Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Blast From The Past: Doug Jones

Blast From The Past: Doug Jones

Mariano Rivera: “Super Mariano”. Francisco Rodriguez: “K-Rod”. Mitch Williams: (sing it) “Wild Thing!” (“You-stole-a-Cleve-land thing!”).

Mariano Rivera: “Super Mariano”. Francisco Rodriguez: “K-Rod”. Mitch Williams: (sing it) “Wild Thing!” (“You-stole-a-Cleve-land thing!”).

Doug Jones: “Sultan of Slow”?

Perhaps Doug Jones’ nickname isn’t very widely known, even among Tribe fans. I don’t suspect he would mind terribly. The unassuming, unlikely star closer for the late 1980s Cleveland Indians never was your stereotypical brash and showy big league pitcher.

Major league baseball closers are ‘supposed’ to be powerful and intimidating. They bring the heat. But Doug Jones earned every ounce of respect he has received.

Doug Jones grew up watching his father race sprint cars locally in central Indiana (think narrow roll cages with wheels). When he was old enough, he raced his father’s car in a qualifying race. Talk about fast and powerful: he ran into the wall on the last lap. Jones made the decision to pursue a safe baseball career instead.

Jones pitched for a year in college as a Butler Bulldog, and then transferred to Central Arizona. While there in 1978, he was drafted in the third round by the Milwaukee Brewers. Jones pitched in the Brewers’ minor league system for several seasons. From his comments over the years, his style at that time seems similar to that of thousands of young boys playing in the back yard, or the neighborhood “field” or “empty lot” (an aside to the youngsters: there used to be such things, back in the day). He’d do whatever he thought would ruin the hitters’ timing- vary his windup, throw from every arm angle… His upper-80s fastball wasn’t sufficiently impressive enough for Milwaukee, so they released him in early 1985. Doug Jones’ confidence was down, and he was at the point where legions of young men find themselves every year: at the crossroads of whether to keep trying, or retire from baseball.

Doug Jones could always hit his spots with each of his pitches: curveball, screwball, slider, forkball, knuckleball, and the fastball. Before the Brewers released Jones, he learned to throw a particular brand of changeup from teammate Willie Mueller. Fans of the movie Major League will recall Mueller as New York Yankee reliever, The Duke (and observers of Major League star Charlie Sheen will recall that he apparently invoked the image of The Duke in a recent rant on ‘winning’). The changeup Jones learned from Mueller was not only of a slower speed, but it dipped down and away from left handed hitters (and down and in to righties), like a slow scroogie.

Jones called several teams, asking if he could try out in the Spring of 1985. The Cleveland Indians invited him to Tucson for Spring training, but at his own expense. Jones, who by now was married and himself a father, sold his family car to help pay for his three weeks at Hi Corbett Field. He initially had an ERA of nearly 20.00. Hitters knew he was going to throw strikes, so they began to just go up to the plate hacking. And as Kris Kristofferson wrote, “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” So Jones decided one day to let ‘er rip, throwing nothing but fastballs. He knew he was expected to pitch three innings. For his first inning, he retired the side. He later said he’d broken some bats in the process. But he was completely spent, and knew that when he came back out, he’d have to vary the speed a little to last the outing. So he decided to go with the changeup he’d learned. He breezed through the next two innings. He resolved from then on to forget his other pitches, and only go with his fastball and changeup (and the occasional knuckle curve). In his eighth year of professional baseball, Doug Jones had discovered the formula which one day would make him one of the top closers of his generation.

But the Indians did not yet know what they had. At age 28, after Jones pitched minor league ball for them in 1985, they offered him a position as a minor league pitching instructor. Again at a crossroads. Jones didn’t give up. In 1986 he moved his way up to Triple A, leading his league in ERA. (This may have been around the time he began growing his bushy mustache, which would one day liken him to the manager of the Tribe in Major League). Alas, due to his not being a hard thrower, the Tribe 'thinkers' (irony intended) kept Jones in the minors until the expanded-roster callups in September. This was despite a midseason injury to Cleveland’s regular closer, Ernie Camacho.

Jones had heard manager Pat Corrales was down on him. Corrales was strong-willed and opinionated, and wanted guys who could throw 90+ mph. He wanted no part of a pitcher who threw a “70-miles-an-hour fastball”, as he reportedly referred to Jones’.

Jones had heard manager Pat Corrales was down on him. Corrales was strong-willed and opinionated, and wanted guys who could throw 90+ mph. He wanted no part of a pitcher who threw a “70-miles-an-hour fastball”, as he reportedly referred to Jones’.

Jones’ playing demeanor was very measured and low-keyed. This may have been a reason for Pat Corrales' lack of belief in him. It may also have contributed to the Indians considering him coaching material.

Doug Jones made the Cleveland roster out of Spring training in 1987. After a bit, he was again assigned to the minors. Soon enough, he was brought back up, and ended the year with 8 saves and a 3.15 ERA. He assumed that he’d be guaranteed a roster spot in 1988, but new manager Doc Edwards warned him that he needed to really impress to make the team- new GM Hank Peters was still skeptical of taking Jones north, vs. a couple of young, no-name minor leaguers. Jones needed to out-pitch the rookies on the final day of camp while much of the organization was packing, loading up, and getting ready to make the trip north. So he did.

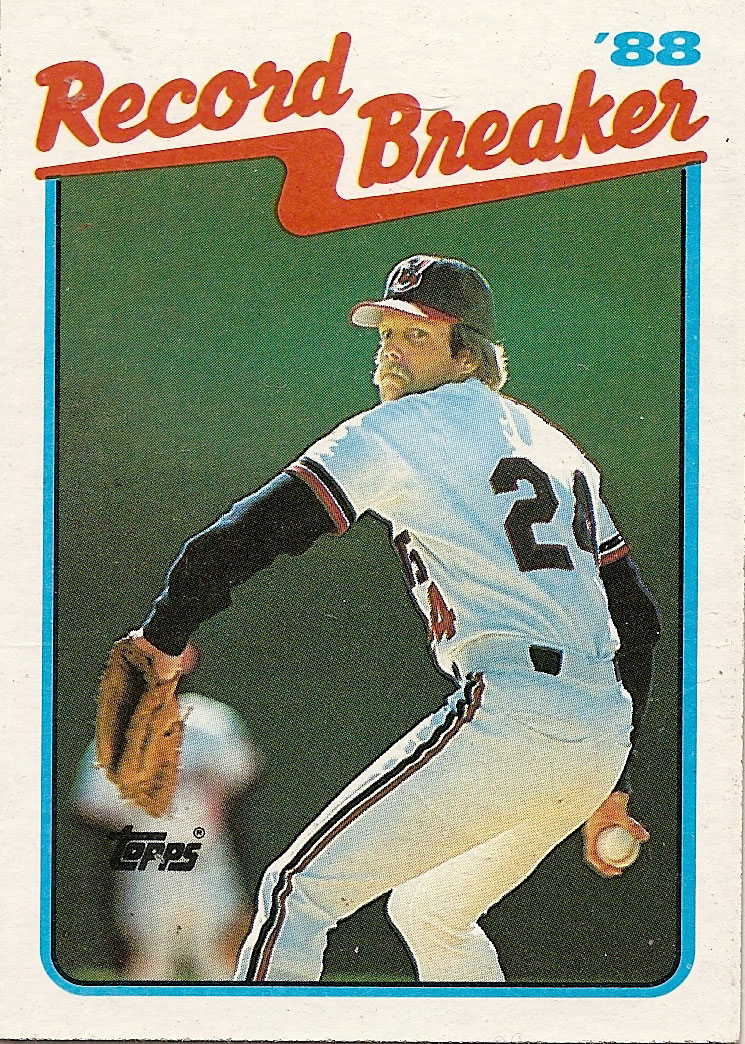

In 1988, Doug Jones became an American League All-Star. True, each team is required to be represented by at least one player, but the league was not doing Jones a favor. The Tribe had other players who were arguably All-Star-worthy in Julio Franco and Joe Carter. Doug Jones had just set the new major league record for consecutive saves, eclipsing the mark of 13 set the year before by Phillie Steve Bedrosian. His 37 saves that year broke the team record of 23, set by Camacho in 1984.

From 1988 to 1990, Doug Jones was an elite closer for the Tribe. He was an All-Star all three years, and his 112 saves during this stretch for a bad Indians team trailed only Dennis Eckersley, who was closing for the American League powerhouse Oakland A’s. Hitters reported they couldn’t hit Jones’ changeup when looking for the fastball, and they couldn’t hit his fastball when looking for the changeup. I recall a quote from Jones from that era, to the effect that it made his pitches look faster when he stuck his chin out during his windup- just prior to releasing the ball. To this day, I have no idea whether he was just messing with a reporter. But as a Tribe fan in my twenties at the time, I can testify that I incorporated some chin-jutting into my Wiffleball windup during lunch hour at work. With success. (Did it make my pitches appear faster? Or did it just get the batter laughing too much? Does it matter?)

In 1991, Doug Jones’s effectiveness waned. Some said it was a result of having thrown too many pitches the previous three seasons. Jones, by then 34 years old, attributed his struggles to not getting enough work. The Indians still stunk. They let him go as a free agent. They thought he was done, and they had young submarine-style reliever Steve Olin ready to step up. Jones signed on with the Houston Astros for 1992, and had perhaps his best season. He saved 36 games, won 11 and had an ERA of 1.85 over 111 innings.

I mean: Yikes. The Tribe lucks out with having a borderline Hall-of-Famer land in their lap. They first try to keep from using him, and then they get rid of him while he is still in his prime. I mean, you’re the 1991 Cleveland Freaking Indians. You just lost One. Hundred. And Five. Games. It was the worst year ever for an organization which has had many to choose from. Your organization is on record as viewing Jones as coaching material. You have several pitchers who need a veteran's steady presence. You have a guy who said he liked Cleveland, and wasn’t looking to leave. Perhaps I just forget the dozens of other ballplayers Cleveland had just like him, busting their doors down to play for the Tribe.

Jones was an All-Star twice after leaving the Indians. His career wound down after his sixth team, post-1991 (including another stint in Milwaukee, who then traded him to the Cleveland Indians of 1998, in the middle of a pennant run).

In retrospect, Doug Jones started a loose string of several quality closers the Tribe has had since the 80s: Jones/Olin (who died in the tragic boating accident during Spring Training in 1993)/Jose Mesa/Mike Jackson/Steve Karsay/Bob Wickman/Joe Borowski/Chris Perez. Ironically, 1994 saw perhaps the best Indians team of my lifetime- and that team had a void at closer.

Doug Jones finished with 303 career saves (placing him 12th all time), including 129 with Cleveland. He far surpassed Ray Narleski’s team record of 53 (although of course the nature and importance of the save evolved, and did not become an official statistic until 1969). Bob Wickman eventually surpassed Jones’ Indians total, but he of course played on a contender and had many save opportunities.

Doug Jones finished with 303 career saves (placing him 12th all time), including 129 with Cleveland. He far surpassed Ray Narleski’s team record of 53 (although of course the nature and importance of the save evolved, and did not become an official statistic until 1969). Bob Wickman eventually surpassed Jones’ Indians total, but he of course played on a contender and had many save opportunities.

Jones retired when released by Oakland in 2000 at age 43. He currently lives in Tucson, where he coached his three sons through high school. He is now an assistant coach for the San Diego Christian College Hawks (fellow coaches there include former Tribesmen Chris Bando and his younger brother Phil). Jones and his wife also run a Christian music recording label, His Heart Music.

Just a solid guy, who’s shown us a solid way to win, at anything you try: ‘slow’ and steady.

** If you know that the Topps '88 Record Breaker card featured at the top of this piece is not Doug Jones, put a gold star on your forehead, and show your mother when you get home. Jones never wore #24 with the Tribe. I believe this is a photo of Rich "Not Ready" Yett. Of course, Yett never wore #24 with the Tribe either- he wore #42. Perhaps this is from a Spring training game?

Next week: Blast From The Past: A Tribe Fan's 1997 Postseason Memories (Just the Good Stuff), Part I

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)