Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Lingering Items--Homecoming Edition

Lingering Items--Homecoming Edition

Maybe I'm running counter to the flow again, but excuse me if I can't get too excited either way about Jim Thome returning to the Indians. I wasn't one of those who said that he should be booed when he left and I won't be one of those who believe we should embrace him with open arms now that he's gone through his tour of duty with the major leagues and can't find anywhere else to play.

Maybe I'm running counter to the flow again, but excuse me if I can't get too excited either way about Jim Thome returning to the Indians. I wasn't one of those who said that he should be booed when he left and I won't be one of those who believe we should embrace him with open arms now that he's gone through his tour of duty with the major leagues and can't find anywhere else to play.

Thome left the Cleveland Indians for the same reason every really good player eventually leaves the Cleveland Indians: money. That's not a sin. It wasn't Thome's fault, for example, that the Indians decided Thome wasn't worth the same level of riches that other clubs were willing to pay him. It's the reality of the business of baseball.

Indeed Thome maximizing the value of his skills by selling himself to the highest bidder is mostly the American way. All the b.s. about how Thome should have given the Indians a hometown discount was written mostly by 5-figure sportswriters pushing a quaint notion of a bygone era that they themselves wouldn't follow if the next newspaper down the block offered them a 10% raise.

But having left the Indians in exactly the same way that Albert Belle left the Indians, Thome should expect nothing more from the local fans then the same level indifference he showed them when he left. Maybe he was conflicted about taking all those millions, I don't know. But he certainly wasn't conflicted enough to leave some of them on the table and I don't begrudge him that. But neither should he nor Indians management begrudge that same level of indifference returned in kind by the very fans they're trying to placate.

If Thome's return is bothersome, it's not because of Thome personally but what he represents: all that is wrong with the way major league baseball is run in general and the way the Indians are run in particular.

I don't want to get into my 7,000th screed about baseball's lack of economic parity, but it is useful to remember that when Thome left, the Indians made him a very competitive, albeit inferior, offer. The Philadelphia Phillies, unconstrained as they were by any sense of economics, had the media market and all the ancillary revenue that spills over from that to dip into when they signed Thome.

Cleveland and many teams like it are just not similarly situated, which is a very odd circumstance in which all the teams in the league are supposed to be equal partners. Baseball has long since stopped caring about the plights of its lesser teams even as Commission Bud Selig claims to celebrate the fleeting successes of the Indians and Pittsburgh Pirates before the crunch time of the season really arrives. The only small market team in the playoff hunt at the moment is the Milwaukee Brewers.

The truth is that there is every chance that had the Indians signed Thome that contract would have been the same millstone around the neck of the team that is Travis Hafner's contract, the player ironically Thome is now being called on to replace. Baseball owners share revenues like Apple and Microsoft share software strategies. For teams like the Phillies, they can just throw more money at their mistakes and leave the lesser jealous and the fans jaded.

So it's not a surprise that when players like Thome, broken down, aging and with skills actually diminishing, reach the end of their careers and no other team really wants them they return "home" like a prodigal son. It becomes a nice feel good story for those who still believe in the romance of sports but the reality is that the "trade" that brought him here was just a mostly cynical ploy by the Indians management to deflect fan attention away from the sinking fortunes of another lost season.

**

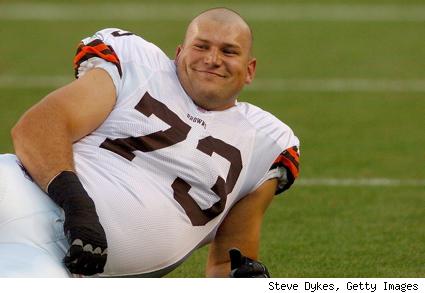

A better feel-good story is the Browns' signing of left tackle Joe Thomas to a 7 year contract for, I think, $100 billion, or something like that. The Browns signed Thomas just like other teams right now are locking up their versions of Thomas, because they can.

A better feel-good story is the Browns' signing of left tackle Joe Thomas to a 7 year contract for, I think, $100 billion, or something like that. The Browns signed Thomas just like other teams right now are locking up their versions of Thomas, because they can.

Whatever else you might think about the NFL's system, and it's been called all sorts of things by disgruntled players unhappy with their contracts, it works. The hard salary cap that exists in the NFL doesn't keep teams from making mistakes, but it does limit how long it has to live with those mistakes. It makes general managers appropriately aggressive as a result.

The key to Thomas' contract, similar to those being signed right now by other NFL stars, is that it's not completely guaranteed. The stated value of Thomas' contract is actually $84 million for 7 years but of that amount only a paltry $40+ million is guaranteed. By the time you figure in taxes and agent commissions, Thomas might only be left with about $20 million guaranteed.

NFL players went to the mattresses in an ill-advised strategy and came back with pretty much the same things they had when they left: a system in which owners are not required to guarantee player contracts. The firm money in Thomas' contract is in the form of signing, roster and other easily attained bonuses and the more speculative and hence less lucrative money are the salary figures each year. The contract is structured to be as cap friendly as possible. Its length spreads the guaranteed money over the life of the contract and hence makes it easier for the Browns to have sufficient salary room to sign other players.

In short, even if Thomas' career suddenly flames out in a year or two and he can't protect Colt McCoy's blindside any longer, the Browns won't be strapped for either cash or cap space. If the Browns lose him to injury, the collective bargaining agreement offers them even more relief.

In Thomas' case, unlike in many others, there's every chance he'll actually be with the Browns for the entire length of the contract. Offensive linemen of his caliber have about the longest shelf life in football. Even more encouraging is that there's little chance that Thomas will suddenly turn into Chris Johnson, the disgruntled Tennessee Titans' running back, and sit out if he learns a year or two into this contract that another left tackle is making more money.

Thomas is a stand up guy, a legitimate All Pro, and exactly the kind of player teams in any sport crave. His signing by the Browns not only represents a new high water mark for the franchise but underscores all that is right about the NFL and its economic structure.

**

If there's one thing that preseason football should counsel, it's perspective. The Browns sloppy play in a loss to the Philadelphia Eagles on Thursday night can be mostly attributed to the dog days of training camp crashing into a short week to prepare for a game that they really didn't prepare for anyway.

If there's one thing that preseason football should counsel, it's perspective. The Browns sloppy play in a loss to the Philadelphia Eagles on Thursday night can be mostly attributed to the dog days of training camp crashing into a short week to prepare for a game that they really didn't prepare for anyway.

Teams that really want to win preseason games can. But that is no marker whatsoever for how that same team will play once the regular season rolls around. Teams that use the preseason for its intended purpose, to refine technique and evaluate players, generally are better rewarded during the regular season.

The Browns look to be a team in the latter category. They surely could have played McCoy and the starters much later in the game when the Eagles' starters were off sitting in the locker room hot tub and watching the Kardashians or whatever it is that they do when they're bored, and come away with a victory. But what would have been the point to that? A meaningless victory at the expense of trying to figure out how to make one of the league's thinnest rosters a little more robust would have been time well wasted.

That doesn't mean of course that there aren't plenty of Browns' fans with long faces on Friday morning. Any time the Browns lose there are plenty of long faces, which explains the mostly permanent mopey expression of many during the fall and early winter months.

For perspective's sake, though, let's not lose the forest for the trees. Quarterback Colt McCoy didn't have a stellar performance statistically and was knocked around liberally. But he handled the adversity visited upon him by one of the league's best defenses (and certainly one of the league's best defensive backfields) well. Not every lesson is learned in victory. Most in fact are learned by after getting knocked down. So judge not the statistics but the bounce back come the regular season.

It wasn't as if there weren't bright spots. The Browns' defense, particularly the line and the linebackers, looks significantly better under new coordinator Dick Jauron. There were a few blown assignments and some of the rookies got schooled by some of the Eagles' veterans, but the difference in approach between last year's unit and this year's is almost as striking as the difference between an abacus and an iPad.

The offense is still a work in progress but as it struggled against the Eagles, perhaps some of it was best explained by Bernie Kosar while providing commentary for the game. He noted that the Eagles defense is used to practicing against virtually the same offense that the Browns run. There is nothing the Browns did, from the formations to the blocking schemes, that the Eagles haven't seen over and over in practice during training camp.

That doesn't mean that the offense isn't going to struggle against teams less prepared. It will, particularly early. What remains to be seen is whether it will struggle to score on the same level as the Indians struggle to score. I doubt it.

So keep the loss in perspective. Everyone is still standing. Besides, with one tedious preseason game remaining, perhaps the only thing we can all say with certainty is that the regular season can't arrive soon enough.

**

With Jim Thome's return to the Tribe, this week's question to ponder: Who would you rather have seen return to the Indians, Thome or Omar Vizquel?

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)