Indians Archive

Indians Archive  The Ballad of Jeff Metcalf

The Ballad of Jeff Metcalf

Naturally, a big part of being a baseball fan is holding dear to your favorite players, both those currently playing and those long since departed from the diamond.

Naturally, a big part of being a baseball fan is holding dear to your favorite players, both those currently playing and those long since departed from the diamond.

Bob Feller was an obvious choice for Cleveland fans over the course of his legendary 20-year career. In the 1940s, Boy Manager Lou Boudreau was often the toast of the town. And God help you if you knocked the Rock.

But a few Indians fans - very few, actually - can point to another player as one of their favorites. One whose name never appeared in a box score and whose statistics can’t be found in The Baseball Encyclopedia.

That’s because he doesn’t exist.

Even still, you probably know him.

Maybe to you he’s Coach Eric Taylor in the painfully realistic portrayal of Texas high school football we know as NBC’s Friday Night Lights.

Or perhaps you know him as Gary Hobson, a regular Joe who just happened to receive tomorrow’s newspaper today in CBS’s modestly successful Early Edition in the late 1990s.

Or maybe he’s pompous film actor Bruce Baxter from Peter Jackson’s epic King Kong remake. And come this summer, you’ll almost certainly come to know him as one of the leads in J.J. Abrams’ highly anticipated some-sort-of-alien-breaking-out-of-a-train-and-blowing-a-small-town-all-to-hell blockbuster, Super 8.

He’s handsome, charming, 45-year-old actor Kyle Chandler, who’s managed to put together an impressive acting career over the past two decades despite never leading a project that hit it truly big.

But 20 years ago, if you were one of the lucky 14 or 15 people who faithfully watched a critically acclaimed one-hour historical drama called Homefront on ABC, you know him as Jeff Metcalf, right fielder for the Cleveland Indians.

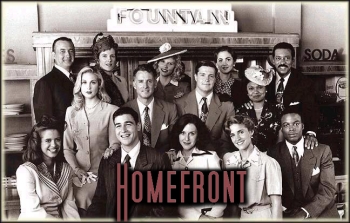

Homefront is one of those shows that, quite honestly, was too good for American television, and subsequently suffered a premature, tragic death. Created by Mentor native Bernard Lechowick and his wife, Lynne Marie Latham, both of whom had helped turn Knots Landing into a primetime success in the ’80s, Homefront told the story of a collection of families in the fictional town of River Run, Ohio, (based loosely on Mentor) immediately following the conclusion of World War II.

It was originally designed as a primetime soap opera akin to Dallas or Falcon Crest, fueled by love triangles and will-they-won’t-they relationships. But Homefront developed into a remarkably accurate, non-saccharine postcard of American life in the late 1940s. While there was just enough Norman Rockwell ambiance and Glenn Miller music in the background to set the mood, its storylines quickly got gritty, focusing on the massive conflict created when a labor union is formed at River Run’s largest factory (a movement led by a charismatic union organizer played by John Slattery, now celebrated as silver-haired Roger Sterling on the impossibly wonderful Mad Men), the hypocrisy and hatred blacks encountered even after honorably serving their country in the war, and the constant frustration of ambitious and intelligent women whose career paths were confined to secretary, waitress, or housewife.

Along the way, mixed in between a terrifying polio outbreak and a red-scare witch hunt, one of the longer story arcs focused on Chandler as young bartender Jeff Metcalf and his quest to play Major League Baseball.

It was a storyline that came – appropriately – out of right field. Jeff had been established as a good-hearted lover of sports who dreamily talked about one day playing professional baseball, but his character wasn’t designed to lead the series.

Then, on a rainy night in February, Jeff returns home after a long shift at the local roadhouse to find a letter addressed to him from the Cleveland Indians.

Unable to believe his own eyes, he hands the letter over to his sister Linda to read.

“Please report to our spring-training facility in Clearwater, Florida,” she says in the darkened kitchen as the rain pounds against the Metcalf house, her voice rising in astonishment. She looks up at her kid brother. “The Indians want you!”

Jeff’s sheepish smile reappears. “I got a shot!” he cries, embracing his sister and whirling her around in a circle.

While it’s unclear exactly how someone watching the show not already enamored with Cleveland or the Indians would have welcomed this development, to the rest of us, this was like standing beneath a broken piñata and being showered with candy.

Over the next several episodes, we watched as Jeff attempted to make his lifelong dream come true, and in the process, the 1946 Cleveland Indians became as real as their modern-day ancestors.

From the very first line introducing the story, you knew this was going to be well done. Clearwater, Florida, was indeed the Indians’ spring-training headquarters in 1946 – but that year and that year only. (And when the Indians switched to Tucson, Arizona, for camp in ’47, Homefront did, too. But we’ll get to that.)

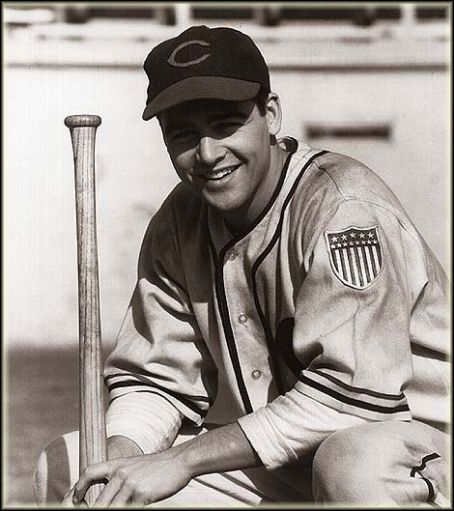

Sure enough, when Jeff takes the field in Clearwater, he’s decked out in full 1940s Indians’ regalia: navy blue cap with red bill and a thick, wool, cream-colored jersey with a red wishbone “C” on the left breast.

And perhaps in an unintended stroke of genius on the part of Homefront’s producers, Jeff receives guidance a lovable old heartbreaker named Coach Zelnick, played by none other than James Gammon – better known as Lou Brown, the Indians’ manager in Major League. The thick moustache is gone, his hair is slicked back, and he’s wearing an older Indians’ uniform, but there’s an immediate connection that made every Indians’ fan fall even further hopelessly in love with this show.

When Jeff struggles during camp, a gorgeous blonde bartender and baseball genius offers sage advice – along with a not-so-subtle invitation for a roll in the hay. Though Jeff is informed by his would-be teammates that the last three players who slept with her all made the team (a tough order, since this was, after all, the one and only time the Indians trained in Clearwater), his decision is complicated – his cute-as-a-button fiancée Ginger is back in River Run faithfully awaiting his return.

Eventually, after an awkward encounter in Jeff’s room when Ginger arrives to surprise him and discovers him in the company of the blonde bartender, he makes the team and returns to Cleveland as a member of the Indians.

Homefront commemorates its version of the 1946 opener with an establishing shot of the Indians’ iconic sign atop Cleveland Stadium depicting Chief Wahoo, leg perched up and about to swing a bat (though, to be fair, that sign wasn’t constructed for another 15 years), and the show’s remaining cast of characters all file into a Los Angeles soundstage designed to be the old park we knew on Lake Erie.

Jeff doesn’t start, but late in the contest, the off-screen voice of manager Lou Boudreau instructs him to step into the on-deck circle as a pinch-hitter with a man on first and one out in the ninth with the Indians down two runs. But with his friends and family anticipating a Hollywood ending, the batter before him grounds into a double play, ending the game before Jeff gets a shot to win it.

Over the next few episodes, Jeff gradually earns more playing time and we often hear his heroics over the radio as other scenes play out. One of the more impressive moments comes as the radio crackles the play-by-play description of Jeff racing around the bases as the workers at the River Run factory silently arm themselves with pipes and chains, anticipating a blitz of police officers crashing through the gates to forcibly end the union’s lock-in after failed contract negotiations.

While certain liberties are taken with the facts (the Chief Wahoo sign, for instance), the writers remained as close to reality as possible – having Jeff and Ginger discuss Bob Feller’s no-hitter against the Yankees that April, then at season’s end, dutifully reporting the ’46 Tribe’s actual win tally of 68. Later, in another storyline, the owner of the River Run factory (played by Dayton native Ken Jenkins – best known as the venerable Dr. Bob Kelso on Scrubs) and Indians’ season-ticket holder enthusiastically follows Bob Feller’s quest to break the all-time single-season strikeout record. (Which he did in Detroit on the last day of the season – encompassed in a train trip that factors into a key Homefront plotline).

By the time Homefront’s second season began in the fall of 1992, Jeff Metcalf was the heart of the show. He’s the Indians’ starting right fielder and is courting an endorsement deal from a cigarette company. He finishes his rookie season hitting .297 (which, in reality, would have been second on the team in ’46) and – after a heart-wrenching breakup with Ginger – joins up with a bunch of fellow ballplayers to barnstorm across the country as The Traveling Lemo Tomato Juice All-Stars.

In typical Cleveland fashion, however, nothing good ever lasts. Jeff is kicked off the tour after several entertaining violations of team rules and injures his knee when he slips on a tomato outside the train station (a symbolic twist of irony too complicated to explain here). Upon returning home, he’s informed by his doctor that his knee didn’t heal properly and his baseball playing days are over.

Story arc completed, we believe.

But not so fast!

With his promising baseball career apparently over as suddenly as it began and the rest of his life slowly spiraling downward, Jeff hobbles through the winter tending bar back at the roadhouse. When the Indians catch wind of his knee injury (this now being 1947, he’d managed to keep it a secret), they force him into a humiliating workout in the snow-covered right-field corner of Cleveland Stadium, after which they pronounce him not even worth the expense of taking to Arizona, their new spring-training home.

Through another of the characters, who’d played in the Negro Leagues, Jeff acquires a bottle of mythical liniment concocted by Satchel Paige, which the savvy pitching legend swore would heal any injury. Gradually, Jeff works his way back to health and eventually earns another shot with the Indians thanks to Coach Zelnick. Jeff tears it up at his “tryout” and on the way home, wins Ginger back from an annoyingly milquetoast teammate.

In the final episode of the series, Jeff is informed that Boudreau was indeed impressed (albeit off-camera), and instructs him to join up with one of the Indians’ farm teams in Wichita, Kansas. (Ironically, the script originally called for Jeff to be sent to Waco, Texas, but that just happened to be the week of the infamous David Koresh/FBI standoff in Waco, calling for an emergency ADR session to voice-over the Homefront reference.)

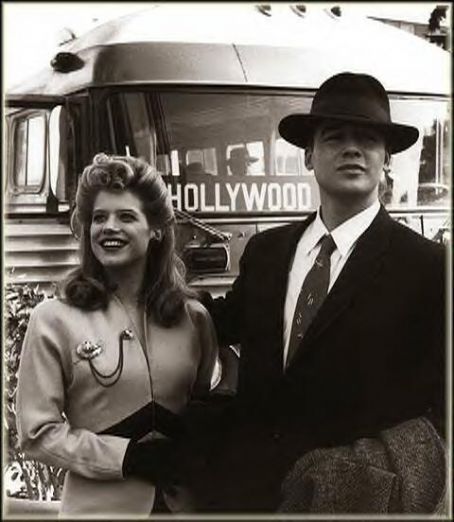

The series ends with Jeff and Ginger getting married in an improvised ceremony as the train for Kansas (or maybe Texas) pulls out of the station, both destined for bigger and brighter things in the future.

Yet we can only wonder. Three weeks later, after bouncing it around all over its schedule in two seasons, ABC officially pulled the plug on Homefront and the Ballad of Jeff Metcalf.

We’re left to ponder if Jeff would have played a key role on the 1948 world-championship team a year later. Or, as history suggests, if he would have been replaced in the outfield by the American League’s first African-American player, Larry Doby. (And what a storyline that would have been, friends and neighbors!)

This fall will mark the 20th anniversary of the premiere of Homefront, and though it still has yet to (and sadly, may never) be released on DVD, it lives fondly in the hearts of the three dozen fans who watched it faithfully each week between September of 1991 and April of 1993.

To those of you who didn’t watch – who may have never heard of River Run or Jeff Metcalf until five minutes ago – I hope you can appreciate how special that little imaginary world was, however short-lived it may have been. It was – in those pre-Jacobs Field days – the first time we’d seen any reference to the Tribe on primetime network television. And it was heartwarming enough to make us smile 20 years later whenever we conjure up the image that that energetic, hopeful young kid getting a chance to play with his – and our – hometown team.

Good night, Jeffrey Metcalf - wherever you are.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)