Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Summer of Shadows Excerpt: The Yankee Doubleheader

Summer of Shadows Excerpt: The Yankee Doubleheader

The following is an excerpt from Summer of Shadows: A Murder, a Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation by Jonathan Knight.

The following is an excerpt from Summer of Shadows: A Murder, a Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation by Jonathan Knight.

The sun rose in Cleveland that Sunday at 7:04 a.m. Usually this mundane occurrence went unnoticed, but on this day, the bright, cloudless dawn foreshadowed history. Sunshine gradually crept across the landscape, stretching long shadows across front lawns and living room carpets, and in those shafts of light, the Indians front office saw the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

After a week of conjecture and prognostication, the morning light warmed the chill off a crisp Saturday night and informed Greater Cleveland that yes, the weather would indeed cooperate. Team officials knew the crowd for the doubleheader would top 70,000 no matter what the conditions, but if September 12 turned out to be one of those shimmering days that straddled between summer and fall, even more fans would be drawn to Municipal Stadium.

And sure enough, at nine a.m., with the temperature creeping into the sixties, fans wearing light topcoats and hats began descending on the mammoth ballpark to snatch up the 20,000 bleacher and standing-room seats that remained at sixty cents and $1.25 apiece, respectively.

By the time the gates opened at 10:30, the remaining stockpile of tickets had been picked clean. Indians publicist Nate Wallack admitted he’d never seen such demand for tickets for a single date. Even Tris Speaker, the Hall of Fame center fielder who had managed the Indians to the 1920 world title and remained a franchise emissary, was affected by the demand. Though he’d spent much of the summer in the hospital recovering from heart ailments, he’d still been barraged with requests for tickets for the event that simply came to be referred to as “the Yankee Doubleheader.”

The city, too, was prepared for the onslaught. Every downtown hotel was filled to capacity and parking lots were already jammed. The traffic commissioner assigned 115 officers to help direct cars and control busy intersections, and, starting in the seventh inning of the second game, East Ninth Street would revert to one-way traffic going south between Lakeside and Carnegie and would remain so until all the stadium lots were empty.

The Cleveland Transit System provided “Baseball Specials,” trains running downtown from the suburbs every few minutes. Nineteen specially designated trains consisting of more than 300 cars would bring fans from all around Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, some from as far as Niagara Falls.

For those driving to the game, parking would come at a premium. Parking was prohibited along all main roads downtown, and police were quick to enforce, issuing hundreds of tickets and authorizing the towing of dozens of cars. Many drivers who found empty spots in private lots discovered a new problem. Since many of the smaller lots weren’t operated full-time, their owners weren’t required to register with the city and obtain a license. As a result, they weren’t held to the city’s price guidelines and could charge whatever they wanted. Many motorists were outraged when they discovered they’d have to pay upward of $1.50 to park their cars.

Inside the ballpark, concessioners were ready. Employees of the team’s vending company had worked until one a.m. preparing the thirty-five refreshment booths with necessary supplies. Before the day was over, they would sell more than five tons of hot dogs and roughly 100,000 bottles of beer. And with the afternoon slated to be cool on the lake, the stands were primed with steaming coffee and hot chocolate.

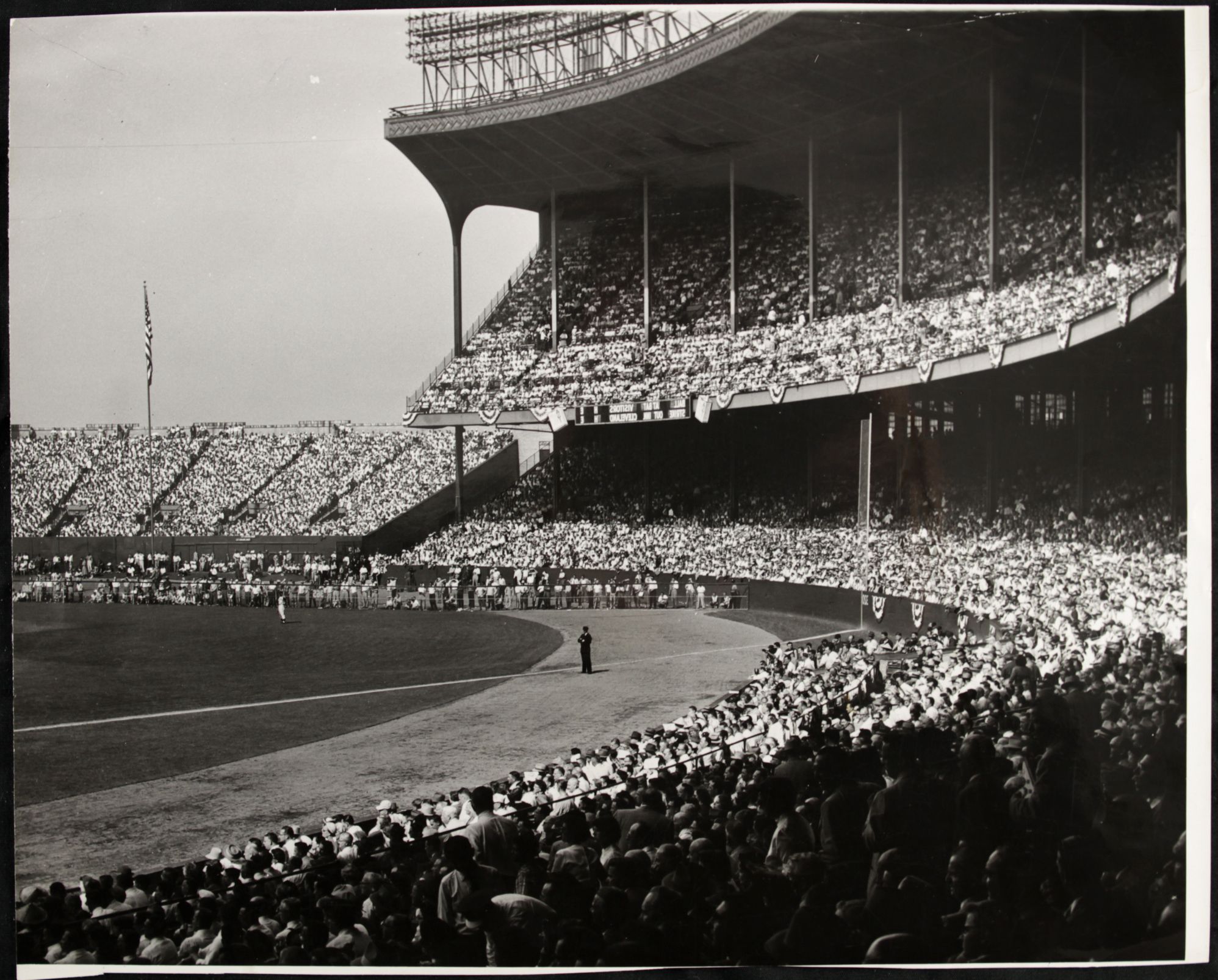

And for many fans, the doubleheader became a daylong experience. By 11:30, one hour after the gates opened and two hours before game time, the standing room area behind the outfield fence was completely filled with more than 10,000 fans. Latecomers were forced to look elsewhere for real estate, and many resorted to sitting on concourse guardrails and hunching down on sloping ramps. Even those fans lucky enough to find prime standing room were lucky if they could see half the field. The tight quarters—and record sales of beer—ultimately led to several fistfights breaking out. Before a single player took the field, tension pulsed through Municipal Stadium.

Even those who didn’t have tickets woke up with a mixture of excitement and unease. The Plain Dealer addressed the pulse of the city that morning with an editorial aptly titled “Relax.”

“Tense this morning?

“Feel a bit more on edge than usual, especially for a Sunday?

“Has breakfast tasted a little less palatable than usual, the voices of those around you a bit more grating? Has the neighbor’s dog been barking louder than you’ve heard him?”

Readers nodded their heads in silent agreement. Some even wondered if the barking dog might have been a gentle nod to the Sheppard’s dog Kokie and his well-documented silence the morning of July 4.

“Relax,” the article continued, “at least until 1:30 this afternoon. It’s just that you’re on the edge on D-H Day, a common affliction.

“For the old nerves are just achieving a fine stage of balance and responsiveness in anticipation of this afternoon’s doubleheader between the Indians and the Yankees.

“Good luck and may the better team win at least one. Indian rooters think they know without a doubt which team that is.”

Yet for all their confidence in their ballclub, Indians fans couldn’t forget that this scenario was eerily reminiscent of past disappointments. Two years before, better than 73,000 packed into Municipal Stadium on the second Sunday in September expecting to cheer the Indians to a victory over New York that would pull them within a half-game of the Yankees. Instead, Casey’s crew blitzed the Tribe 7-1 behind Eddie Lopat and cruised to the pennant.

The year before that, the Indians traveled to New York in mid-September for a Sunday afternoon showdown with a one-game lead. With 68,000 packed into Yankee Stadium, the home team won, 5-1, to pull into a tie, then won the next day as well, again behind Lopat, and took over first for good. The lead may have been greater on this September Sunday, but the Indians were battling history, not just the Yankees.

With thermometers holding steady at sixty-five degrees at noon, fans continued to flood downtown, strolling through the busy streets and stopping in restaurants and hotels, “giving the city the air of a Midwest college town on a Saturday afternoon.” Those without tickets were now turned away—all seats had been sold and all standing-room corrals had been filled. Most fans remained outside the stadium, basking in the glow that emanated from within.

Some grumbled about Hank Greenberg’s stubborn refusal to televise the games. He’d been offered $60,000 for a national telecast but turned it down. Then when Mayor Celebrezze phoned to ask him to televise the games locally, Greenberg once again offered his regrets. He explained that the “complications involved would be insurmountable” but more importantly, the team had promised the fans the previous winter that no home games would be televised, and Greenberg felt he owed it to the fans to keep his word.

Thus, most fans flipped on radios to hear the play-by-play. Yet even Jimmy Dudley’s descriptions couldn’t capture the majesty of the scene as game time approached. It was a baseball sonnet: beneath a shimmering blue sky, a gentle breeze, and the narrow condensed heat of the autumn sun, the largest ballpark in the nation was filled to capacity and the sport’s two finest teams gathered to showcase the game for the world.

When the final tally was conducted, stadium officials couldn’t believe their eyes. For all their optimism, they never expected this. At 1:30 p.m., as Bob Lemon prepared to throw the first pitch to Gil McDougald, 86,563 fans watched and waited—the largest crowd ever to attend a game in the history of baseball.

The one-day total represented more than 10 percent of the 823,000 fans who had attended the twenty-two Indians-Yankees games of 1954, a number that topped the overall season attendance of six major-league teams. In the final, breathless moments before Lemon’s first pitch, Hank Greenberg leaned forward in his seat in his private box and studied the gargantuan gathering with a dark intensity.

Whatever happened next, it would be remembered in this town forever.

Summer of Shadows is now available at amazon.com and bookstores everywhere.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)