Indians Archive

Indians Archive  The Curious Incident of the Tribe in the Night-Time

The Curious Incident of the Tribe in the Night-Time

For me, just as with the Dolans, the Indians started out as a hobby.

I’d followed them casually through my pre-teen years the late ’80s, which was the only way an out-of-town fan could follow his baseball team in those pre-internet, pre-cable-package days. I’d read box scores, watch the two or three games a year that were broadcast on ESPN or WGN, and usually make it up to the old tackle box on the lake once a season.

They weren’t a cause for excitement like the Browns were, but neither were they a source of frustration for me in those formidable years. They were a nice little crossword puzzle to pass the time in the muggy summer months between the time the Cavs flamed out and the Browns started up again.

But something happened the first weekend of May, 1991 to change that.

The Indians rolled their not-quite-.500 show into Oakland to face the mighty Athletics, who had utterly dominated the Tribe since they’d established themselves as the reigning, ’roided-up street toughs of the American League three years earlier with the emergence of Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco. There was no reason to expect this series to go any differently, what with Oakland once gain boasting baseball’s finest record.

Having lost 36 of their last 50 games to the A’s, including the series opener in extra innings on Friday night, the Indians inexplicably went ballistic, scoring 35 runs in the next two days – 20 runs on Saturday and 15 more on Sunday off reigning Cy Young winner Bob Welch. And even better, the second of the two massacres was CBS’s Game of the Week, so I got to experience the bizarre wonder of the Indians taking the team that had won three straight pennants to the woodshed.

I was convinced something had happened that weekend. The Indians, after four straight losing seasons (and about 30 others previous to that I just sort of ignored, the way I’d later react to a high cholesterol reading), had turned a corner.

And to me, it only seemed fair.

In the past eight months, both the usually consistent Browns and Cavaliers had crashed and burned, falling from perennial playoff teams and title contenders to among the worst in their respective leagues. Both drop-offs were startling to me, since I’d never experienced losing seasons following either team, was not accustomed to them, and expected much more.

(With this statement, and with several to follow, you must repeat to yourself the mantra: Well, he was only fourteen.)

So it only seemed natural that it was the Indians’ turn to rise to prominence and fill the void. In my experience of following sports, which dated back to before I’d learned cursive, I’d come to understand that Cleveland was a winning town and couldn’t possibly have all three of its teams suffer at once.

(See above mantra.)

I knew that first weekend in May had symbolized a tectonic shift in Indians’ history. Their carnage in Oakland had pulled them to within a game of .500 and just 3.5 games back of first in the AL East. They were poised to make their move.

(Ibid.)

Their road trip would continue in Seattle on Tuesday night. Floating through that Monday at Ferguson Junior High School, I vowed to listen to the next game on the radio – something I’d never even tried before, since there were about 200 miles between me and C-Town – and witness the Indians take that next step as I took my own, firmly buckling my seat belt on the Tribe bandwagon.

Quick note on my evening routine that eighth-grade year of 1990-91: after winding down by listening to the radio crank out the latest Milli Vanilli and MC Hammer tunes, I’d generally hit the sack between 10 and 11 in order to get enough sleep to be able to wake up when the alarm clock went off like an air-raid siren just before 6 the following morning without going into cardiogenic shock. The first-period bell would ring 90 minutes later, and I’d muddle through the drudgery of another day.

The Indians-Mariners game that night began at 10:35.

I can hear the hissing of air sliding between your clenched teeth as if you were watching the dumb blonde in a horror movie run up the stairs with a psychotic killer on her tail:

Sweet merciful Christ, don’t do it! What are you thinking?! It’s the Indians! They’ve been disappointing their fans since before your dad was your age. This will cause you nothing but pain – deep, rich, honky-tonk jukebox pain.

But even if there had been someone wiser and more experienced there to tell me these things, I was not going be dissuaded.

These Indians had yet to truly let me down. This was a new book, and the 1991 Indians and I were going to write it together.

(All together now: Well, he was only fourteen.)

So just before 10:30 that Tuesday night, right around the time I’d ordinarily flip off the radio in the middle of a Wilson Phillips song, I instead cranked the dial as close as I could to 1100, and sure enough, like a sign from heaven that this cool spring night was ordained as my own, there was Herb Score’s voice beaming into my bedroom like a shimmering beacon of truth. I had indeed found the signal some 200 miles distant and settled in for an evening in the auditory cocoon of baseball on the radio.

Instantly I liked the pitching matchup: the grand poobah of the knuckleball, Tom Candiotti, going for the Tribe and some unknown putz named Randy Johnson toeing the rubber for Seattle. Candiotti got out of some jams early, yet even these didn’t concern me because I knew, after The Weekend of 35 Runs (as it would come to be known), that the Indians were the latest rendition of the Big Red Machine, capable of scoring 10 runs off any damned pitcher who dared stand in their way.

(Well, he was only fourt…No, screw that. That’s just pure silliness at any age.)

And sure enough, after this Johnson schlub held the Indians scoreless in the first three frames,the Tribe came alive, scoring two runs in each the fourth and fifth innings – including a two-out RBI double by a rookie outfielder named Albert (or was it Joey?) Belle, who was four days away from playing a friendly game of ball-tag with a fan at Cleveland Stadium.

By the end of the sixth, it was 6-1 Tribe and inching past midnight. In the darkness of my room, with the spring moon casting long shadows across the brown carpet, I allowed myself to soak in the reality that everything was unfolding just as I’d expected. The Tribe had indeed turned a corner, and I was along for the ride. Yet the exhilaration of being able to listen to the Indians in my own room was beginning to wear off, replaced by a satisfied late-night fatigue. The yawns became longer in the seventh inning and my eyes were constantly watery. But I knew I had enough left in the tank to see it through and refused to allow myself to fall asleep. I’d come this far and I was going to taste victory with the Tribe.

The Mariners scored a cheap run in the eighth when their punch-and-judy shortstop – Omar Vizquel, I think his name was – blooped a single to center off reliever Jesse Orosco. It didn’t matter, I told myself between yawns, particularly after Orosco got out of the inning with no further damage. Three more outs and I could finally release the doorstop keeping up my eyelids - which by now each weighed about 17 pounds.

Thankfully, the Indians went quickly in the ninth facing a young Seattle reliever named Mike Jackson (yup, that Mike Jackson). As we went to the bottom of the ninth, I climbed into bed and pulled the blanket up to my pimple-covered chin. Three quick outs and I could fall asleep contented with a truly enjoyable evening. Heck, maybe I could even do this tomorrow night.

Then Jesse Orosco went and made me hate him. Three of his first five pitches were laced for singles and suddenly the damned bases were loaded with nobody out and the tying damned run was coming to the damned plate. (I should also mention this was the moment I realized that even at fourteen I had a tendency to swear like a drunken sailor when I got truly tired or pissy. The only problem was I hadn’t really sworn enough in my life yet to know how to use the expletives correctly.)

No-no-no-no-no, I thought. There’s no way in the damn hell. They’re not going to blow this. I’ve stayed up all the son of a bitch night for this!

But it was okay. Herb Score informed me that Tribe manager John McNamara had just called for closer Doug Jones to put out this brush fire that dumb-ass Orosco had just started. What a dick.

I began to relax again. The Indians were still up four bastard runs. Even if all the baserunners managed to score, the Indians would still be ahead, and Doug Jones was an out machine. His thick, bushy mustache was like the Maginot Line. He’d racked up 43 saves the year before, and somebody capable of 43 saves could never blow a four-run lead. In my vast five years of experience following the game, I knew that baseball just didn’t work that way.

And sure enough, DJ and his rhapsodic facial hair whiffed Jay Buhner swinging for the first out. I sighed with relief. It was going to be all right.

Now resting my eyes between pitches, that next at-bat lasted 49 years. Edgar Martinez kept fouling off pitches as if he were getting commission on each one. I implored Doug Jones to just let him hit the ball somewhere. Even if it was a deep fly ball, it would only score one run. Just get this crap thing over with.

Then Martinez did indeed hit a deep fly ball to left as I’d hoped, but there was nobody there to catch it. With the miniscule crowd at the Kingdome now roaring like water running into a bathtub, it bounced off the God-damned wall for a God-damned bases-clearing double.

Now it was 6-5 and I was wide awake again.

Oh, no, you fuckers...no way.

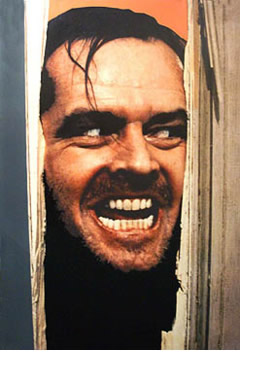

I’d now stayed up later than I had on any night of my life except for a sleepover in a pop-up camper parked in somebody’s front yard the summer between fourth and fifth grade. I was both deliriously tired and as wide awake as if I’d just OD’d on Lik-M-Aid. There was no way I was going to get to sleep for at least another hour, maybe longer. I was starting to see colorful shapes in the darkness and hear the voices of cartoon characters from under the bed.

And if I’d come all this way just so you assholes could blow it in the ninth...

Crackling with nervous tension I’d not felt since the Browns were good 16 long months before, I frantically crawled out of bed and lay prostrate on the floor, pressing my head right against the speaker. My heart rattled my ribcage and I was tasting metal. Each breath I took sounded like a high-pressure sprinkler spitting water across the lawn.

The next batter was Pete O’Brien, who, Herb Score had explained earlier, had played briefly and not terribly well for the Indians two years before.

If he couldn’t cut it with the old Indians, the pre-Weekend of 35 Runs Indians, he sure won’t do anything here, I frantically told myself, but the desperation was beginning to show. I couldn’t take much more of this.

It was as if Doug Jones knew it.

O’Brien cracked his former teammate’s second pitch down the right-field line. I could tell from Herb Score’s tone and from the rise of the crowd that this was bad news.

Holy crap, I thought. These fuckers just tied the game.

But I was wrong. They hadn’t tied it.

It was gone.

Home run and ballgame.

It was 1:37 a.m., and thus began my first real psychological breakdown.

Fueled by anger and immeasurable over-tiredness, I thrust the off switch  on the radio so hard it left a red imprint on my thumb and never really worked right again. I grabbed the radio in my hands – this lying, electronic demon that had betrayed me – and squeezed it manically, either out of frustration or because in my hallucinatory condition I actually thought it was Doug Jones.

on the radio so hard it left a red imprint on my thumb and never really worked right again. I grabbed the radio in my hands – this lying, electronic demon that had betrayed me – and squeezed it manically, either out of frustration or because in my hallucinatory condition I actually thought it was Doug Jones.

I gnarled my face into the carpet and quietly moaned like a dog who’d just got his nose stupidly slammed in a screen door.

I’d been through The Drive and The Fumble and The Shot, all of which had been truly shocking. But the primary emotion in the moments following those debacles was sadness.

This one was rage.

I hated Doug Jones. I hated Doug Jones’ truck-driver mustache. I hated that sick twist Jesse Orosco. My hatred for Pete O’Brien could have operated a blast furnace for six weeks. CBS was the minion of Satan for broadcasting the game on Sunday and getting me all ensorcelled with these idiots. I hated Herb Score for letting this happen and then having the nerve to tell me about it when it did. And I hated the Indians for doing this to me after I’d believed in them and pissed on every morsel of common sense to stay up and listened to this game.

Most of all, I hated myself because now I realized I was smarter than this. I had been rudely introduced to the real world of Cleveland Indians baseball, tricked into thinking it was something other than a rendering plant of misery, and now knew there was no escape. It was like being trapped in an episode The Twilight Zone.

I defiantly threw myself back into bed, trying to tell myself I could thwart my rage and just go to sleep...then have no problem waking up in four hours and going through an entire day of school.

Oh, shit. School.

In my mind, the forthcoming day unfolded like a death-row inmate envisioning his execution the night before. There would be English and Spanish and algebra (oh my hell...how was I going to get through algebra?) and then after lunch somehow try to survive 45 minutes of Earth Science, which was a tall order even when you got more sleep than a meth addict freebasing No-Doz.

Eventually I either fell asleep or knocked myself unconscious with my own fists. I don’t remember how long it took me to calm down – maybe I still haven’t. And somehow I got through that next day of school operating on just over three hours of sleep.

But it took years for me to get over the events of that night. Come to think of it, as the 20th anniversary approaches, I still don’t think I’m completely over it.

To this day, I have a phobia about those late-night games. And any ninth inning in which the Indians have the lead, for that matter.

And that didn’t happen a lot over the next five months of that 1991 season.

The Indians never again were that close to .500. The horror in Seattle that night was the first in a string of eight losses in nine games and by the Fourth of July they were 27 games under .500. They would go on to lose a total of 105 and forever etch themselves in Tribe history as the worst squad the franchise ever fielded.

The 1991 Indians sucked in ways scientists are only beginning to comprehend, but to this day I’m convinced that the season turned into full-blown Amityville that night (or for me, early morning). I still believe that had they won that night, had they closed out the Mariners instead of blowing a five-run lead with four outs to go, that season would have unfolded very differently.

Clearly, my fantasies about the Indians suddenly becoming a playoff-caliber club after what had happened during The Weekend of 35 Runs were just that – fantasies. And yet, they’d shown signs over that first month of the season that they were a bona fide .500 team, not one that would lose 105 games.

But as that last inning played out in the wee hours of the morning, they became a team that would lose 105 games.

So as it happened, I got my wish - I did witness history that night. Two doses of it, actually. Not only did I experience the moment one of the most mortifying teams in baseball history crawled out of its slimy birth canal, but also the moment the Indians stopped being a hobby and became a part of me.

I knew that night, just as I know now, that following the Indians would be my destiny because they, too, had it in them to get me wildly excited and then obliterate my hopes and dreams just as the Browns and Cavaliers had before them.

And only true love can deliver misery like that.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)