Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Tribe Game Vault: 6/7/38. The Great Johnny Allen Torn Shirt Controversy

Tribe Game Vault: 6/7/38. The Great Johnny Allen Torn Shirt Controversy

(Sitting with my cell phone at my chin, as a microphone prop. Conjuring up my best Bob Costas voice.) Decades later, notable events from baseball’s past become footnotes in the annals of sports. Many are still found in the sports page, under the heading of “On This Date.” Through most of the 20th Century, the National Pastime was king, and its rich history lives on through documentation on a level that far surpasses any other sport. There are hundreds of fascinating stories lying just below the surface of today’s public consciousness, and that is one reason the old game will thrive for many generations yet to come.

(Sitting with my cell phone at my chin, as a microphone prop. Conjuring up my best Bob Costas voice.) Decades later, notable events from baseball’s past become footnotes in the annals of sports. Many are still found in the sports page, under the heading of “On This Date.” Through most of the 20th Century, the National Pastime was king, and its rich history lives on through documentation on a level that far surpasses any other sport. There are hundreds of fascinating stories lying just below the surface of today’s public consciousness, and that is one reason the old game will thrive for many generations yet to come.

***

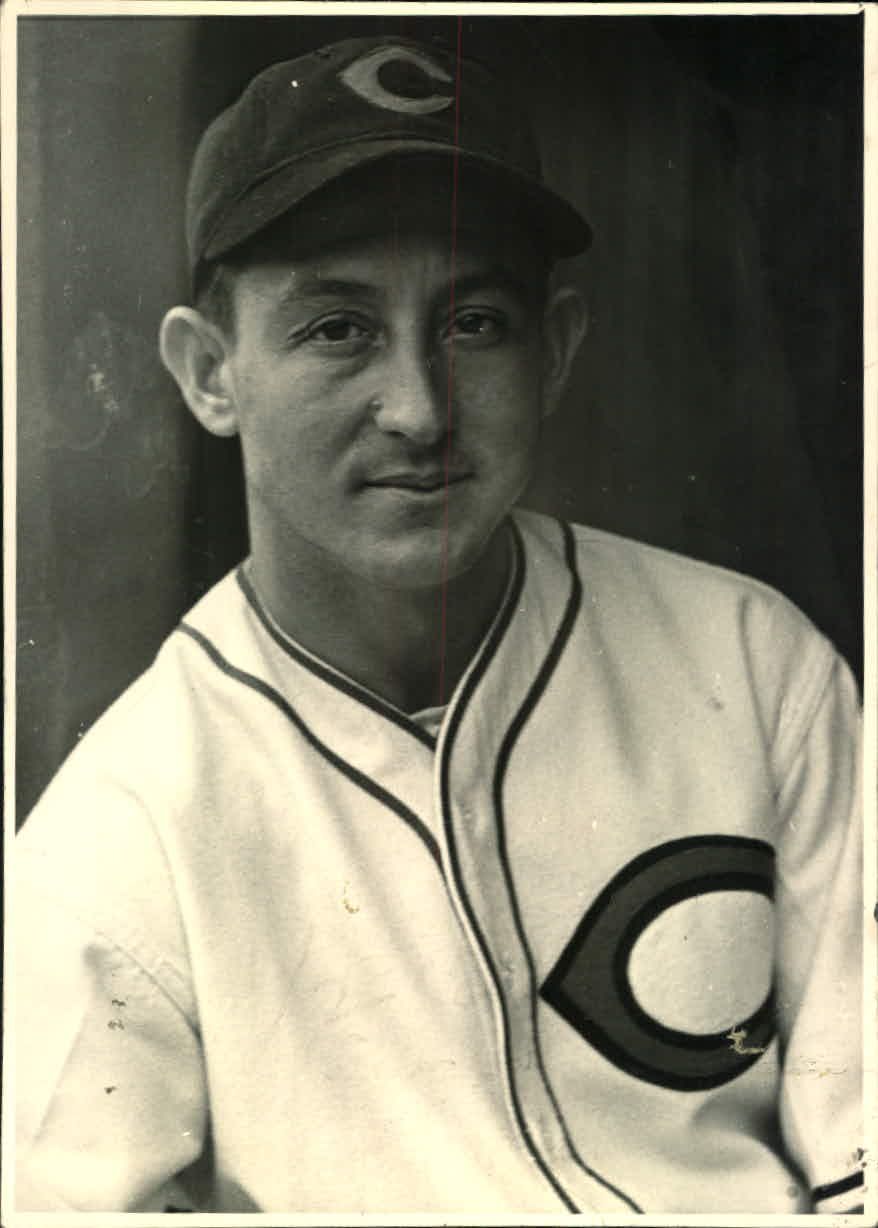

To be honest, I’d never heard of him. But we’ve all known guys like him. Indians pitcher Johnny Allen was like an old roommate of mine. He often was friendly, but very competitive. He had a notoriously short fuse that made others uncomfortable (my roommate’s motto was “I’d rather be pissed off than pissed on.”)

To be honest, I’d never heard of him. But we’ve all known guys like him. Indians pitcher Johnny Allen was like an old roommate of mine. He often was friendly, but very competitive. He had a notoriously short fuse that made others uncomfortable (my roommate’s motto was “I’d rather be pissed off than pissed on.”)

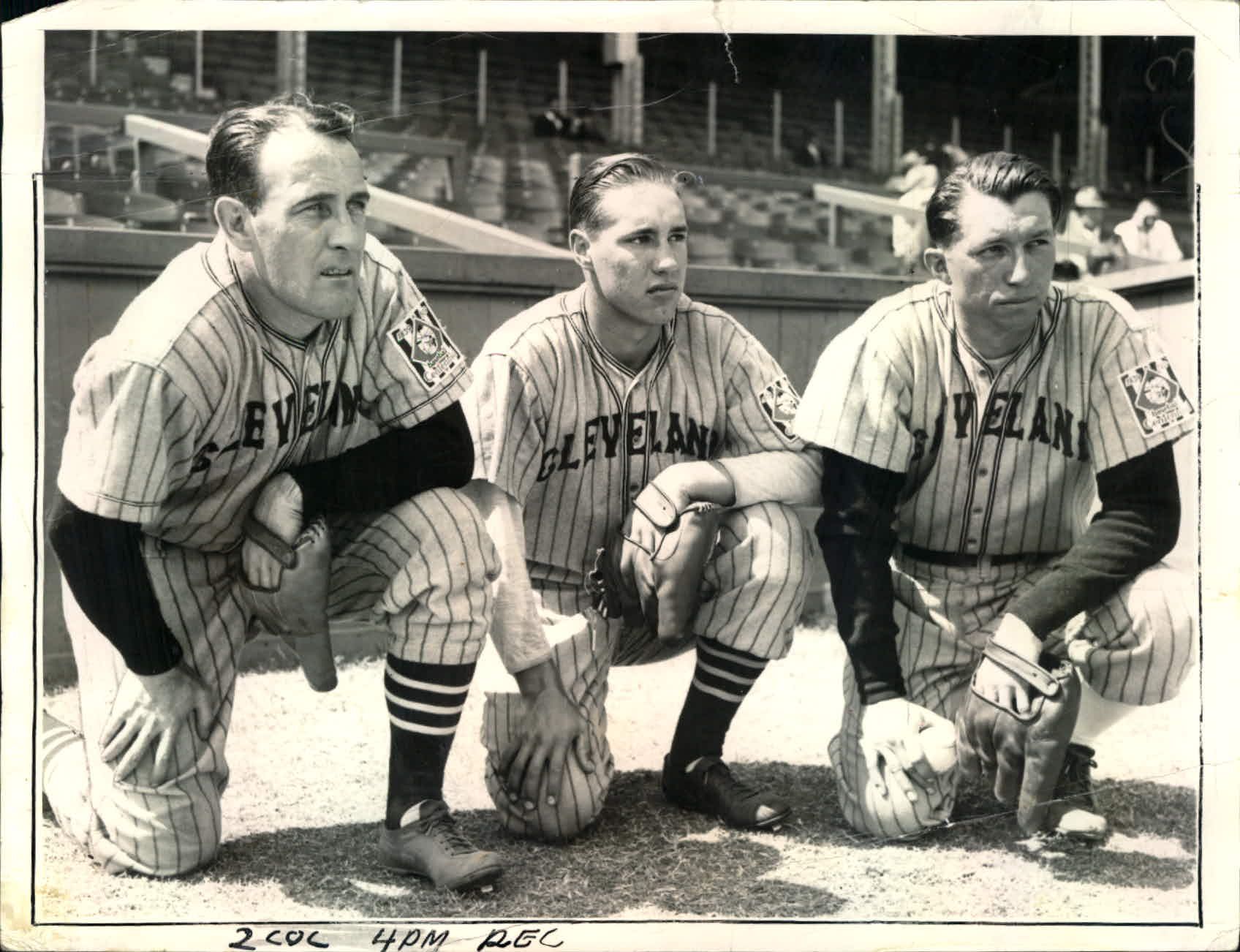

Even though he brought it on himself, it is too bad Johnny Allen was known mostly for his anger. He was a dominant starting pitcher with several teams, including the late 1930s Cleveland Indians alongside veteran standout Mel Harder and young phenom Bob Feller. He had come to the Tribe in a 1936 trade with the New York Yankees. Into his third season with the Tribe, he had already tallied 35 wins against 11 losses. In 1937, he’d reeled off 15 straight, losing in his final start to the St. Louis Browns by a 1-0 score. The streak was interrupted for three weeks by an emergency appendectomy, but resumed without any lingering effects.

So by 1938, Allen was perhaps the finest pitcher in the game. Better than Carl Hubbell, Dizzy Dean, and Lefty Grove. Over his previous six seasons, he’d led the major leagues in winning percentage (.739), strikeouts per game (5.65), and had allowed only four hits or less in 18 games.

Through the years, he was harassed by accusations that he threw a spitball. Opponents would coax the home plate umpire to inspect the baseball for signs of the now-illegal pitch. There was no basis for the suspicion; the charade was meant to get inside Allen’s head and knock him off his game.

And it worked. He seethed when he had to surrender the ball to the ump- in some cases, several times in one inning. At least once, he needed to be restrained from throwing punches at the opposing third base coach, who’d stopped a game for a ball inspection. The pattern of accusation finally ended when Cy Slapnicka of the Tribe’s front office appealed to the American League offices. League president Will Harridge declared that a thorough investigation revealed no grounds for the spitball charge, and Allen resumed pitching without such harassment.

Of course, there were plenty of other reasons for John Rocker, er, I mean Johnny Allen to lose his cool. He was even known to curse the clock from the dugout, when he was ready to take the mound before it was time for his warm ups. Tantrums after games could feature knocking bar stools down, kicking over sand-filled ashtray urns, and discharging public fire extinguishers- sometimes on unsuspecting bystanders.

Allen had an explosive fastball, which he did not hesitate to throw at the head of hitters. It didn’t matter to Allen if it were the regular season or an exhibition game. Not only was this in the pre-helmet era, but it was also before umpires were bestowed with the authority to toss pitchers out of the game when it was suspected they were purposely hitting batters. The bean ball was not uncommon in those days, but Johnny Allen was considered the meanest pitcher in the game. In the National League, in the latter part of his career, he was said to have ruined the career of good-hitting Cincinnati Red Frank McCormick by knocking him down so often. During one game, the Reds manager/third base coach began hollering at Allen after he’d knocked McCormick down three straight times. Allen challenged the manager to a fight, and the two converged at the mound- along with the entire Reds team. Allen announced that he would take them on, one at a time. He invited the first combatant to come forward. Nobody did. The next time McCormick came to the plate, Allen drilled him in the ribs!

Umpires felt the wrath of Allen; he was known to need to be restrained after being called for a balk.

Fellow teammates? You didn’t want to be the reason Johnny Allen lost, as Odell Hale (photo) was in that 1-0 game that ended Allen’s 1937 winning streak. Hale’s error led to the lone run of that game. Allen had to be restrained twice from attacking the forlorn third baseman- once in the clubhouse and again on the train ride home to Cleveland. As you may have guessed, his quick temper is the reason the Indians were able to pry him away from the Yankees. Late in 1935, Allen had lost a game due to a misplay by a young outfielder. He publicly exploded on his manager for playing the rookie, ensuring he'd be dealt.

Fellow teammates? You didn’t want to be the reason Johnny Allen lost, as Odell Hale (photo) was in that 1-0 game that ended Allen’s 1937 winning streak. Hale’s error led to the lone run of that game. Allen had to be restrained twice from attacking the forlorn third baseman- once in the clubhouse and again on the train ride home to Cleveland. As you may have guessed, his quick temper is the reason the Indians were able to pry him away from the Yankees. Late in 1935, Allen had lost a game due to a misplay by a young outfielder. He publicly exploded on his manager for playing the rookie, ensuring he'd be dealt.

Allen had a fastball that broke in the strike zone. His heater was considered to be in the top three in baseball (Feller's was #1), but he had several other effective pitches, like his overhand curve and a change. But his second best pitch was his slider, and some credit him for inventing the pitch. If he did not, he at least was perhaps the first pitcher to throw it so well. The slider became a favorite of Feller’s, and a specialty of Harder’s when he began his career as Tribe pitching coach. Under Harder’s tutelage, converted outfielder and future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon’s repertoire included a great slider. (Some actually consider Allen’s slider to be an early cut fastball.)

Allen was also known to vary the way he threw, so as not to tip off hitters to what the pitch would be. His delivery was liable to be overhand or straight side-arm.

Occasionally, hitters would ‘call’ his pitches. They were only pretending, but it was something else that got inside Allen’s head and rendered him less effective.

On June 7, 1938, however, Johnny Allen was on top of his game. His record stood at 7-1, with a 2.90 ERA. He was on the hill for the Tribe at Boston’s Fenway Park as the first place Indians were going for their 29th win against 14 defeats (those late 1930s teams were very good).

The Indians and Red Sox each scored a pair in the first inning, with Cleveland adding a third run in the top of the 2nd. When Allen returned to the mound, the Boston hitters began complaining that a rip in his right undershirt sleeve was a distraction. There was no rule against that (yet), but the sleeve flapped every time Allen threw. Apparently, he had worn the same shirt with the same rip over several starts that season. League president Harridge had stated that he did not approve of pitchers playing with such a shirt (other pitchers had also done so in the past).

The home plate umpire, Bill McGowan, had already thrown Allen out of a game in 1938- on Opening Day. He was said to have advised other umps: “Control the players, or they’ll control you.” McGowan told the pitcher to remove the shirt, or cut off the sleeve. As expected, Allen refused. Tribe manager Oscar Vitt approached the mound and told his pitcher to do as McGowan told him- and Allen proceeded to stomp off the field. After a few uneasy moments, Vitt called on Bill Zuber to pitch in relief of Allen- it was either that, or forfeit the game. Allen had put his team in a bind, as Zuber allowed three runs in the 3rd inning. The Indians pecked away and tied the game in the 4th, and scored two in the top of the 9th to win, 7-5.

One of the hitting heroes was Odell Hale. He went 2 for 4, with 3 RBI and a run scored.

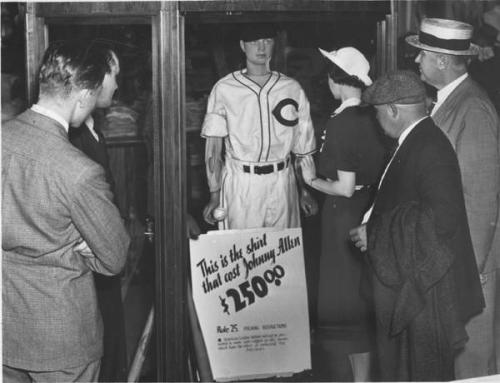

Vitt fined his star pitcher $250. Johnny Allen’s solemn vow was that he would never don the uniform of the Cleveland Indians, ever again. That is when Indians owner Alva Bradley swung a deal with the Higbee’s department store, on Public Square in downtown Cleveland. Higbee’s purchased the shirt- for $250- which Bradley paid to Allen. The store dressed a mannequin in the shirt and publicly displayed it in the main window. Vitt wasn’t happy, but the crisis was averted. The shirt is now displayed at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Vitt fined his star pitcher $250. Johnny Allen’s solemn vow was that he would never don the uniform of the Cleveland Indians, ever again. That is when Indians owner Alva Bradley swung a deal with the Higbee’s department store, on Public Square in downtown Cleveland. Higbee’s purchased the shirt- for $250- which Bradley paid to Allen. The store dressed a mannequin in the shirt and publicly displayed it in the main window. Vitt wasn’t happy, but the crisis was averted. The shirt is now displayed at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

That was right at about the apex of the career of Johnny Allen. In the All Star game at Crosley Field in Cincinnati that July, Allen blew out his arm while pitching  to Joe Medwick. A 12-1 start to the season gave way to a 2-7 finish. He underwent surgery, and was never as good afterward. He pitched for Cleveland through 1940, and bounced around the big leagues for four more seasons.

to Joe Medwick. A 12-1 start to the season gave way to a 2-7 finish. He underwent surgery, and was never as good afterward. He pitched for Cleveland through 1940, and bounced around the big leagues for four more seasons.

In an ironic twist, the brawling Johnny Allen would play -for him- a different role during the 1940 Indians’ season. This was the year of the infamous Cleveland Crybabies. The talented Indians had bristled under the abrasive Vitt (photo), who commonly stabbed the players in the back by ridiculing them in conversations with reporters. Many of the players banded together and approached owner Bradley, asking for the firing of their manager. Bradley declined (until after the season was over)- and the team was subject to merciless taunting when traveling on the road. Johnny Allen- along with Mel Harder- had strongly suggested the team allow the two of them to privately appeal to Bradley, thereby avoiding the public backlash. So here was Johnny Allen, pseudo-peacekeeper.

(Back to Costas) There’s no doubt that Johnny Allen and his team suffered from his volatile temper. How? Whatever Allen may have possessed in in classic pitching traits, he lacked other qualities in spades, and in his case those qualities: the short fuse, the lack of a filter on the venom he produced, and a discomfort he fostered in others that can’t be explained, but could certainly be felt - the whole Allen persona - derived from how he saw the world and his place in it. Those qualities, no matter how one is saddled with them, are a liability. Perhaps especially in sports. Too bad for Allen, and those like him. To be sure, however, it made him and the Indians one of the most fascinating stories of the games we follow.

Thank you for reading. Sources include The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia by Russell Schneider, Baseball Digest, a John Steadman article in The Baltimore News-American, The St. Petersburg Times, and baseball-reference.com.

Also, apologies to Bob Costas, whose Sunday Night Football in America Halftime Monologue on Tim Tebow was pretty much lifted and given the opposite treatment at the end of this article.

Below: Allen, Feller, and Harder.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)