Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Tribe Game Vault: 7/14/46. Lou Boudreau's Innovative Approach vs. Ted Williams

Tribe Game Vault: 7/14/46. Lou Boudreau's Innovative Approach vs. Ted Williams

Curiosity, imagination, intelligence and perseverance converge in forging a quintessential American trait: the spirit of innovation. The western free market has fostered the invention of countless technological and medical advances, from the telephone, the airplane, and the polio vaccine to the Band-Aid and duct tape. And Spam.

Curiosity, imagination, intelligence and perseverance converge in forging a quintessential American trait: the spirit of innovation. The western free market has fostered the invention of countless technological and medical advances, from the telephone, the airplane, and the polio vaccine to the Band-Aid and duct tape. And Spam.

Then there are the new ideas or methods that change our lives, or the course of human history. Landing men on the moon. The factory assembly line. Nuclear power. (I’ll leave the debate over the benefits of that to the Cleveland Fan’s No Holds Barred forum- but it seems clear to this writer that nuclear power is still in its infancy as an energy source for the future.)

With the creation of new ideas helping to define the United States’ ascendancy in the last century, why wouldn’t it have permeated the sports landscape, as well? And as the king of American sports over that period, Baseball has seen its share of innovation.

With the creation of new ideas helping to define the United States’ ascendancy in the last century, why wouldn’t it have permeated the sports landscape, as well? And as the king of American sports over that period, Baseball has seen its share of innovation.

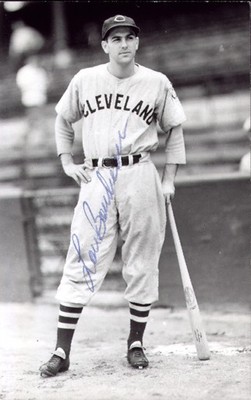

As Kris Kristofferson wrote in a song Janis Joplin made famous, freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose. That was the tenor of Cleveland Indians manager Lou Boudreau’s locker room at Boston’s Fenway Park in Sunday, July 14, 1946.

In the first game of the double header, the powerhouse Red Sox defeated the struggling Indians, 11-10. The Tribe had jumped on Red Sox starter Joe Dobson for 4 earned runs in the first inning, knocking him out of the game. Immediately working on Boston’s bullpen appeared to bode well for Cleveland’s chances, for both games. Unfortunately for the Tribe, the Red Sox knocked starter Steve Gromek out in the 3rd inning as they tied the game at 5. The rest of the game seesawed between the two teams, with each team scoring three in one inning, and single runs in three other innings. The Red Sox found themselves down by two in the 8th, and erased that deficit with a three-spot against Indians reliever Joe Berry. Former Tribesman Jim Bagby, Jr. and Tex Hughson held the Tribe bats down just enough for the Red Sox victory.

Boston’s left fielder was cleanup hitter Ted Williams, the finest hitter of his era and perhaps of all time. Williams, to this day the major leagues’ last .400 hitter with  a .406 average in 1941, was hitting .352 at the time. He was unstoppable in that first game on July 14.. He’d gone 4 for 5, with 4 runs scored and 8 (eight!) RBI. His hits included a single and 3 home runs. As a co-worker of mine used to say back in the day: Cryminilli!

a .406 average in 1941, was hitting .352 at the time. He was unstoppable in that first game on July 14.. He’d gone 4 for 5, with 4 runs scored and 8 (eight!) RBI. His hits included a single and 3 home runs. As a co-worker of mine used to say back in the day: Cryminilli!

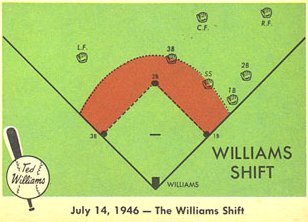

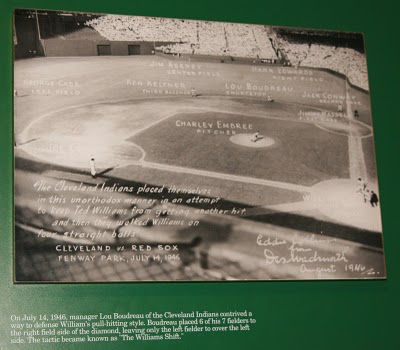

A left-handed hitter, almost all of Williams’ hits were to the right side of second base. Boudreau approached a chalkboard during the down time in between games, and devised a plan to counter the pull-hitting tendency of Williams. He diagrammed 1B Jimmy Wasdell playing deep and near the foul line, with 2B Jack Conway behind him and to his right. To Conway’s right and back near the right field fence would be RF Hank Edwards.

SS and manager Lou Boudreau would move over near the traditional second baseman’s spot, and 3B Ken Keltner would be positioned just to the right of the second base bag. CF Pat Seerey would play in shallow right-center. The only defender on the left side of second base would be LF George Case, playing a shallow left. Boudreau was ready to roll out this positioning during a future Williams at-bat.

This was not the first time such a shift was used in a major league game. Teams employed a similar, although slightly different, defensive shift against Cy Williams in the 1920s. Williams, who had played for the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies, was a left handed dead-pull power hitter during baseball’s  emergence from the ‘dead ball era’. Variations of the shift had been occasionally used to match up against pull hitters in subsequent seasons, as well.

emergence from the ‘dead ball era’. Variations of the shift had been occasionally used to match up against pull hitters in subsequent seasons, as well.

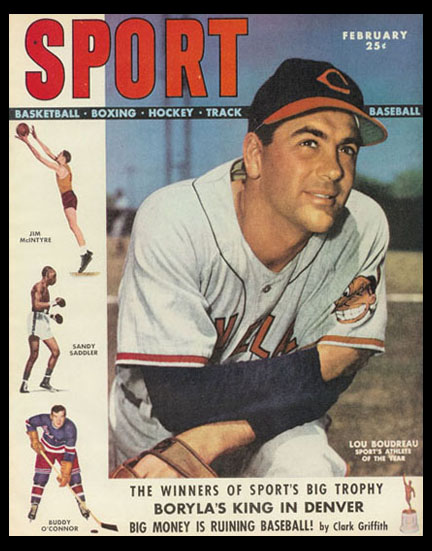

But when Lou Boudreau positioned his Cleveland Indians in the shift (briefly referred to as the ‘Cleveland Shift’- or the ‘C formation’, but now commonly known as the ‘Williams Shift’), it caught the imagination of the country. It was for the great Ted Williams, and it was in Boston. And the Indians and their ‘boy manager’ had some cache, as well.

In the second game of the twinbill on July 14, Ted Williams doubled in his first at-bat off Tribe starter Red Embree - down the right field line. Boudreau decided enough was enough. In the 3rd inning, the Red Sox were up, 3-1. Williams strode to the plate and watched the shift settle to the right side of the diamond. It was reported he stepped back from the batter’s box and had a hearty laugh. Everyone in attendance wondered if Williams would slap a ball to the left side, or even lay down a bunt towards third. Boudreau correctly felt he would instead accept the challenge of driving the ball through the shift (Boudreau later said that he considered the shift to be more of a psychological move rather than a tactical one).

Once the shift was in place, Williams swung at the first pitch. He hit a ground ball, right at Boudreau for the out.

Williams’ next at bat came in the 6th inning. Embree walked him on four pitches, with the shift on. Boston scored twice in that inning to go up 5-1.

In the 7th, Williams came up again. With Dom DiMaggio (Joe’s brother) on first, Boudreau modified the shift. He slid 3B Keltner over to the left side of the second base bag; Boudreau shifted closer to the base, and Conway was moved to his right, away from the line a bit more. Embree responded by walking Williams again. (Walking Williams might have been more effective than any shift,anyway.) The Red Sox scored again in the inning. They would win, 6-4, to complete the double header sweep.

Several teams began employing such a shift against Ted Williams. For some time, he refused to try to take the ball to the left side. Old baseball sages began  offering him advice on how to respond to the shift. Paul Waner, a long time star with the Pittsburgh Pirates, urged Williams to move his stance away from home plate. Ty Cobb (Detroit Tiger) famously sent Williams a two-page letter describing how he would attack the defense. Basically, Cobb had become frustrated that Williams would not hit the ball the opposite way. Keep in mind that through all this, Williams was as productive as usual at the plate.

offering him advice on how to respond to the shift. Paul Waner, a long time star with the Pittsburgh Pirates, urged Williams to move his stance away from home plate. Ty Cobb (Detroit Tiger) famously sent Williams a two-page letter describing how he would attack the defense. Basically, Cobb had become frustrated that Williams would not hit the ball the opposite way. Keep in mind that through all this, Williams was as productive as usual at the plate.

Later in the 1946 season – on September 13, the Indians began a home series against the Boston Red Sox at League Park. An announced attendance of 3,295 (ouch) was on hand for the Friday afternoon game. Boston’s Tex Hughson was to face Cleveland’s Red Embree. This was the same Cleveland pitcher that had started game two on July 14, when Lou Boudreau first unveiled the shift. Williams came up in the first inning, with the bases empty. Boudreau exaggerated the shift even more, bringing LF Pat Seerey in to essentially play a deep shortstop position. The entire left field expanse- much more spacious than League Park’s small right field area- was left completely unmanned. Williams hit a routine fly ball to left field. It dropped harmlessly, and rolled to the outfield wall- about 400 feet from home plate. Williams sped around the bases for the only inside-the-park home run of his career. The game would end as a 1-0 win for Boston, who clinched the pennant that day.

(Williams would later insist that he never intentionally attacked the soft spot of the shift; he only hit the ball where it was pitched. I'm not sure I buy that.)

Sorry, Tribe fans- no happy ending today. It’s just a great story highlighting American effort and achievement. And innovation, involving a rarely used defensive alignment that has become common when facing left handed pull hitters, even today.

Thank you for reading. Sources included www.baseball-reference.com, www.baseballlibrary.com, www.baseball-fever.com.

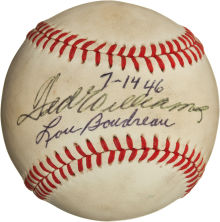

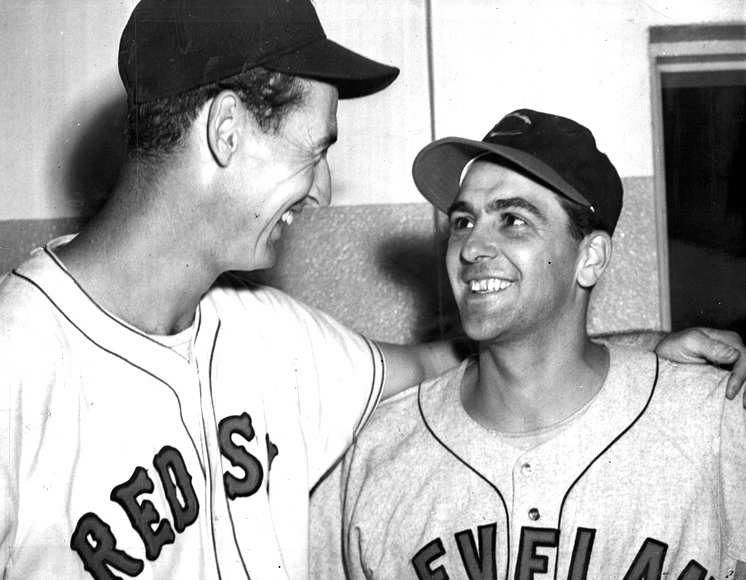

Photo below is from after the game in which the shift was first unveiled. Photographers back then liked to pose the principals of any momentous occasion together- and they seemed willing to do it, even when one had gotten the better of the other.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)