Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Blast From The Past: Vic Power: An All-Time Tribe First Baseman

Blast From The Past: Vic Power: An All-Time Tribe First Baseman

The story has been shared from time to time by ex-Tribe pitcher and broadcaster Jim “Mudcat” Grant. He and Cleveland Indians roommate Vic Power were soaking in the Cooperstown environs. The Indians were about to play their Hall of Fame exhibition ballgame, and the two players noticed the presence of legendary hitter Ty Cobb. They knew of his reputation as a racist, but hey- this was Ty Cobb. An all-time ballplayer. They wanted to meet him. They approached Cobb and Power introduced the pair. The Georgia Peach looked at them and replied, “Hey, how are you two n----- boys doing?” This enraged Power, who began screaming at Cobb. As Mudcat tells it, Cobb was soon seen trying to slip out of the stadium.

The story has been shared from time to time by ex-Tribe pitcher and broadcaster Jim “Mudcat” Grant. He and Cleveland Indians roommate Vic Power were soaking in the Cooperstown environs. The Indians were about to play their Hall of Fame exhibition ballgame, and the two players noticed the presence of legendary hitter Ty Cobb. They knew of his reputation as a racist, but hey- this was Ty Cobb. An all-time ballplayer. They wanted to meet him. They approached Cobb and Power introduced the pair. The Georgia Peach looked at them and replied, “Hey, how are you two n----- boys doing?” This enraged Power, who began screaming at Cobb. As Mudcat tells it, Cobb was soon seen trying to slip out of the stadium.

Vic Power didn’t look for racial tension as a ballplayer. As a Puerto Rican, he wasn’t even accustomed to it- unlike U.S. ballplayers who were black. Back in his homeland, people of various skin color mixed freely. But in the major leagues, he endured the indignities of 1950s America: racially segregated restaurants, hotels, cabs and drinking fountains.

Power’s style would not permit him to blend in with the scenery, either. Ted Williams and Stan Musial had their own distinctive flair; Willie Mays had the basket catch. Vic Power played with his own signature style- only in his case, he revolutionized the way the first base position would be played by future generations.

There was the one-handed catch. Power knew the ‘right’ way to catch was with two hands- he even taught the two-handed catch when he coached young players in retirement. But he had learned to catch with one hand as a youngster himself, and his throwing hand only got in the way. Even as a veteran, fans would hoot and holler when he’d make a one-handed catch. Then there was the sweeping motion he would use when catching throws at first. And when fielding a sacrifice bunt, he was highly successful in cutting down the lead runner at second or third base- even though many batters bunted away from him, to the third base side of the infield. He would also play the first base position well behind the bag, instructing the infielders to throw to the bag: Power would arrive in time to catch the throw.

Today, all first basemen catch throws with one hand, stretching to shorten the distance of the throw. They also field their position several feet behind first base, giving them more range to field ground balls. Mays’ basket catch was nice, but he didn’t alter the way the game was played.

Today, all first basemen catch throws with one hand, stretching to shorten the distance of the throw. They also field their position several feet behind first base, giving them more range to field ground balls. Mays’ basket catch was nice, but he didn’t alter the way the game was played.

Born Victor Felipe Pellot Pove, the ballplayer known in the U.S. as Vic Power originally was forbidden to play baseball as a child by his father. He did not intend to give up the game, and he eventually turned professional, playing for a minor league team in Quebec. The French-speaking fans there laughed at his name- ‘Pellot’ sounded very similar to a crude French slang word for a private female body part- so he changed his name. When his mother had attended grade school, a teacher had mistakenly recorded her name- Pove- as ‘Power’. He began to assume this as his professional surname. (He kept the name ‘Pellot’ when playing in the Winter leagues south of the border; some Puerto Ricans who did not understand the situation considered him a sell-out).

Power was an exceptional ballplayer while in Canada, and the New York Yankees signed him. By all objective measures, he’d earned a spot on the Yankees roster, and looked to be on track to join them along with New York’s other black prospect, Elston Howard. The Yankees, who still had not had a black player on the roster six years after the big league debut of Jackie Robinson, decided not to invite Power to Spring training. The rumors were that Power enjoyed dating women of all skin colors, and that he was a flashy dresser who did not back down from a fight. Upon hearing the news of the Yankees’ decision, many protesters rallied in front of Yankee stadium since it seemed obvious that the motivation was racially fueled. Power should have become a big leaguer in his early 20s, but was held back for a few years in a sign of the times.

The Philadelphia Athletics signed Power, and he had some success there (and in Kansas City, to where the franchise soon moved). Again, he was confronted with racism, especially in Florida in the Spring. Once, he differed with a store clerk over the proper refund on an empty pop bottle. Upon hitting the road with the team, the local police stopped him. They intended to haul him in, until Power’s teammates stepped up and vouched for him. One of the officers was said to have declared that if Power had been arrested, he would have been lynched.

Famously, Power once entered a Florida restaurant and was informed by a waitress that they did not serve “Negroes”. He replied that she was not to worry: he did not eat “Negroes”, and that he only wanted some rice and beans.

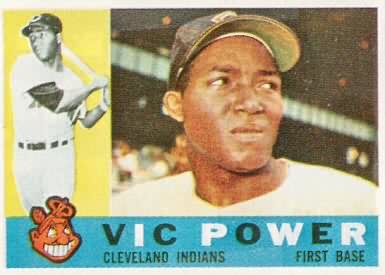

You know that New York Yankee great Roger Maris was once in the Cleveland Indians’ farm system. Do you know how he made his way to the Yankees? Suprisingly enough, Maris wasn’t one of the several star players the Tribe gifted to the Yankees. Cleveland traded him in 1958, to the Athletics- for Vic Power. The Kansas City A’s were the franchise who served Maris on a silver platter to New York (I saw a published lament that the A’s franchise gave all their good players to the Yankees. They apparently didn’t get the memo that only Cleveland can complain about such things!).

You know that New York Yankee great Roger Maris was once in the Cleveland Indians’ farm system. Do you know how he made his way to the Yankees? Suprisingly enough, Maris wasn’t one of the several star players the Tribe gifted to the Yankees. Cleveland traded him in 1958, to the Athletics- for Vic Power. The Kansas City A’s were the franchise who served Maris on a silver platter to New York (I saw a published lament that the A’s franchise gave all their good players to the Yankees. They apparently didn’t get the memo that only Cleveland can complain about such things!).

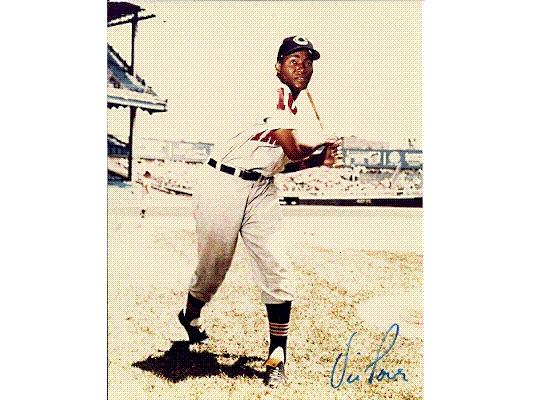

Wearing number 10 as a Cleveland Indian from 1958 through 1961, Vic Power made the All-Star team for the third and fourth times in his career. He won Gold Gloves at first base all four seasons- and would have won more except the award was only instituted for the first time in 1958. His batting average over that time ranged from .268 to .317. He had two hitting streaks of at least 20 games in 1958, and one in 1960. Power hardly ever struck out, although he was a free swinger who did not walk much.

And he maintained his style, his flair. Power was known to blow kisses to the fans in the stands. He liked fancy cars. He was a fan of both jazz and classical music. He joked with all of his teammates- Mudcat Grant has recalled the time Power missed a popup down the right field line and proceeded to cut his glove into small pieces because he didn’t need it any more. But Power competed with deadly seriousness.

A quintessential Vic Power moment came on August 14, 1958. He stole home in the eighth inning against a deliberate Detroit Tigers pitcher, who had a slow windup. Then in the tenth inning, Power was on third base again. The bases were loaded with the score tied. Rocky Colavito had homered twice in the game, and was at the plate with two out. On each of the first three pitches, Power faked a break for the plate. On the fourth pitch, he kept running and beat the tag by catcher Charley Lau for the Tribe win. Two steals of home to win the game- and Power ended up with only three steals on the season!

After his major league career, Power coached such major leaguers-to-be as Roberto Alomar, Jose Oquendo, Jerry Morales, Willie Montanez and Jose Cruz.

In 2000, Vic Power was named one of the 100 all-time Cleveland Indians. Pretty solid vindication of his worth to the 1950s teams. And for ‘my money’, worth the price of Roger Maris.

Thank you for reading. Next Week: Blast From The Past: The Frank Robinson/Gaylord Perry Clubhouse.

Right: Vic Power sliding into base vs. Nellie Fox of the White Sox.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)