Indians Archive

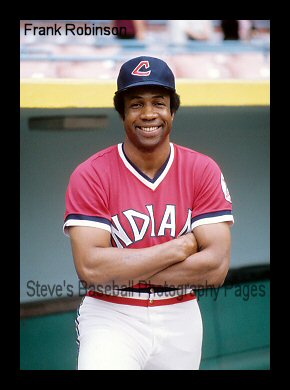

Indians Archive  Tribe Legends of the Spring: T.J. O'Hays Gets a Tryout with Mgr. Frank Robinson

Tribe Legends of the Spring: T.J. O'Hays Gets a Tryout with Mgr. Frank Robinson

Oh, so you’ve never heard of this guy either? Join the club. And until 1975, neither had new Cleveland Indians manager Frank Robinson.

Oh, so you’ve never heard of this guy either? Join the club. And until 1975, neither had new Cleveland Indians manager Frank Robinson.

Over the previous six winters, Robinson had managed the Santurce Crabbers of the Puerto Rican winter league.

The league consisted of six teams, and in earlier years had served to nudge major league baseball toward integration through its acceptance of black players from the U.S. The Santurce club was its unofficial flagship. The franchise’s second generation owner was  Hiram Cuevas. Sporting the nicest ballpark in the league (Hiram Bithorn Stadium, photo), the Crabbers were the only independently owned team: as Cuevas’ sole source of income, they needed to turn a profit. The Puerto Rican league had served as a training ground for several major league ballplayers and managers. This included Cuevas’ friend, legendary Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver. When Weaver moved on from Santurce as he transitioned to managing the Orioles, he recommended Oriole Frank Robinson as his replacement. The Crabbers’ 23-player roster was packed with quality players (including the maximum eight non-Puerto Ricans), and they won the league title. Unfortunately for the manager, unpredictability made the season quite a bit more difficult to navigate than it would have seemed. There were players who were deeply buried in major league managers’ dog houses.

Hiram Cuevas. Sporting the nicest ballpark in the league (Hiram Bithorn Stadium, photo), the Crabbers were the only independently owned team: as Cuevas’ sole source of income, they needed to turn a profit. The Puerto Rican league had served as a training ground for several major league ballplayers and managers. This included Cuevas’ friend, legendary Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver. When Weaver moved on from Santurce as he transitioned to managing the Orioles, he recommended Oriole Frank Robinson as his replacement. The Crabbers’ 23-player roster was packed with quality players (including the maximum eight non-Puerto Ricans), and they won the league title. Unfortunately for the manager, unpredictability made the season quite a bit more difficult to navigate than it would have seemed. There were players who were deeply buried in major league managers’ dog houses.  There were players who had had bizarre incidents while stateside (like eventual Cleveland Indian Leo Cardenas, who’d pulled an ice pick on Reds teammate Jim O’Toole). Of course, a favorite type of Latin American story for baseball reporters involves voodoo, and

There were players who had had bizarre incidents while stateside (like eventual Cleveland Indian Leo Cardenas, who’d pulled an ice pick on Reds teammate Jim O’Toole). Of course, a favorite type of Latin American story for baseball reporters involves voodoo, and Robinson indeed had a player who was obsessed with evil spirits. He was the second baseman- and one day, he was too mortified to approach second base. It seems there were two nearby sticks that were crossed, portending an ominous warning.

Robinson indeed had a player who was obsessed with evil spirits. He was the second baseman- and one day, he was too mortified to approach second base. It seems there were two nearby sticks that were crossed, portending an ominous warning.

In 1975, the 39-year-old Robinson was about to follow in Weaver’s footsteps, ascending to a major league managerial role. The Indians had signed him off waivers at the end of the 1974 season, from the California Angels. The follow-up move to sign Robinson make him the manager was hardly surprising, although it was momentous and historic. Following through on his commitment to Cuevas, Robinson managed Santurce one last season in 1975, after he had signed with Cleveland.

(Doesn't the Santurce photo of Robinson remind you of Cheech Marin from the same era?)

While in Puerto Rico for his final winter season, Frank Robinson received a long-distance telephone call. The caller introduced himself as T.J. O’Hays, and told the manager that he had a slide he wanted to show him. Other managers had warned Robinson about guys asking for tryouts, but he was intrigued. So all this guy could do was slide? The caller was supremely confident and enthusiastic. His slide was revolutionary. Even if the fielder is waiting to tag the runner, he would fail to do so. Robinson wanted to hear how this would work, but the caller wanted to show him, in person. He wanted to come to spring training. When Robinson told him he’d need to be invited by the Indians, he said he’d pay his own expenses. Fair enough- the manager told him that would be fine.

Fast forward to the last week of spring training, 1975. The previous few weeks had seen a national media crush in Tucson, covering the start of the first black manager’s first season. Robinson had navigated through psychological struggles with veteran pitchers. He’d established some managerial philosophies, such as how he would like to handle umpires and player curfews. And by this late date, the roster was basically set.

Then the telephone rang. It was T.J. O’Hays. Calling about his slide. He would arrive the next day. He had shown the slide to the Oakland A’s, but owner Charlie O’ Finley apparently wasn’t impressed. O’Hays dropped the name of A’s slugger Reggie Jackson to Robinson- at least in O’Hays’ world, Reggie was a personal reference.

While contacting a major league manager to demonstrate a cutting-edge slide may seem unorthodox, it made perfect sense to approach Charlie O. Finley first. Finley was the eccentric owner of the A’s in the 1970s who had advocated changes in major league baseball, such as using orange baseballs, using a mechanical ‘rabbit’ that popped out of the ground behind the home plate area to deliver balls to the umpire, and the designated hitter.

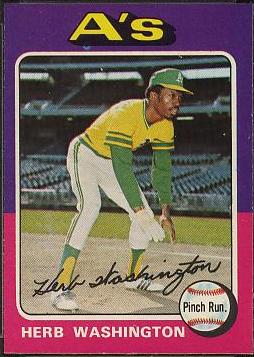

In 1974, Finley hired sprinter Herb Washington as the team’s ‘designated runner’. Washington had no prior pro baseball experience, but was used throughout the season as a pinch runner. He was a member of the 1974 World Series championship A’s. Famously, however, he was picked off by Mike Marshall of the Dodgers in the ninth inning of Game Two. Washington never batted, fielded, or pitched, yet played in 105 games as a pinch runner. His Topps baseball card lists his position as “Pinch Run.”.

In 1974, Finley hired sprinter Herb Washington as the team’s ‘designated runner’. Washington had no prior pro baseball experience, but was used throughout the season as a pinch runner. He was a member of the 1974 World Series championship A’s. Famously, however, he was picked off by Mike Marshall of the Dodgers in the ninth inning of Game Two. Washington never batted, fielded, or pitched, yet played in 105 games as a pinch runner. His Topps baseball card lists his position as “Pinch Run.”.

It doesn’t seem unreasonable that T.J. O’Hays looked to the A’s for a tryout. I wonder who else showed up at Finley’s doorstep in the mid-1970s.

The next day, the Indians were in Mesa, Arizona, where the A’s trained. A long-haired, thirty-something blond guy walked into the Indians clubhouse holding a small bag. As all eyes followed him, he walked over to Frank Robinson and introduced himself as T.J. O’Hays. “I called you about the slide.” Robinson looked at him and told him they didn’t have a uniform. Undaunted, O’Hays announced he would get one from the A’s. From Reggie Jackson.

After a short while, the manager was out on the field. O’Hays appeared, wearing Oakland A’s pants and a windbreaker. Robinson noted:

“He had on a pair of spikes that were patched up with protective metal on each side that made them look like football high-tops for a knight in armor. Then he taped a big sponge over his pants on each hip.”

He was ready.

Robinson walked him to the rightfield corner of the outfield, and tossed a base on top of the grass. O’Hays instructed him to stay at the base. Again, from Robinson:

“He trotted away, then turned and ran at me as if I were covering the bag. Suddenly he did a flip in the air with a Kung Fu kick and he landed on the base with one foot, whomp.”

He looked at Robinson, waiting for a reaction. No fielder would stand and tag such a runner. And if he tried, the runner could decide to slide instead. Robinson allowed that it was something he had not seen. O’Hays began offering to teach all the Indians players his move. Before Robinson could respond, O’Hays launched into his next proposal. He could pitch. All he needed to do was warm up with the two-pound rock he retrieved from his bag. He moved off on his own and began tossing the rock ten feet one way, then back. He would be happy to provide the Indians pitchers with this effective warm up drill. Of course, it could easily take two weeks to sufficiently teach the technique.

He looked at Robinson, waiting for a reaction. No fielder would stand and tag such a runner. And if he tried, the runner could decide to slide instead. Robinson allowed that it was something he had not seen. O’Hays began offering to teach all the Indians players his move. Before Robinson could respond, O’Hays launched into his next proposal. He could pitch. All he needed to do was warm up with the two-pound rock he retrieved from his bag. He moved off on his own and began tossing the rock ten feet one way, then back. He would be happy to provide the Indians pitchers with this effective warm up drill. Of course, it could easily take two weeks to sufficiently teach the technique.

When he was done with the rock, O’Hays was ready to begin pitching. Coach and former catcher Jeff Torborg was his batterymate. Unfortunately, after two or three pitches, O’Hays was holding his arm in pain. They sent him off to trainer Jimmy Warfield, and about fifteen minutes later, the prospect reappeared in street clothes. This had been his big break, and he might later lament his rotten luck- but wait. He hadn’t shown Robinson his catcher’s mitt. A dial on the mitt measured the speed of the pitch. All you had to do was calibrate it: you knew Nolan Ryan threw 100 miles per hour- so catch one from him, then see what the dial showed, and then figure other pitchers’ speed based on that. When the manager informed O’Hays that Ryan doesn’t always throw 100 miles per hour, O’Hays was surprised. But that fact did not matter: “But there must be something I can do with your ball club. I’ll do anything. I need the money.” For Robinson, what began as an amusement ended with a measure of admiration mixed with pity. If only some of his ballplayers had that kind of enthusiasm.

Frank Robinson’s Cleveland Indians started the season slowly. Veteran players failed to produce, and sowed dissension in the clubhouse. At the end of April, the Indians paid a visit to New York. The manager received a call at the hotel. It was T.J. O’Hays, who informed him that he was alive and well. And his arm was improving. He just needed a few more weeks.

The season continued to frustrate the new manager. The young kids had promise, but the veterans continued to fail to impress. They began to be dealt off, and the kids generated some excitement. The team’s struggles with the fundamentals of the game never did improve.

In early August, the Indians visited New York on another road trip. Frank Robinson met with the American League president to face disciplinary action. Back at the team hotel, a hand-delivered letter was waiting for him. It was from T.J. O’Hays. After three tries, his shoulder was finally able to handle his strenuous exercise routines. During the down time, he had concentrated on his legs. He wore ankle weights, although he did gain weight due to feeling depressed over not being able to throw. But the shoulder was healing up better than ever. And oh by the way, John Ellis had “broke his balls” over the new slide, and was the “rottenest bastard” he ever met. He would have taught Ellis a lesson, but didn’t want to cause a problem. He would go on to explain how he didn’t like to use force with people, but sometimes it’s the only thing people understand. Like his buddy who bullied people when he drank. And the prostitute he declined, who kicked him repeatedly. He hoped Robinson wouldn't let him down and “change his mind” about the slide. He wanted the manager to say hi to Jackson. And he had been thinking about another new way to slide, on plays where the pitcher takes the throw on a sprint to first: a body roll.

Come mid-September, the Indians returned to New York one final time. No sign of T.J. O’Hays. Frank Robinson figured his arm failed to come around.

The historic season was about over. Several story lines had played out, while some stretched into the offseason and beyond. Apparently, the saga of T.J. O’Hays had ended.

Resources for this article include the online CNNSI Vault, and Frank: The First Year by Frank Robinson, as told to Dave Anderson.

Thank you for reading.

More recent photo of Frank Robinson with Leo Cardenas.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)