Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Blast From The Past: Frankie Pytlak. "That's a Good Czech Name, You Know."

Blast From The Past: Frankie Pytlak. "That's a Good Czech Name, You Know."

He commonly was shirtless while grilling chicken in the backyard with my dad. Not that it mattered, but the effect was natural; one wouldn’t really notice. My barrel-chested grandfather had the deep, permanent tan of a man who’d spent a lifetime of summers out in the Ohio sun.

He commonly was shirtless while grilling chicken in the backyard with my dad. Not that it mattered, but the effect was natural; one wouldn’t really notice. My barrel-chested grandfather had the deep, permanent tan of a man who’d spent a lifetime of summers out in the Ohio sun.

His hands were toughened from working the Geauga County farm for his disabled father. And then later in his Willoughby auto shop right next to Ohio Rubber, on Vine Street; business was good for the bright, self-taught mechanic who’d also been a factory worker in the 1940s during the war.

What drew others to him was his outgoing manner, and his one-liners. Of course, he likely ramped that up when grandchildren were around to provide the laugh track. An example was when a waitress- a perfect stranger- would seat us at a table. She’d introduce herself, and he’d smile and ask, “Do you still love me?” Typically, the waitress would ‘get it’ within a couple seconds and reply, “Of course I do.” And my grandmother would offer a lighthearted smirk.

His grown children enjoyed his humor as much as anyone. They’d often share a childlike laugh with Frank (as even some of them called him occasionally). Like the time they took him to Spencer Gifts at Great Lakes Mall in the 70s. Sampling the silly (and salty) novelties, one of them picked up a ‘lighter’, which actually delivered an electric shock as a practical joke. They took turns trying it out, and it stunned each of them enough to drop the toy. When Frank gave it a squeeze, it buzzed for several seconds as he wondered what the purpose was- his hands were too calloused to register the shock!

As Frank and my father grilled chicken together, they'd often squirt it with a spray bottle (Dad said the bottle contained only water, but the chicken always tasted way too good for that to be true). Every so often, Frank would reach into a pocket and produce a transistor radio. AM radio was a mainstay from his days back at the auto shop, and he would use it to keep track of how the Cleveland Indians game was going that day.

Frank’s pensive moments while the radio was out betrayed his emotional investment in the Tribe. He’d known some glory days, but by the 70s and 80s, the franchise was so horrible that they didn’t even seem to belong in the same league as the contenders. He didn’t dwell on the negative, but he didn’t fool himself either. Sometimes he’d comment on a player. Like the 5’4” Kansas City Royals shortstop at the time. “Patek- Freddie Patek. That’s a good Czech name.” Just like ours. “Frankie Pytlak was a Czech player for the Indians. One time, he caught a baseball thrown from the top of the Terminal Tower.”

Wait-what? He did? What’s the story there?

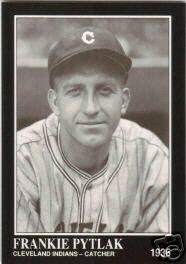

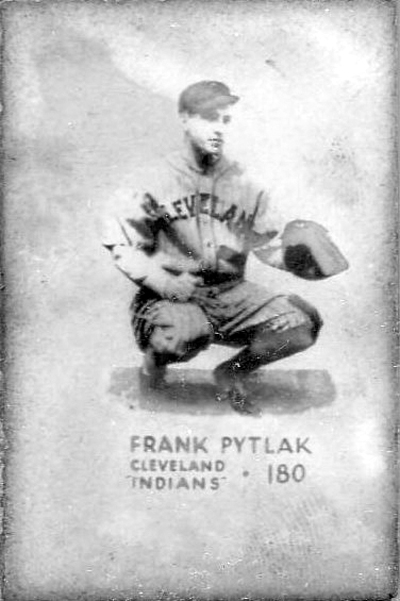

Pytlak was a regular Indians catcher through part of the 1930s. It was during a period in between the fine careers of two all-timers at that position for the Tribe: Luke Sewell in the 1920s, and Jim Hegan in the 1940s and 1950s. At the time of Pytlak’s career, every American was well-versed in the legend of Gabby Street (Walter Johnson‘s Washington Senators catcher): in 1908, Street had caught a ball dropped from the top of the Washington Monument (another catcher performed the feat in 1910). Details of the 555’ catch were shared by tour guides for decades.

Pytlak was a regular Indians catcher through part of the 1930s. It was during a period in between the fine careers of two all-timers at that position for the Tribe: Luke Sewell in the 1920s, and Jim Hegan in the 1940s and 1950s. At the time of Pytlak’s career, every American was well-versed in the legend of Gabby Street (Walter Johnson‘s Washington Senators catcher): in 1908, Street had caught a ball dropped from the top of the Washington Monument (another catcher performed the feat in 1910). Details of the 555’ catch were shared by tour guides for decades.

You know those crazy Americans of the 20th Century- they were always attempting death-defying feats of daring and skill. Stunt pilots. Niagara Falls barrel riders. Karl Wallenda. Evel Knievel.

And catching baseballs from dizzying heights. A copycat effort in 1915 combined a catch with the novelty of flight- and Florida advertising: during spring training in Daytona Beach, pilot Ruth Laws flew at about 500 feet. A grapefruit was tossed out of the plane, and a Brooklyn team’s manager attempted to catch it. He had been expecting a baseball, and when it hit his glove, it glanced off and smacked into his chest. He was knocked to the ground, and was screaming that the ball had split him open. He thought he was bleeding to death- but the ‘blood’ was the juice from the grapefruit, which had splattered all over him!

By the late 1930s, Cleveland had redeveloped the southwest portion of Public Square. Real estate and railroad moguls O.P and M.J. Van Swearingen had spearheaded the construction of the Terminal Tower complex. This was their second hugely successful real estate venture; they previously had completed one of the first planned suburban areas in the U.S.- Shaker Heights, including Shaker Square. Unfortunately for them, the stock market crash of 1929 destroyed their financial empire.

In 1938, there was a precursor to the Greater Cleveland Growth Association: the Come to Cleveland Committee. They had a brilliant idea to promote Cleveland and Terminal Tower- the tallest building between New York and Chicago. The plan was to have balls caught from the top of the 708’, 52-story building.

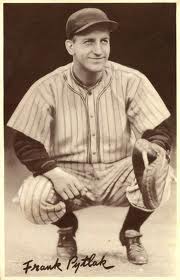

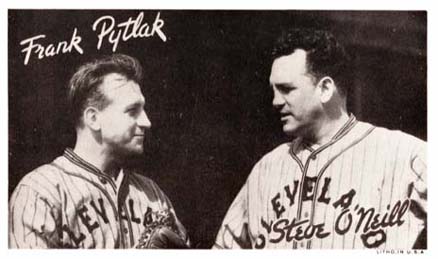

A crowd of ten thousand was said to have attended the August 20 stunt. Dressed in street clothes and steel helmets, five Indians were gathered to attempt the world record: Frank Pytlak, fellow catchers Rollie Hemsley and rookie Henry Helf, and coaches Wally Schang and Johnny Bassler. Dropping the balls from the building was to be performed by another rookie, notable Tribe third baseman Kenny Keltner.

Keltner later said that while he was aiming for the circle drawn on the ground, he could hardly see it. To those on the ground, the balls were barely visible when released- and on their way down, they stopped spinning and instead fluttered as 138mph knuckleballs (the speed was estimated by engineers). The onlookers watched three balls fall to the street. (I’m almost embarrassed to state this, out of disbelief- but one account referred to a ball bouncing 13 stories after hitting the pavement. A police officer was said to have retrieved the ball after the third bounce.) Most accounts are that the uncaught balls bounced 6 stories high. Helf made the first catch, and Pytlak caught one three tries after that.

Keltner later said that while he was aiming for the circle drawn on the ground, he could hardly see it. To those on the ground, the balls were barely visible when released- and on their way down, they stopped spinning and instead fluttered as 138mph knuckleballs (the speed was estimated by engineers). The onlookers watched three balls fall to the street. (I’m almost embarrassed to state this, out of disbelief- but one account referred to a ball bouncing 13 stories after hitting the pavement. A police officer was said to have retrieved the ball after the third bounce.) Most accounts are that the uncaught balls bounced 6 stories high. Helf made the first catch, and Pytlak caught one three tries after that.

Later that day, the Indians played a game at League Park (the Tribe split its home games between League Park and the Stadium during that time). In front of an announced crowd of an even 2,500 (hopefully, the stunt worked better for the city than it did for the Indians), Mel Harder won #11. Frank Pytlak did not play; Hemsley caught Harder that day.

Of course, Pytlak’s and Helf’s record was a target for others to beat. These imitators’ efforts culminated in a 1000’ baseball drop from a Goodyear blimp, in San Francisco. The unfortunate catcher failed to see one of the falling baseballs, and got nailed in the mouth. Reportedly, his jaw shattered; he lost six teeth, and he spent two months in the hospital. That effectively ended interest in future baseball drops.

Frankie Pytlak had a solid baseball career, mostly with Cleveland. He was short in stature, but had a lot of success in fielding percentage and in throwing out base stealers. He even stole 16 bases himself, in 1937. He was known for hitting line drives off the 290ft right field wall at League Park. He also was the catcher when Bob Feller struck out a record 18 batters, on the last day of the 1938 season (the Indians lost; Tigers pitcher Harry Eisenstat carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning until Pytlak hit a curveball for a single).

He was a character, as well. One year, he bought a dictionary and used the longest words he could find in his lengthy letters written to ownership, asking for a pay raise (it eventually worked- he wore the owner down). He once married a girl from his hometown of Buffalo- when the marriage failed, it was said he haphazardly chopped off his hair- so as not to be attractive to girls. He reportedly chided a teammate after a collision while trying to catch a popup- saying, “Didn’t you hear me wave?“ Pytlak had a rivalry with fellow catcher Hemsley; Bob Feller used Hemsley as his preferred catcher by 1938. When Pytlak was injured in 1939, Hemsley became the Tribe’s number one catcher (although Johnny Allen still insisted that Pytlak be his personal catcher).

He was a character, as well. One year, he bought a dictionary and used the longest words he could find in his lengthy letters written to ownership, asking for a pay raise (it eventually worked- he wore the owner down). He once married a girl from his hometown of Buffalo- when the marriage failed, it was said he haphazardly chopped off his hair- so as not to be attractive to girls. He reportedly chided a teammate after a collision while trying to catch a popup- saying, “Didn’t you hear me wave?“ Pytlak had a rivalry with fellow catcher Hemsley; Bob Feller used Hemsley as his preferred catcher by 1938. When Pytlak was injured in 1939, Hemsley became the Tribe’s number one catcher (although Johnny Allen still insisted that Pytlak be his personal catcher).

Pytlak was traded to the Boston Red Sox in 1941. The war had come to the U.S., and he expected to be drafted- so he joined the athletic division of the U.S. Navy at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago and played ball there for a time. (This was where Paul Brown arrived to coach in 1944, after having run the football program at The Ohio State University. It is where he was when team owner Mickey McBride enticed him to become coach of the new Cleveland pro football franchise).

Pytlak was traded to the Boston Red Sox in 1941. The war had come to the U.S., and he expected to be drafted- so he joined the athletic division of the U.S. Navy at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago and played ball there for a time. (This was where Paul Brown arrived to coach in 1944, after having run the football program at The Ohio State University. It is where he was when team owner Mickey McBride enticed him to become coach of the new Cleveland pro football franchise).

Upon his retirement from baseball, Frank Pytlak returned to his beloved Buffalo. He worked at Fischer Sporting Goods for a time, and was a proponent of physical fitness. Quick note on the owner of the sporting goods chain, Dick Fischer: He was also a pro baseball scout, and once was encouraged by an Indianapolis Clowns (Negro Leagues) pitcher to come and watch Henry Aaron play. Fischer, who was working for the Pittsburgh Pirates (and the man who'd signed Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey), watched Aaron spray the ball to all fields during a double header. He came away less than impressed- apparently, he had wanted to see Aaron pull the ball more. It is said that the real race to sign Aaron was between the Milwaukee Braves and the New York Giants anyway. And after already having let Willie Mays slip away, the Braves weren’t going to allow lightning to strike twice.

Kind of a neat figure from the 30s. The guy who caught balls dropped from the Terminal Tower. Frankie Pytlak. And that’s a good Czech name, you know.

Thank you for reading. Next week: Blast From The Past: Dennis Eckersley and the Cleveland Indians: An Ugly Duckling Story.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)