Indians Archive

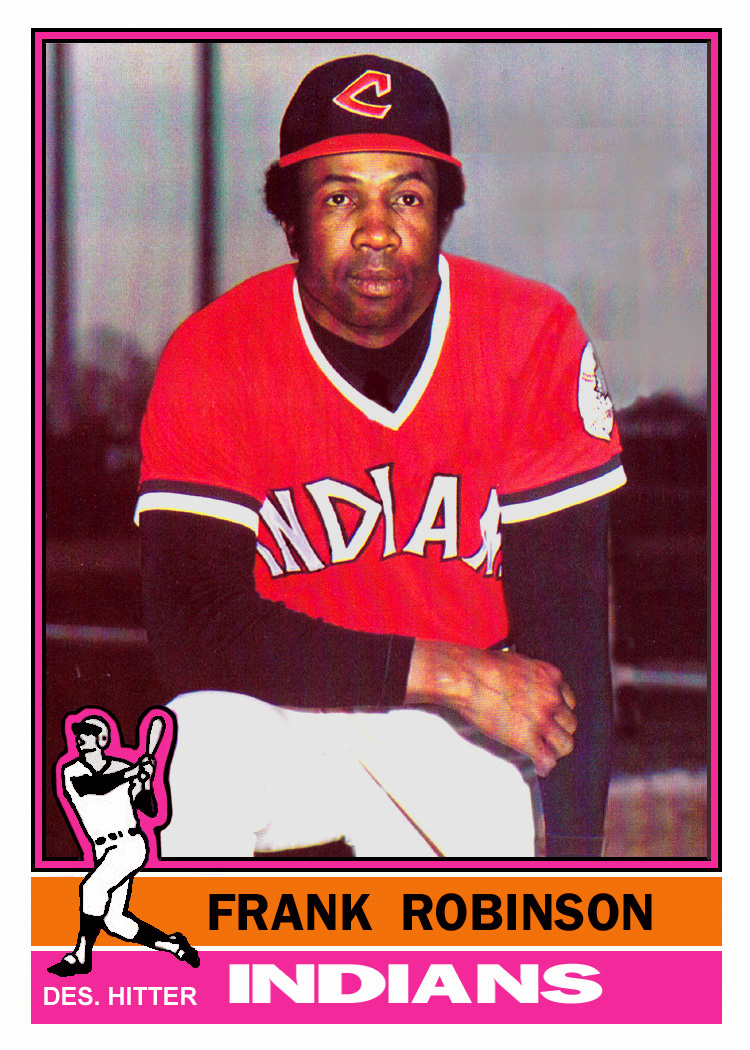

Indians Archive  Tribe Game Vault: 4/8/75. Frank Robinson Homers in Historic Opener

Tribe Game Vault: 4/8/75. Frank Robinson Homers in Historic Opener

The animated energy that was pouring out of the echoing stadium began to fill The Theatrical Restaurant. Although the old bar and eatery off East 9th Street had seen better days as a historic jazz venue, it was still in its prime as a place for a diverse drinking crowd to congregate. Local and national media mixed with prominent sports figures and other celebrities. Inside stories of notable Clevelanders of the past still resonated there. And although it was a place where the shady and the righteous mingled, proper decorum reigned.

The animated energy that was pouring out of the echoing stadium began to fill The Theatrical Restaurant. Although the old bar and eatery off East 9th Street had seen better days as a historic jazz venue, it was still in its prime as a place for a diverse drinking crowd to congregate. Local and national media mixed with prominent sports figures and other celebrities. Inside stories of notable Clevelanders of the past still resonated there. And although it was a place where the shady and the righteous mingled, proper decorum reigned.

The teens had been excused from school at the request of their uncle Jack; he’d accepted Opening Day tickets as appreciation for an undisclosed ‘favor’ he’d granted over the winter. His throwback fedora and topcoat may have appeared too formal for a modern ballgame, but his nephews couldn’t imagine him in any other attire. The postgame traffic was preventing the gameday crowd from leaving the area; without a second thought, Jack led the boys to the watering hole on Short Vincent. The waiter greeted Jack formally by name, and seated the foursome at ‘his’ table. From there, they could see most of the restaurant (at least, on days when the aisles weren’t crowded with standing patrons). Most noticeable was the stage, above the circular bar. Today, the stage was still, and dim. It would come to life later in the evening.

The teens had been excused from school at the request of their uncle Jack; he’d accepted Opening Day tickets as appreciation for an undisclosed ‘favor’ he’d granted over the winter. His throwback fedora and topcoat may have appeared too formal for a modern ballgame, but his nephews couldn’t imagine him in any other attire. The postgame traffic was preventing the gameday crowd from leaving the area; without a second thought, Jack led the boys to the watering hole on Short Vincent. The waiter greeted Jack formally by name, and seated the foursome at ‘his’ table. From there, they could see most of the restaurant (at least, on days when the aisles weren’t crowded with standing patrons). Most noticeable was the stage, above the circular bar. Today, the stage was still, and dim. It would come to life later in the evening.

The sounds of excitement had not waned from the fans who had witnessed the Tribe victory. Comments from the other tables were occasionally clearly heard over the din.

“That was a really nice ceremony before the game.”

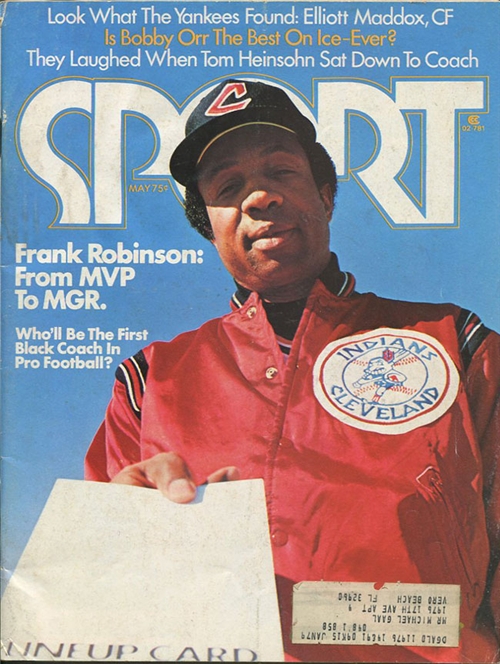

Indeed. Mrs. Jackie Robinson had thrown out the first pitch. Her comments to reporters before the game included heartfelt congratulations to the city of Cleveland for welcoming the first black big league manager. She wished her husband had been alive to see this day, and she hoped Frank Robinson was the first of many future black managers. Rachel Robinson defined ‘class’. Photo of Ms. Robinson is from 2008.

Indeed. Mrs. Jackie Robinson had thrown out the first pitch. Her comments to reporters before the game included heartfelt congratulations to the city of Cleveland for welcoming the first black big league manager. She wished her husband had been alive to see this day, and she hoped Frank Robinson was the first of many future black managers. Rachel Robinson defined ‘class’. Photo of Ms. Robinson is from 2008.

Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn said a bunch of things to the 58,000 in attendance that, to the kids, basically meant, “As the first black big league manager, Frank Robinson has made this an important day, one that promises a more hopeful future.” (Or, on the business end of the giant stadium’s public address system, “As-as-as-as the-the-the first-first-black-black-big league-league-manager-ger-ger-ger…”) The Indians were all lined up on the field, and Kuhn faced them and the left field stands. Media types- especially photographers- swarmed the space behind the players. The lakefront temperature was in the 30s; everyone had their hands in their pockets or tucked under folded arms. Puffs of steam bloomed from under baseball caps like white dandelion tops.

Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn said a bunch of things to the 58,000 in attendance that, to the kids, basically meant, “As the first black big league manager, Frank Robinson has made this an important day, one that promises a more hopeful future.” (Or, on the business end of the giant stadium’s public address system, “As-as-as-as the-the-the first-first-black-black-big league-league-manager-ger-ger-ger…”) The Indians were all lined up on the field, and Kuhn faced them and the left field stands. Media types- especially photographers- swarmed the space behind the players. The lakefront temperature was in the 30s; everyone had their hands in their pockets or tucked under folded arms. Puffs of steam bloomed from under baseball caps like white dandelion tops.

(Come to think of it, Bowie Kuhn dressed a lot like Uncle Jack. The teens chuckled about that for a moment, while Jack was greeting acquaintances who’d arrived. When he turned back to face the boys, their smiles remained as they sipped their root beer. With his brow slightly furrowed in curious amusement, Jack nursed his highball as he eyed his nephews.)

“They said on the radio that this morning, Seghi told Robinson to hit a home run.”

This was also relayed by another friend of Jack’s. His cigar had announced his approach before he reached their table. He greeted the nephews in the respectful manner one might address one’s boss’ children (although what it was Jack did for a living was an elusive subject for the boys). Phil Seghi was the Indians’ general manager, and had hired Robinson as field manager. Apparently, after the two men had spoken that morning, Seghi asked Robinson, “Why don’t you hit a home run today?” Robinson’s reply was to the effect of, “You have got to be kidding.” Seghi laughed about that later, saying he never dared dream Robinson really would do it. But he knew not to doubt him as a player.

In their seats prior to the game, Jack had talked to the boys about Frank Robinson, the ballplayer. “What we’re watching here today is one of the greatest players in the history of baseball. He has MVP awards from each league. He won the Triple Crown in 1967. That’s tops in the league in batting, homers and RBIs. He was MVP of a World Series. He is fourth all-time on the home run list. Do you know who is ahead of him?”

In their seats prior to the game, Jack had talked to the boys about Frank Robinson, the ballplayer. “What we’re watching here today is one of the greatest players in the history of baseball. He has MVP awards from each league. He won the Triple Crown in 1967. That’s tops in the league in batting, homers and RBIs. He was MVP of a World Series. He is fourth all-time on the home run list. Do you know who is ahead of him?”

Sure, the kids knew that. If it weren’t for the respect they had for their Uncle Jack, they wouldn’t have bothered to answer. “Aaron, Ruth and Mays.”

Jack nodded. “Aaron, and even Mays, have kind of overshadowed Robinson a little bit. But just look at the guy’s accomplishments- and he is still amazing, even now.”

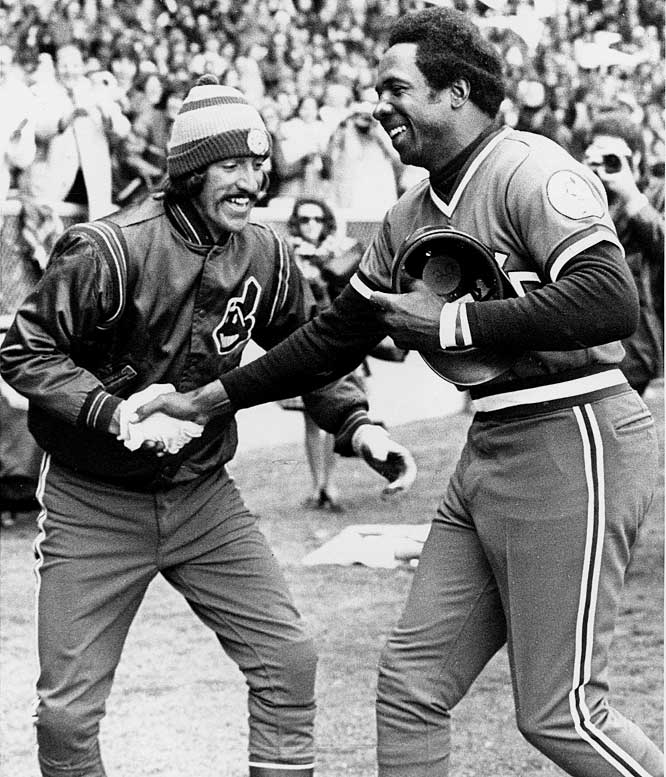

The scene had been perfect. The sun was just beginning to warm the ballpark at the start of the Indians’ half of the first inning. Oscar Gamble had led off with a foul fly ball to third baseman Graig Nettles. The crushing noise from the crowd increased almost before the first out was recorded. Frank Robinson was up. He sauntered to home plate in his traditional way, with his bat dragging at his side. Later, he admitted he wasn’t mentally ready to face “Doc” Medich at the start of the at-bat. Medich got the call on the first pitch, a low curve ball. Robinson glared at the umpire momentarily. The second pitch was a strike on the outside corner- a good pitch. Medich then dropped down and threw a sidearm curve that Robinson fouled off. Suddenly, the hitter snapped to attention: with that sidearm motion, Medich was trying to show him up. The pitcher wasted a curveball outside, then a fastball inside. Robinson was ready when the next pitch arrived. He said later that Medich’s motion was over the top, and rather than arching his hand, the ball came straight out – either a slider or a fastball. Robinson guessed fastball, and crushed it to left. His world settled to complete silence, as it always did when he hit a ball deep. He wasn’t sure if left fielder Lou Piniella would have a play on the ball or not- Piniella leaped, but did not come down with the baseball. Robinson trotted around the bases in quiet solitude… until he passed second base. Third base coach Dave Garcia was grinning and jumping up and down. The crashing explosion of the cheering stadium suddenly broke through Robinson’s consciousness. He crossed home plate and George Hendrick was there to greet him. Robinson, hat-head and all, doffed his helmet to his wife and kids up in the private loge. Goosebumps.

“So much for Gaylord and Robinson not getting along.”

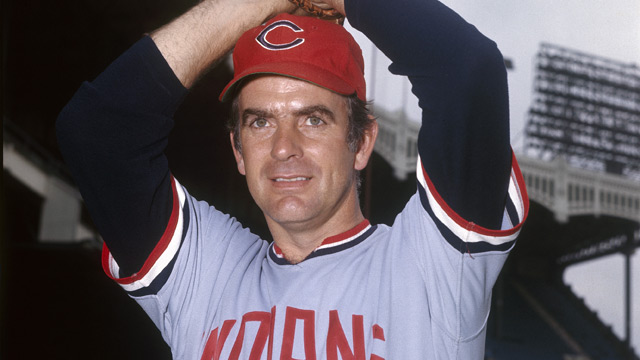

Yep. Sure, Perry and the player-coach had feuded when the hitter joined the team late in 1974. Perry had averaged over 20 wins per season in Cleveland since 1972, when he won the A.L. Cy Young Award while pitching for the last-place team. The Indians signed Robinson, and Perry wanted to be paid “a dollar more.” They held a shouting match in the clubhouse (actually, Robinson later admitted he did all the shouting).

Yep. Sure, Perry and the player-coach had feuded when the hitter joined the team late in 1974. Perry had averaged over 20 wins per season in Cleveland since 1972, when he won the A.L. Cy Young Award while pitching for the last-place team. The Indians signed Robinson, and Perry wanted to be paid “a dollar more.” They held a shouting match in the clubhouse (actually, Robinson later admitted he did all the shouting).

Over the previous several weeks, Perry had repeatedly flouted the authority of the new manager. He didn’t see the point in running foul pole to foul pole. He liked to take infield practice. He bristled at running backwards in drills. Robinson differed with Perry on each of these points. Perry would never confront the manager face to face; he would mumble to other players, or to reporters. He would take passive-aggressive shots at Robinson, and flirt with other teams who might want to trade for him.

However, on Opening Day, when the Indians’ ace had finished his pregame warmup throws, it was showtime. After pouring his first pitch over the plate, there was Gaylord Perry- lobbing a three-bouncer to the dugout, with a wave to Frank Robinson. Here was a keepsake: the first ball used in his first game as manager.

Then after Robinson hit the historic home run in the first inning, there was Perry again- leading the charge out of the home dugout and hugging Robinson. Not to mention after the game was won, when the manager came out and had his arm around his pitcher.

Yep, Jack agreed. They were going to get along just fine.

(Eeeeeeyeahhhh, maybe…)

“Ladies and gentlemen, may I introduce you to your first place Cleveland Indians.”

Oh, yes. This was a huge theme. The New York Yankees were a thorn that had lodged directly in their collective side. Through the 1950s, the Tribe had averaged about 95 wins per season, yet only won the pennant in 1948 and 1954. The Yankees won it every year besides those two.

More recently, the Indians had been in the process of shipping their promising farm system to other teams, often with the return of cash as an important consideration. The home team was nearly broke.

Playing for the Yankees in the opener in 1975 included:

Lou Piniella. Actually, the Indians owned his rights on two separate occasions. They originally signed him in 1962; the Washington Senators then drafted him from the Tribe. After being traded to Baltimore, the Indians reacquired him. Along came an expansion draft: the Seattle Pilots selected Piniella. They would trade him to Kansas City. He’d wind up with the Yankees and win a bunch of pennants.

Graig Nettles. A fantastic defensive third baseman who could hit. Nettles had come up through the Indians’ farm system and showed signs of stardom. He was moved to New York, ostensibly because outfielder Buddy Bell was ready to be inserted at third. Apparently, there was no room on the team for both players.

Chris Chambliss. First baseman. Cleveland’s 1971 American League Rookie of the Year. Dealt in a typically horrible trade.

(Also on that Yankee team were Bobby Bonds, the first 30HR/30SB major leaguer and who would join the Tribe in a few years, and Thurman Munson, the Yankee catcher from Canton. Munson actually made it very clear that his preference was to join the Indians- and thereby play his home games near his home.)

Jack's nephews were too young to offer more than a figurative shrug. But to Jack, beating the Yankees had provided a special satisfaction.

To Jack and the boys, sharing the momentous day with likeminded revelers at The Theatrical enhanced the experience of Opening Day. Eventually, the traffic began to move, and it was time for the boys to get home. Jack settled up with the waiter, who gave an extra grin as he looked Jack in the eye and thanked him again.

Jack wasn’t one to let his bar tab ride, although it wouldn’t have mattered on this day.

He’d return later. Naturally.

Thank you for reading.

Sources include Frank Robinson:The Making of a Manager by Russell Schneider and Frank: The First Year by Frank Robinson and Dave Anderson. Also, the online SI Vault as well as the Baseball Digest, which is searchable in Google Books back to 1945.

Below: John Lowenstein greeting Frank Robinson after the historic home run.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)