Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Summer of Shadows Excerpt: Opening Day, 1954

Summer of Shadows Excerpt: Opening Day, 1954

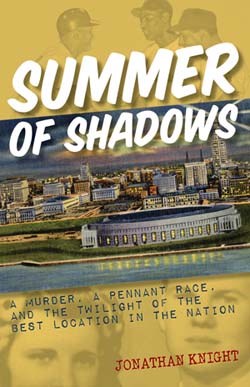

The following is an excerpt from Summer of Shadows: A Murder, a Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation by Jonathan Knight:

The following is an excerpt from Summer of Shadows: A Murder, a Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation by Jonathan Knight:

Clevelanders treated the return of the Indians as a civic holiday, symbolized by the fanfare surrounding the Tribe’s home opener. The Plain Dealer conjectured that there would be many “grandmother’s funerals” that afternoon as the wheels of the workday came to a screeching halt. Fine spring weather added to the atmosphere. As fans streamed into Municipal Stadium, the sky was bright and clear, the memories of a harsh winter long forgotten.

The cost of entry was reasonable, though still considered somewhat pricey by many. A general admission ticket cost $1.25, a spot in the bleachers went for sixty cents. You could splurge for a boxed seat for $2.25. Of course, there were other, less traditional methods of acquiring tickets. With the purchase of a pair of shoes at Garfinkel’s, you’d get a reserved seat ticket for the home opener. And if you were willing to spend $1,727 for a new Chevrolet sedan, you’d receive a ticket to every Indians home night game.

The home ballpark itself was enticing, as Municipal Stadium was widely considered one of the finest places to watch a game. Decades away from the reputation of being a sewage-smelling rathole that attracted swarms of prehistoric insects off the lake, the Stadium in 1954 was a baseball palace – the largest in the nation. During the ’54 team’s first workout at the Stadium, rookie Rudy Regalado hopped up the dugout steps, arched his head around the bowl of the park, and whistled. “Holy cow!” he cried with Jimmy Olsen-like enthusiasm. “This is a big place!”

The 40,000-plus which marched into the ballpark on the lake were treated not just to a gorgeous spring afternoon, but a myriad of improvements to the ballpark. Near Gate A, a new concession area had been constructed that resembled a cafeteria more than a lunch stand. Patrons could walk inside and purchase never-before-available offerings such as hamburgers and fish sandwiches for thirty-five cents apiece. Of course, the stand also offered the usual wares at the usual fares: beer for thirty-five cents, hot dogs for twenty, peanuts for fifteen, and coffee for ten.

The staff selling beverages to fans in their seats also enjoyed a technological breakthrough. Instead of carrying a bulky carton full of bottles, Coca-Cola was placed in portable thermos jugs that were carried via backpack and distributed into cups through a spigot, reducing the number of trips for supplies. On the field, a shiny red Ford convertible would transport pitchers from the bullpen to the pitcher’s mound – quite an upgrade over the Nash Rambler used in previous years.

By the time Ohio Governor Frank Lausche tossed the ceremonial first pitch to Mayor Anthony Celebrezze, the morning chill had burned off and the day had become a portrait of all that an April afternoon in Cleveland could possibly be, a day in which all of the senses were pleasantly teased and tousled. The sky was bright and cloudless, a robin’s eggshell covering all of northeast Ohio. The breeze off the lake still carried some of the sting of winter, but it felt fresh and clean against the skin in contrast to the eager sunshine gradually warmed everything it touched. Wafting through the stadium was the intermingled scent that defined baseball: crushed peanut shells, spilled beer drying on concrete, and everywhere, the pleasant, subtle tang of burning cigarettes.

The ears received the energetic shouts of concessioners and the friendly noodling of the ballpark organ, the only auditory elements that stood out over the low murmur of the excited crowd. In the sunlight, the Indians’ uniforms looked so vibrantly white, textured by the thick wool which comprised them, they almost hurt the eyes to look at. Set against the emerald of the newly grown outfield grass, it was as if color had reappeared after four months of gray skies over an ashen landscape. That afternoon, life returned to Cleveland.

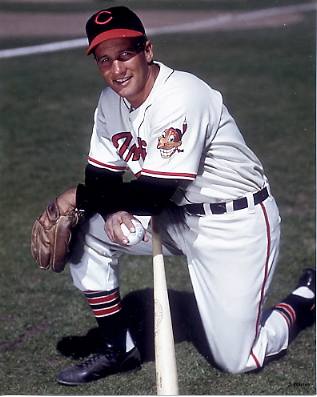

And like the balmy April morning, the Indians began their home opener unusually warm. After Mike Garcia enticed a double play to thwart a Tiger scoring threat in the first, the home team quickly got going when its first two batters walked and advanced on a sacrifice bunt. As Cleveland’s cleanup hitter stepped to the plate, the eager crowd offered an ovation. With his cropped blonde hair peeking out from beneath his batting helmet and his ice-blue eyes leveling on the pitcher, he gripped the bat and flexed his tremendous forearms, which bulged out from his sleeves and somehow made his uniform look smaller than those of his teammates. He was the reigning king of baseball at the peak of his career.

In this moment, he was better than Yogi Berra or Mickey Mantle or Ted Williams. He was what every kid playing in the sandlots of Cleveland aspired to be and who every player clinging to the last thread of his career in the minor leagues looked to for a glimmer of hope. He was Albert Leonard Rosen, who the previous year became the first man to ever receive the Most Valuable Player award by a unanimous vote. In the process, he’d become Cleveland’s first Jewish star athlete.

Now, in his first at-bat in Cleveland in 1954, Rosen pounded a long fly ball to left that brought the runner home from third to give the Indians a 1-0 lead – and, due to an adjustment to the rule book for 1954, with a sacrifice fly, Rosen was charged with a sacrifice fly rather than with an at-bat. Then in the sixth, after Detroit tied the contest, Rosen crushed his first home run of the season to put Cleveland ahead again. The adoring crowd once more showered him with praise. In the All-American town, he was the All-American baseball hero – young, strapping, blonde-haired, blue eyed, and movie-star handsome. And, as it happened, Jewish.

Garcia cruised through the top of the seventh and got the first two Tiger batters in the eighth and the Indians were four outs away from their third straight victory to start the season. But as the Indians came to bat following the stretch, the bright promise of the day began to fade. Storm clouds slid eastward, and the sky over downtown Cleveland gradually transformed from aqua to gunmetal. The sun disappeared, the temperature dropped, and the wind picked up, a steady spring breeze turning into a chilled, blustery nuisance, swirling wrappers and abandoned scorecards around the ballpark.

As the storm moved closer, the Indians’ lead became more precarious. One out away from the ninth, Garcia allowed a single, a stolen base, and another base hit as Detroit tied the contest again. He got out of the inning with no further damage, but the lead was lost in the gathering darkness. At 4:35, the stadium’s lights were turned on – marking the first time they’d ever been used in a home opener. Twenty minutes later, the rain began to fall. It poured down in sheets, drenching the new infield. More symbolically, the rain seemed to rinse away the excitement and hope that began the day like a fresh chalk drawing on a sidewalk. The soothing magic of baseball on opening day vanished as play was halted for ninety minutes as the squall slowly trudged its way along the Lake Erie coastline.

It was nearly 6:30 when the rain passed and the teams returned to the field, the bright blue afternoon sky having transformed to a dark marble of gray and purple. The crowd had dwindled to a fraction of its original size, and the festive holiday mood at the outset had been carried off with the storm. Not surprisingly, Garcia was rusty as the ninth began, walking the first two batters as the Tigers loaded the bases with one out. The winning run came home on a ground out moments later as Detroit managed to take the lead without knocking the ball out of the infield. The Indians went quietly in the ninth and nearly four hours after it began, Cleveland’s 1954 home opener was history.

Over the course of the remaining seventy-six games played on that diamond over the next five months, they would lose only seventeen more times.

Summer of Shadows is available now at amazon.com and bookstores everywhere.

Jonathan Knight will be signing copies of the book at the Crocker Park Barnes & Noble in Westlake on Saturday, April 2 at 2 p.m.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)