger-than-life superheroes. Manny Ramirez hit seventh in the lineup. That’s all you need to know.

With 31 home runs and 107 RBI Manny was the big breakout star in the lineup- but the surprise performances were in the Cleveland bullpen, which went from weak link to bona-fide strength in one season. 22-year old Julian Tavarez went 10-2 with a 2.44 ERA; Eric Plunk and Paul Assenmacher- another veteran acquired, like Hershiser, prior to the ’95 season- combined for a 12-4 record; but the biggest revelation was Jose Mesa. An ex-starter, Mesa was installed in the back of the bullpen and had one of the best seasons ever by a closer, saving 46 games- including 38 in a row- and compiling a 1.13 ERA. In those innocent days an appearance by “Joe Table” meant that victory was assured.

Yes, it was some kind of season. Funny thing, though. I went to four games in 1995. My personal record was 2-2. I was “fortunate” enough to witness the first time the Tribe was ever shut out at Jacobs Field, when they were whitewashed by Al Leiter of the Blue Jays (the man who would start Game 7 of the 1997 World Series for the Marlins.) I also went to four games in 1991, the year the Tribe went 57-105. My personal record that season was… 2-2.

The Indians would not formally clinch the division until September- but for all intents and purposes the race was over on Memorial Day weekend. That weekend Cleveland hosted the Chicago White Sox, who had led the Central at the time of the strike and who were expected to provide the stiffest opposition to the Indians in ’95. Chicago was struggling, however. At 11-16 the White Sox trailed the Indians by seven games going into the four-game set and badly needed a series victory to keep their flagging hopes alive- and preserve employment for embattled manager Gene Lamont.

Instead they got a dose of Jacobs Field Magic. Chicago methodically built a 6-0 lead going into the sixth inning of the series lid-lifter. The Indians sliced the deficit to 6-4 in that inning, getting three of the runs on a home run by another veteran offseason acquisition, Dave Winfield. It was the only big hit of the year for the 43-year old Winfield, who hit .191 in this, his final season- but it was very big indeed. Cleveland tied the game in the seventh and won it in the eighth on an RBI double by backup catcher Tony Pena. That was it for the White Sox- and for Gene Lamont. They went meekly in the remaining three games of the series, losing all three, and Lamont was fired at its conclusion.

From then on, the AL Central race was over. The final four months of the season was one long victory lap. But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t tension- far from it.

Nemesis in the West

In the midst of this glorious summer, Yours Truly was a regular Nervous Nellie. I knew the Tribe was going to the Playoffs- everyone did. I fretted all season about what would happen when they got there. I desperately wanted to see the Indians in a World Series, to see them play a National League team in the chilly air of October. To see the season go up in smoke before they got there would have been unbearable.

There was one potential opponent I sweated more than anyone else. It wasn’t the Red Sox, who led the AL East virtually the entire season. Nor was it the Yankees or the Mariners, both of whom struggled for much of the campaign. It was the California Angels.

California, on first glance, looked a lot like the Indians. They had a dynamic young core- 23-year old Garret Anderson, 25-year old Jim Edmonds, 25-year old Damion Easley, 26-year old Tim Salmon, 27-year old J.T. Snow- a veteran starting rotation (Mark Langston, Chuck Finley) and a solid bullpen anchored by Troy Percival and Lee Smith. The Angels were a scary team. They played the Indians five times in 1995 and beat them three times. The Tribe was fortunate to win the two. They needed extra innings to beat the Halos in Anaheim, and needed an Albert Belle ninth-inning grand slam off Lee Smith to beat them in Cleveland. California looked like a very tough match-up. And the Angels were hot for much of that summer, going 30-11 in July and the first half of August. I pondered a potential postseason meeting with California- and I took counsel of my fears.

Looking back on 1995, I regret not enjoying the season more. I was a worry wart- worried about the Angels, worried about the postseason, worried about the thought that the Indians might not make it to the World Series. I didn’t stop and smell the Folgers. But I wasn’t asking for much. I didn’t particularly care if the Indians actually won the World Series. I just wanted them to get there.

And as it turned out, I shouldn’t have worried about the Angels after all.

Memories

Some moments from that season burn a little more brightly than others. Certain sequences stick out:

- June 30: Eddie Murray strokes his 3,000th hit against the Minnesota Twins in the Metrodome. Tom Hamilton’s voice cracks like Peter Brady’s as he makes the call.

- July 16: With two outs in the bottom of the twelfth, Kenny Lofton on second and the Indians trailing Oakland 4-3, Manny Ramirez battles Dennis Eckersley for six tense pitches, then turns on the seventh and blasts it deep into the left-field bleachers to win the game for Cleveland. The television camera follows Eck’s face as he watches the ball sail into the stratosphere and mouths a single word: “Wow!”

- Waking up from lung surgery at Akron General, heavily sedated in the recovery room, and asking the nurse through the haze of painkillers, “Did the Indians win?” (They did.)

- The blaring sound of the club’s unofficial theme song, “This is How We Do It” by Montell Jordan.

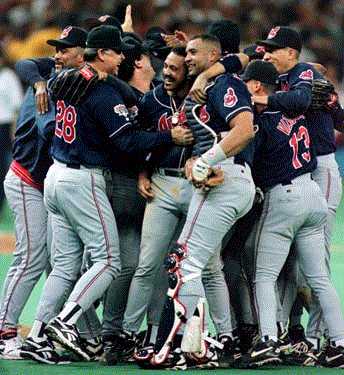

- Going to the 100th win in the final game of the season, a 17-7 rout of Kansas City. After the game Kenny Lofton gave a short speech to the sellout crowd, a speech he included with the admonishment: “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.” Naturally, the BTO song of the same name immediately kicked in and the 42,000 on hand- including Yours Truly hard by John Adams in the back row of the bleachers- clapped along in celebration of a season we couldn’t have anticipated in our wildest dreams.

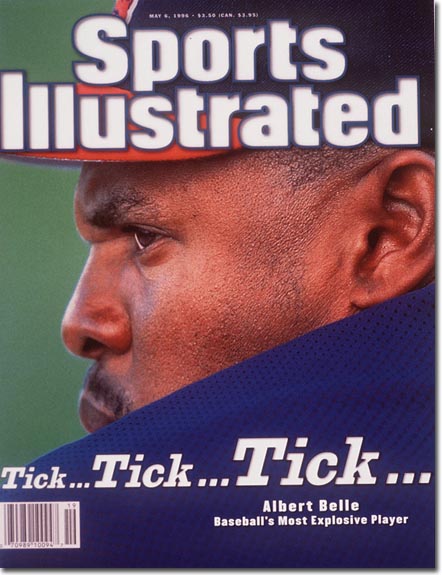

And then, there was Albert Belle.

Albert Freaking Belle

Actually, 1995 didn’t start particularly well for the mercurial slugger. After belting home runs in the first two games, Belle went nearly three weeks without a round-tripper. At the end of July- the 85-game mark- Belle still had only 19 home runs, well off his 1994 pace, when he had 26 bombs after 85 games. Indeed, for much of ’95 the Tribe’s leading home-run hitter was Manny Ramirez, who got off to a red-hot start that season.

But Belle was generally a slow starter, at least when he played in Cleveland. And when he finally got going in August, he became almost impossible to keep in the park. On three separate occasions in August Belle hit two home runs in a game, and he finished the month with 14 home runs, 30 RBI, a .381 batting average, a .847 slugging percentage and a staggering 1.303 OPS. On the last two days of the month Belle clouted extra-inning home runs to beat the Blue Jays.

And if Belle was great in August, he was off the charts in September. He started the last full month of the season with a home run and four RBI in a 14-4 bombardment of Detroit. Five multi-home run games followed, including five bombs in back-to-back routs of the White Sox on September 18-19. Belle’s numbers for September 1995: a .309 batting average, a .948 slugging percentage, 1.391 OPS, 17 home runs and 32 RBI. Of Belle’s 30 hits in the month of September, 27 were either doubles or home runs- which of course goes a long way toward explaining how the big slugger had fifty of both on the season.

Albert Belle played in a total of 57 games in August and September of 1995. He hit 31 home runs in those 57 games. Say what you will about his general likability- this was a bad, bad man. And back then, Cleveland fans loved him for that. The Tribe had been bullied for a long time. Now they had the ultimate bully. Crouching at the plate, glaring at the pitcher, Albert Belle was one of the game’s all-time intimidators- and our collective “**** you” to a baseball world that had been kicking sand in our faces for almost four decades.

And now it was time for the first Tribe postseason since 1954.

Sweeping the Sox

There was a time when the Boston Red Sox were just another ballclub- and the Cleveland Indians owned their souls. That time was 1995. Boston had the second-best record in the American League that season at 85-59 and they also had Mo Vaughn, who in an absolute travesty of justice won the league MVP award over Albert Belle. But in the end they would prove no match for the Tribe.

Still, Game One of the Division Series at Jacobs Field was dramatic, to say the least. It went thirteen innings and, with a pair of rain delays thrown in, lasted more than five hours. The Red Sox took a 2-0 lead in the third inning on a home run by John Valentin, the Tribe went ahead in the bottom of the sixth on a two-run double by Belle and a run-scoring single by Eddie Murray off Roger Clemens, the Sox tied it in the eighth on Luis Alicea’s solo shot off Julian Tavarez- and then it was on to a tense, tortuous extra-inning session.

Boston’s Tim Naehring broke the tie in the top of the eleventh with a solo home run off Jim Poole. But Albert Belle had the answer. Leading off the bottom of the eleventh, Belle lashed a bomb off Rick Aguilera and it was 4-4. At this point, mindful of the “Batgate” scandal from the previous season, when Belle was caught using a corked piece of lumber in Comiskey Park, Red Sox manager Kevin Kennedy tried his hand at a little bit of gamesmanship. He had the umpires confiscate the bat Belle used to hit the home run off Aguilera. If Kennedy was trying to get into Belle’s head he failed- miserably. The slugger appeared on the top step of the dugout and, facing the Red Sox dugout, flexed his meaty right bicep. The flex promptly became a symbol of Cleveland’s pennant charge, with fans bringing cardboard cutouts of Chief Wahoo in full-on Popeye pose.

The game went on, deep into the night. Cleveland put men on first and third with no outs in the bottom of the twelfth but Boston’s Zane Smith pitched out of the jam. With two outs in the bottom of the thirteenth and Smith still on the mound for the Red Sox, Tony Pena came to the plate. Pena had actually started at catcher for most of the season- Sandy Alomar being hurt, as was his wont- and was a fiery leader of the team. Several times during the season he came out to the mound and slapped Jose Mesa upside the head with his mitt when Mesa wasn’t showing the proper focus. But Pena’s biggest blow was forthcoming.

The game went on, deep into the night. Cleveland put men on first and third with no outs in the bottom of the twelfth but Boston’s Zane Smith pitched out of the jam. With two outs in the bottom of the thirteenth and Smith still on the mound for the Red Sox, Tony Pena came to the plate. Pena had actually started at catcher for most of the season- Sandy Alomar being hurt, as was his wont- and was a fiery leader of the team. Several times during the season he came out to the mound and slapped Jose Mesa upside the head with his mitt when Mesa wasn’t showing the proper focus. But Pena’s biggest blow was forthcoming.

Pena got ahead in the count 3-and-0. From the Tribe dugout emitted the sign for the next pitch: take. Pena either missed the sign or ignored it. He swung at Smith’s next offering and hit it high, hit it deep, hit it just over the 19-foot wall in left field. It was 2:08 on the morning of October 4, 1995, and the Indians had won their first postseason game since 1948. I remember feeling only relief after an emotionally exhausting five hours of baseball.

The Red Sox were done. They went quietly in the next two games, losing by a combined score of 12-2. The Indians didn’t even unpack their bags when they arrived in Boston for Game Three and as it turned out, they didn’t have to. Mo Vaughn didn’t get a single hit in the three-game series, going, as the phrase went, “Mo-for-14.” Boston’s second-leading slugger, Jose Canseco, went 0-for-12. The Tribe hit just .219 as a team; they won the series with pitching, holding the Red Sox to six runs and a team batting average of .184. Cleveland was now four wins away from the World Series.

Refuse This!

In the American League Championship Series the Indians met another club that had been a perennial loser, one gliding along on the wings of destiny. On August 23 the Seattle Mariners were 54-55 and were a distant third in the AL West, eleven-and-a-half games behind California. Then, while the Angels folded, the Mariners got hot. Seattle went 24-11 down the stretch, caught California, and routed them in a one-game playoff for the West title at the Kingdome. It was the first championship of any kind for the Mariners, their first trip to the postseason- and it arguably saved baseball in the Pacific Northwest.

The Mariners then met the New York Yankees in what could be the greatest Division Series ever. New York grabbed a 2-0 series lead with a pair of wins at Yankee Stadium, including a 15-inning marathon in Game Two. But when the series moved west to the cauldron of noise known as the Kingdome, everything changed. Seattle beat the Yankees 7-4 in Game Three, overcame an early 5-0 deficit to win Game Four 11-8- and then came Game Five. It was a marvelous, eleven-inning drama that ended when Edgar Martinez belted a double to deep left that scored Joey Cora and Ken Griffey Jr. and gave Seattle a come-from-behind 6-5 victory. Edgar’s line shot, Griffey’s all-out sprint from first to home, his safe slide into the plate, the explosion of Mariners onto the field, the screaming din in the Kingdome, are part of Seattle sports lore.

You’d think a club that hadn’t won anything in 41 years would be a natural Cinderella. But that just wasn’t the case. The Mariners had captured the heart of the baseball world- and the swaggering Indians, with their 100 wins and glowering superstar, were cast in the role of the heavy.

But it wasn’t as if Seattle was devoid of talent- far from it. Centerfielder Ken Griffey Jr. was perhaps the most gifted player in the game and he was back healthy after missing a large portion of the season with a broken wrist. Shaven-headed Jay Buhner belted 40 home runs, first baseman Tino Martinez had his breakout year with 31 home runs and 111 RBI and veteran DH Edgar Martinez won the batting title with a lofty .356 average. Edgar had devastated the Yankees in the ALDS, hitting .571, knocking in ten runs and blasting the game-winning grand slam in Game Four and the game-winning double in Game Five. Mound-wise Seattle had the game’s biggest and baddest in 6’10” flamethrower Randy Johnson. The Mariners benefited from the collapse of the Angels, but they were no fluke. They could play.

The grueling series with the Yankees had depleted Seattle’s pitching staff. So Mariners manager Lou Piniella was forced to go with 22-year old rookie Bob Wolcott, who hadn’t even been on the active roster for the ALDS, as his Game One starter. A nervous Wolcott walked the first three batters in the top of the first inning. But he pitched out of the jam, settled down and gave the Mariners seven strong innings. Luis Sojo broke a 2-2 tie with an RBI double in the bottom of the seventh and Seattle hung on to draw first blood, 3-2.

(Due to the vagaries of the playoff system at the time the Indians, despite having the best record in the majors, did not have home-field advantage in any of the three postseason series they played.)

Cleveland bounced back in Game Two behind the bat of Manny Ramirez and the arm of Orel Hershiser. Manny belted a pair of home runs while Hershiser spun eight strong innings for his sixth career postseason win without a loss. The Tribe took Game Two, 5-2, to tie the series as it headed to Jacobs Field for the middle three games.

Finally recovered from his Division-Series exertions, Randy Johnson got the start for Seattle in Game Three against Charles Nagy. The Big Unit had a 2-1 lead in the eighth inning when Cleveland tied the game with an unearned run. But in the top of the eleventh Jay Buhner belted a three-run shot off Eric Plunk to hand Cleveland its first extra-inning loss of the season, and gave the Mariners a 2-1 series lead. Now the Indians were in trouble. They had to win both of the remaining games in Cleveland or face going back to Seattle down 3-2, facing a Mariners team that had won 20 of its previous 24 games in the Kingdome.

The Tribe needed a hero at this critical juncture and they found an unlikely one. Ken Hill had been a mainstay on the pitching staff of the powerful ’94 Expos but had fizzled in St. Louis before being acquired by the Tribe in late July of 1995. He pitched decently down the stretch for Cleveland, going 4-1, and had been the winning pitcher in the 13-inning Division-Series opener, but Game Four of the ALCS would be his first career postseason start. Hill made it a good one, pitching seven shutout innings, while the Tribe battered Seattle starter Andy Benes for six runs in two-and-a-third innings. Cleveland’s 7-0 shutout evened the series- and from here on out the Tribe, or more specifically the Tribe pitchers, would rule the day.

Game Five was the pivotal game of the series, the most dramatic game- and maybe the most nerve-wracking experience I’ve ever had as a Tribe fan. It was Orel Hershiser for the Tribe, Chris Bosio for the Mariners. Both teams must have been nervous too- they combined for six errors, four by the Indians. Cleveland opened the scoring in the bottom of the first when Omar Vizquel reached on an error by Tino Martinez and scored on Eddie Murray’s single. Seattle tied it in the third on Junior Griffey’s RBI double and took a 2-1 lead in the fourth when Albert Belle’s two-out error allowed Joey Cora to score. At my apartment watching the game with several other people, I was dying a thousand deaths. I may have thrown one temper tantrum in every inning that night. I probably didn’t make it a pleasant viewing experience for the others since I was freaking out every five minutes. To this day I watch Indians and Cavaliers playoff games alone. I’m just unbearable to be around during those games.

Cleveland seized a 3-2 lead in the sixth when Eddie Murray doubled and Jim Thome pulled a two-run home run to right. Seattle came right back in the seventh. Dan Wilson opened the frame by reaching on an error by Paul Sorrento and went around to third when Joey Cora was safe on a fielder’s choice. Edgar Martinez- having a horrific series- forced Cora at second, with Wilson holding at third. Now the M’s had men on first and third with one out- and Ken Griffey Jr. and Jay Buhner were on their way to the plate.

Cleveland seized a 3-2 lead in the sixth when Eddie Murray doubled and Jim Thome pulled a two-run home run to right. Seattle came right back in the seventh. Dan Wilson opened the frame by reaching on an error by Paul Sorrento and went around to third when Joey Cora was safe on a fielder’s choice. Edgar Martinez- having a horrific series- forced Cora at second, with Wilson holding at third. Now the M’s had men on first and third with one out- and Ken Griffey Jr. and Jay Buhner were on their way to the plate.

Enter lefty specialist Paul Assenmacher. With his weak chin and salt-and-pepper beard Assenmacher looked more like a postal worker than a baseball player. But he was death on lefties, especially Griffey, who had absolutely no clue how to hit him. Assenmacher struck out Griffey on four pitches. At this point Mike Hargrove rolled the dice and kept Assenmacher in the game to face the right-handed Buhner. Paul promptly struck him out to end the inning with the Indians still out in front, 3-2. It was one of the finest exhibitions of crunch-time pitching in the history of the franchise. One inning later Eric Plunk came up with his own heroics, inducing Luis Sojo to line into a double play with Mariners on first and second and one out.

Cleveland hung on to win, 3-2. Now the Indians were one win away from the World Series. Game Six pitted Randy Johnson against Dennis Martinez- and El Presidente was absolutely heroic. One of the toughest, gutsiest pitchers I’ve ever seen, Martinez handcuffed the Mariners for seven shutout innings. Cleveland broke a scoreless tie in the top of the fifth when Alvaro Espinoza (whom Grover would platoon in place of Jim Thome against lefties, much to my annoyance) reached on a throwing error by Joey Cora and scored on Kenny Lofton’s opposite-field single to left. It was a big hit by Lofton- but the speedster was just getting started.

The Indians were still clinging to their 1-0 lead when they came to bat in the top of the eighth. Tony Pena got things started with a leadoff double off the Big Unit and was replaced by pinch-runner Ruben Amaro. Lofton bunted safely to the right of the mound to advance Amaro to third and then stole second, putting a pair of men in scoring position with no outs. What followed was the sequence of the game- and the series.

Randy Johnson’s first pitch to Omar Vizquel was a rising fastball that got away from catcher Dan Wilson for a passed ball. Amaro scored easily, which was expected. What wasn’t expected was what Lofton did. Never stopping or even slowing down, Kenny flew around third and headed for the plate. A surprised Wilson couldn’t get the ball back to Johnson in time, and Kenny slid in under the tag to make it 3-0 in favor of the Indians.

Seattle still had six outs left. But we knew right then it was over. Kenny Lofton’s second-to-home dash had broken the spirit of the indomitable Mariners. We could see it, especially when Carlos Baerga stroked a solo home run off the stunned Big Unit to make it 4-0. The Indians were going to win the pennant. They were going to the World Series. The final out, Jay Buhner’s ground ball to Espinoza, was a mere formality.

At the end we turned down the sound of the television and turned on the radio. We wanted to hear Herb Score’s call of the final three outs. Mr. Score wasn’t the most polished of broadcasters but he was by all accounts a gentleman, and for those of us who came of age in the ‘80s he was the voice of summer, his faint New York accent a constant presence over the sound of lawnmowers, burgers frying on the grille and kids splashing in the pool. We wanted to hear this man call the pennant-winning play. And he did, in the same calm, unruffled tone he used back in the bad old days when Don “The Rock” Schulze or Rich Yett were knocked out of the box in front of 6,000 at the Stadium. “And the Indians have won the pennant. How about that?”

Then I did what probably a lot of guys did around here. I picked up the phone and called my dad. I just wanted to tell him we’d done it. The warm memory of that call will stay with me forever. (My dad was sleeping when I called. All he said was, “We did? That’s great.”)

And After…

The 1995 Indians didn’t finish their journey with a World Championship. Atlanta’s frontline pitching was too strong and the Braves defeated Cleveland in the World Series, four games to two. At the time I didn’t care. All I’d wanted was to see the Indians in the World Series, and I did. All of the disillusionment- the defections of Belle, Ramirez and Thome, the disappointment of 1997, the frustration of the Shapiro-Wedge era- it lay in the future. In the fall of 1995 the world was young, I was young, and the Indians were going to be powerful forever. And they would have plenty more chances to win the World Championship.

It didn’t work out that way. But even though the dream didn’t quite reach fruition, 1995 is still special. One of these days the Indians might win it all. But I can almost guarantee that club, be it five, ten or a hundred years in the future, won’t hold a candle to 1995. Kenny… Omar… Carlos… AB… Manny… Sandy… Thome… the Bulldog… El Presidente… those names will live forever in my mind as part of the greatest Cleveland team I’ve ever seen.

Hard to believe it’s been fifteen years.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)