Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Tribe Game Vault: 7/31/32. All-Time Tribesman Mel Harder Opens the Stadium

Tribe Game Vault: 7/31/32. All-Time Tribesman Mel Harder Opens the Stadium

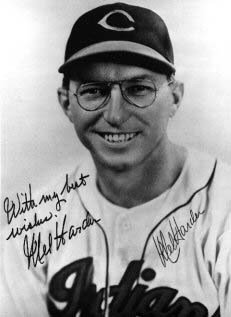

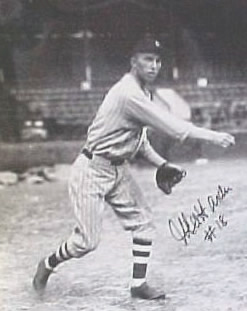

The 22-year-old righty was on the bump, tossing his pre-game warm-ups to catcher Luke Sewell. Speaking of which, the Cleveland Indians ballclub was doing some bumping along of its own that 1932 season. It was the end of July and the Tribe was a distant third in the American League standings. This day, however, was bursting with anticipation.

The 22-year-old righty was on the bump, tossing his pre-game warm-ups to catcher Luke Sewell. Speaking of which, the Cleveland Indians ballclub was doing some bumping along of its own that 1932 season. It was the end of July and the Tribe was a distant third in the American League standings. This day, however, was bursting with anticipation.

League Park, the cozy, long-time home of the Indians on the near east side, was beginning to outlive its functional usefulness. Sitting on an intersection of streetcar lines had been an advantage in years past. With the dawning of the age of the automobile, however, the land-locked ballyard’s lack of parking was fast becoming a liability. The 27,000-capacity limited attendance at key times, as well.

The new stadium on the lakefront was dedicated and open for business in July of 1931. Most observers assumed the Indians would automatically leave League Park and move into their new home. They may not have realized that a new era had arrived in other, more subtle ways as well. The stadium would represent the first park that a major league team did not own. Indians president Alva Bradley engaged in protracted negotiations with the city for over a year. The ceremonial signing of the lease by Bradley and Cleveland mayor Ray T. Miller was held at home plate prior to the inaugural Indians game on July 31, 1932.

The game was on a Sunday, against the defending World Series champion Philadelphia Athletics. It was a team dotted with several future hall-of-fame players. One of these was the A’s starting pitcher, Lefty Grove. The young Indians starter was Mel Harder.

The game was on a Sunday, against the defending World Series champion Philadelphia Athletics. It was a team dotted with several future hall-of-fame players. One of these was the A’s starting pitcher, Lefty Grove. The young Indians starter was Mel Harder.

Harder would later reflect on pitching that day as the “biggest thrill of my career.” The pomp and circumstance, the 80,000+ crowd, and the historical significance of the day made its impression on everyone. Former Indians stars such as Nap Lajoie, Tris Speaker and Cy Young were in attendance, as were various dignitaries.

But Harder was not supposed to pitch that day- his normal turn in the starting rotation was to be the following day. Wes Ferrell, the scheduled Indians starter, turned up with a sore arm. He mentioned as much to Roger Peckinpaugh, the Tribe’s friendly, popular manager. Peckinpaugh’s move was automatic: he told Harder to take the ball.

Back on the mound: Harder had been told to groove a strike to the first hitter. It would be part of the planned festivities- the hitter would take a strike, the crowd would erupt again, and the ball would be tossed out of play. It would be presented to Ohio governor George White, who was seated in a field box.

Problem was, the leadoff hitter for the A’s either didn’t know the plan, or wasn’t playing along. Second baseman Max “Camera Eye” Bishop put a tremendous swing on the ball and sent it rocketing to left. It reached the seats out of play, but Harder’s eye’s widened. It was time to buckle down and play some ball. Bishop did reach on the stadium’s first base hit, earning the historical footnote. Harder struck out center fielder Mule Haas, walked catcher Mickey Cochrane, and struck out left fielder Al Simmons before inducing a fly out off the bat of first baseman Jimmy Foxx. Decades later, Harder’s pitching would have been described as “Ubaldo-ing” his way through the inning.

Problem was, the leadoff hitter for the A’s either didn’t know the plan, or wasn’t playing along. Second baseman Max “Camera Eye” Bishop put a tremendous swing on the ball and sent it rocketing to left. It reached the seats out of play, but Harder’s eye’s widened. It was time to buckle down and play some ball. Bishop did reach on the stadium’s first base hit, earning the historical footnote. Harder struck out center fielder Mule Haas, walked catcher Mickey Cochrane, and struck out left fielder Al Simmons before inducing a fly out off the bat of first baseman Jimmy Foxx. Decades later, Harder’s pitching would have been described as “Ubaldo-ing” his way through the inning.

Harder settled in and actually pitched a great game, allowing only four more hits in his eight innings of work. Famously, he struck out three future hall-of-famers in a row at one point: Cochrane, Simmons and Foxx. Lefty Grove was up to the task as well. He allowed four hits in his complete-game effort.

The Indians threatened to score twice in the game against Grove. The first time was in the third inning. Second baseman Bill Cissell singled, was bunted to second, then advanced to third on a groundout but was stranded there. In the seventh inning, Tribe star Earl Averill singled. Another favorite, left fielder Joe Vosmik, bunted and beat the throw to first. Up came first baseman Eddie Morgan, who… yes. Yes, Morgan bunted. Grove hopped off the mound, grabbed the ball and winged it to third base for the force out on Averill. It was reported that Grove made a great play on the ball, and his being lefthanded was said to have helped in that instance. With one out, Grove struck out Sewell. Cissell stepped to the plate and crushed a line drive to right. The full house was said to have stood as one and cheered- momentarily. The ball hit in foul territory. Having dodged that bullet, Grove retired Cissell and the Indians on a ground ball to the second baseman Bishop.

In the top of the eighth inning, the A’s answered the Tribe’s seventh inning threat. First, Bishop drew a leadoff walk. Haas bunted him over to second. Cochrane singled him home. Harder later described the pitch Cochrane hit as a fastball inside. The bouncer up the middle just did elude the pitcher as well as Cissell.

In the bottom of the ninth inning, with two out, the Tribe’s Morgan sent a long fly ball to right field. Bing Miller of the A’s caught the ball at the wall.

Remember, the outfield wall in the early days of Cleveland Stadium was the outfield stands. There was no ‘temporary’ fence installed until 1947. The acreage in that outfield was enormous: 320 feet from home plate to each foul pole, and 450 feet to dead center field. Morgan’s fly ball would easily have been a home run in League Park, with its short right field wall. (The stadium’s designers wanted the outfield to be large, to make home run hitters ‘earn it’. They considered the home run as a cheap gimmick.) Also of note, fans were allowed to sit in the bleachers in center field. Batters would note that the white shirts in the background made it hard to pick up the ball out of the pitcher’s hand. Soon, outfield seating would be restricted to left and right field only.

Remember, the outfield wall in the early days of Cleveland Stadium was the outfield stands. There was no ‘temporary’ fence installed until 1947. The acreage in that outfield was enormous: 320 feet from home plate to each foul pole, and 450 feet to dead center field. Morgan’s fly ball would easily have been a home run in League Park, with its short right field wall. (The stadium’s designers wanted the outfield to be large, to make home run hitters ‘earn it’. They considered the home run as a cheap gimmick.) Also of note, fans were allowed to sit in the bleachers in center field. Batters would note that the white shirts in the background made it hard to pick up the ball out of the pitcher’s hand. Soon, outfield seating would be restricted to left and right field only.

Pitchers loved the stadium’s field dimensions. Hitters hated them. Babe Ruth would grumble that the huge outfield would hinder the Indians’ hitters- that an outfielder “ought to have a horse” with him in the outfield.

The Indians would play 31 games at the stadium in 1932. They won 19 of them. The team finished fourth in the league that year, and was considered to be an underachieving ballclub.

The stadium struggled with political corruption and graft- one of the dangers of a taxpayer owned facility. Controversies - such as accusations of favoritism in contractors used, to bloated staff during the dormant winter months, to the appointment of stadium presidents who had no qualifications or experience for such a position – popped up from time to time. The field itself had a terrible drainage problem, requiring the replacement of the turf three times by the end of 1933. Besides ruining the field, water quickly flooded the dugouts during a hard rain. Years later, it was discovered that field drains were installed incorrectly, and that many drain tiles were crushed when the field was rolled and laid out.

There was a lot of good about the stadium, as well. Those include the memories of Mel Harder.

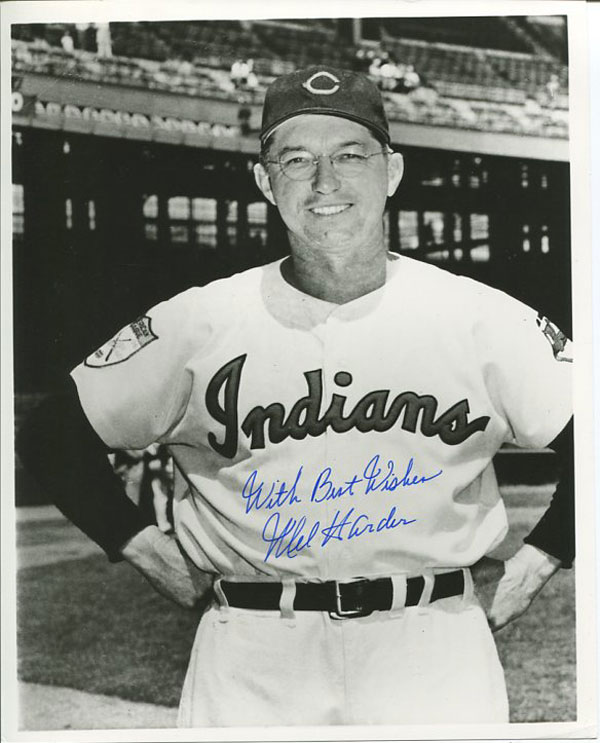

Harder would earn himself a spot on the proverbial short list of all-time Cleveland Indians of the 20th Century, behind Bob Feller.

We’ll look at more of Harder’s career sometime down the road.

Thank you for reading.

****** Hey, Sports Time Ohio- nice photo of Harder in your link to this article. The background gives a sense of the left field stands of old League Park, with the wrap-around bleachers section in the corner. By the looks of Harder, he appears a little older than he would have been when they began playing games at the stadium in 1932. So the Indians would likely have been in that period where they were splitting home games between the two parks.

Sources for this article include Cleveland Stadium, Sixty Years of Memories (James A. Toman); Game Face, Indians Scorecard Magazine (1993), and my constant companion, an item that would be a great gift to any Tribe fan: The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (Russell Schneider).

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)