Buckeye Archive

Buckeye Archive  Why We Hate The Games We Love

Why We Hate The Games We Love

March Madness approaches...for many of us it’s the sporting event of the year at any level of competition. As of last year, every game is on live TV. No more “wrap-around” coverage, cutting to the most exciting game at any given time during the first two rounds. As long as you’re quick on the remote and the DVR....between CBS, TNT, TBS and the channel nobody knew existed a year ago...truTV, you can watch every bit of it...in all its mad glory.

March Madness approaches...for many of us it’s the sporting event of the year at any level of competition. As of last year, every game is on live TV. No more “wrap-around” coverage, cutting to the most exciting game at any given time during the first two rounds. As long as you’re quick on the remote and the DVR....between CBS, TNT, TBS and the channel nobody knew existed a year ago...truTV, you can watch every bit of it...in all its mad glory.

I figure we're numbed by the outrageous dollar figures thrown around in the modern sports world, and the fact that the combined TV networks paid the NCAA $771 million to telecast the 2011 NCAA Tournament hasn’t registered yet. An event that takes three weekends to play every winter is worth three quarters of a billion dollars to put on television...one time. The 14-year deal struck last year between the NCAA and the networks totals $10.8 billion. (That’s almost as much as will be wagered nationwide on the tournament in any given year)

But what do we care? When Ford tries to sell us an F-150, we’re switching to the game over on TNT. Besides, the schools love it. The athletic directors are all on board. Coaches especially are all in. John Calipari’s new contract at Kentucky calls for him to get a $700,000 bonus if he wins it all in any of his deal’s final three years. Many major college coaches have similar six-figure incentives to Dance Big.

But what if one of the teams in this year’s Final Four just flat out refused to play? What if a group of college kids got together and decided to protest the fact that, with the better part of a billion dollars being passed around to stage some 67 basketball games, the players actually putting on this heart-stopping display of talent and competition will receive exactly two things? Jack and Squat.  As unlikely as that boycott scenario sounds, it was actually something that the big shots at NCAA headquarters were concerned about some years ago when rumors surfaced that one particular team was contemplating that very thing should they reach the NCAA Finals. In his scathing indictment of the NCAA, “The Shame of College Sports”, The Atlantic’s Taylor Branch recounts the story as told by William Friday, former president of the University of North Carolina, and a co-founder of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics.

As unlikely as that boycott scenario sounds, it was actually something that the big shots at NCAA headquarters were concerned about some years ago when rumors surfaced that one particular team was contemplating that very thing should they reach the NCAA Finals. In his scathing indictment of the NCAA, “The Shame of College Sports”, The Atlantic’s Taylor Branch recounts the story as told by William Friday, former president of the University of North Carolina, and a co-founder of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics.

The school in question got knocked out before the finals, and the potential crisis, however unlikely, was averted. But as Branch writes of the astounding sum taken in for the tournament in 2011:

That’s three-quarters of a billion dollars built on the backs of amateurs—on unpaid labor. The whole edifice depends on the players’ willingness to perform what is effectively volunteer work.

[...] ...it was unnerving to contemplate what hung on the consent of a few young volunteers: several hundred million dollars in television revenue, countless livelihoods, the NCAA budget, and subsidies for sports at more than 1,000 schools.

Branch makes clear that the lifeblood of today’s NCAA is the cash from March Madness. College football conferences are negotiating their own deals with TV networks...or better yet, like Texas and the Big Ten, starting their own. The BCS is a separate organization that rings its own cash register. The other reality Branch brings home is the tenuous legal status of the NCAA’s definition of the “student-athlete”, which is soon coming under threat in court, even as it continues to barely pass the laugh test. More on that in a moment.

College Football and The BCS - A Love-Hate Thing

How can a sport this popular be so disgusting at the same time? Even if 15 of the games on the bloated 34-game bowl schedule are virtually unwatchable, we’ll still arrive in front of the tube with the cheese dip and the adult beverages to affirm our addiction to the whole enterprise. Still, college football and the way the NCAA administers and polices it provide some of the best examples of the disconnect between the ideals and the realities of intercollegiate athletics. I could keep you here all day with examples, but here are a few...

- The University of Georgia trades on the talent and on-field accomplishments of their star wide receiver A.J. Green (now a Cincinnati Bengal) by selling replicas of his game jersey in the campus store for up to $150 a pop. Green sells one of his own jerseys to help pay for a spring break trip, and the NCAA suspends him for four games of his senior season. Excuse me, son...we’ll be the ones making the money off that jersey, thank you very much. Rules are rules.

- The University of Georgia trades on the talent and on-field accomplishments of their star wide receiver A.J. Green (now a Cincinnati Bengal) by selling replicas of his game jersey in the campus store for up to $150 a pop. Green sells one of his own jerseys to help pay for a spring break trip, and the NCAA suspends him for four games of his senior season. Excuse me, son...we’ll be the ones making the money off that jersey, thank you very much. Rules are rules.

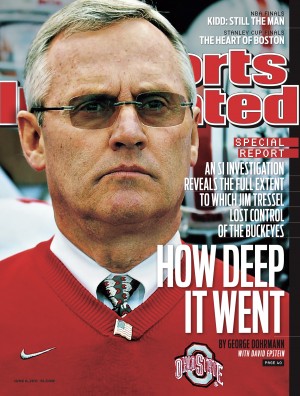

- Five Ohio State players earn five game suspensions for trading apparel and memorabilia for tattoos or a couple hundred dollars in cash. Justice for them would have to be swift and sure, the NCAA decided. Well...not that swift. Sugar Bowl CEO Paul Hoolahan (annual salary $645,386) was concerned about the need to “preserve the integrity” (which is to say, the TV ratings and ticket sales) of his annual New Year’s bash in the Big Easy, and lobbied to have the star Buckeye players’ punishments postponed till the following season.

Big Ten commish Jim Delany concurred, and used his influence with NCAA officials to let Terrelle Pryor and his mates participate. The one man to raise a peep of protest about the arrangement, OSU coach Jim Tressel, was outnumbered. Tressel then became the one unfairly pilloried for the decision by the national media herd.

- Many less significant and hence more silly violations are punished both on and off the field. One example close to home was OSU players getting penalized during a game for displaying an “O” to the TV camera by putting their two gloves together in a configuration designed by the apparel manufacturer to do exactly that, under an outfitting agreement with the university that pays OSU millions per year. Everybody’s happy except the player, (and in this case, the coach)

So it is the trivial and the ridiculous that are often punished, but even the more egregious offenses, like Cecil Newton’s solicitation of a six-figure bribe, are brushed aside with a suspension lasting less than 24 hours if they have the potential to interfere with, say, the “integrity” of the SEC Championship Game or the BCS title tilt.

Twisted Messaging

If there is a message of any kind to be delivered on the playing field as part of the player’s uniform or equipment, the NCAA and its member schools have seen to it that it's a dollar-driven one. The NCAA police have now ruled that a Tim Tebow may not reference a Bible verse, nor can a Terrelle Pryor support a maligned NFL quarterback with messages in their eye-black.

The average salary of the BCS bowl game CEO’s is over $500,000 annually. These are organizations by the way, that are set up as non-profits, and as such pay no taxes and are in some cases subsidized by taxpayers. To be fair, nearly all of these games do serve some charitable and/or community causes, and the Rose Bowl in particular does not pay its officers as handsomely as do the others.

Still it is the striking contrast between the two groups...the people staging the games, and the kids playing them...that galls the average fan. On one side you have the John Junkers of the world, throwing themselves “non-profit” $33,000 birthday parties and entertaining sponsors, school officials and various hangers-on with multi-million dollar outings like the Fiesta Frolic. On the other side you have the guys risking limb, if not life, on the football field...the so-called student-athlete that the ticket buyer and the TV-watcher are paying their money to see...who is not permitted to trade his own jersey for some pizza money. Small wonder that the average fan is experiencing the cognitive dissonance that comes with hating so much about the game he loves.

What This Isn’t About

Maybe another day we’ll rehash the debate about paying or not paying college athletes a stipend of some sort. I have always been one of those people who maintains that we do pay them significantly now...with an essentially free college education, the value of which can run into six figures these days. That’s six figures that non-athlete students often have to pay off over decades of loan payments. And the notion that we should set up a whole new regime of college athletic departments distributing cash to athletes for spending money?? Now...what could possibly go wrong there? Besides...what were you expecting here....solutions?

The Bubble

No, the focus here is more the ever-widening divide between college athletics and the educational mission of our university system. We’re all about “bubbles” these days. The dot.com bubble and the housing bubble are just the most recent examples. Now we’re hearing more and more about the higher education bubble, what with skyrocketing costs for degrees that in many cases offer no guarantee of related employment, and are saddling our young people with unmanageable debt burdens in a lousy job market. (I suspect that online education will soon become the needle that pricks that bubble, but again, that’s another column) The point is (you knew there had to be a point...somewhere...) that the cutbacks, layoffs and austerity measures taking place at universities nationwide seem somehow completely detached from the current state of major college athletics, with its $5 million per year coaches, its multi-billion dollar TV contracts, (complete with deep-pocketed sponsors and loyal TV audiences) and its eight-figure apparel deals with shoe companies.

The point is (you knew there had to be a point...somewhere...) that the cutbacks, layoffs and austerity measures taking place at universities nationwide seem somehow completely detached from the current state of major college athletics, with its $5 million per year coaches, its multi-billion dollar TV contracts, (complete with deep-pocketed sponsors and loyal TV audiences) and its eight-figure apparel deals with shoe companies.

But they’re not detached. The vast majority of the athletic departments at the 120 FBS schools are not able to pay for themselves, even with these newer outside revenues supplementing traditional sources like game ticket sales. An NCAA report demonstrates that in the 2009-10 year, all but 22 of them operated in the red, with the average shortfall in the neighborhood of $10 million annually. The previous year just 14 of 120 schools kept their heads above water. In most cases that deficit has to be picked up out of university funds...from general revenues and fees charged to non-athlete students, while scholarship athletes ride free.

To put it mildly, this is not going down well with faculty and staff who are being asked to pinch pennies in the chemistry lab while the football coach takes a private jet to woo a 17-year old tailback five states away. I’ll try to demonstrate below with some facts and some numbers what all of us can sense in one way or another, even as we love us our March Madness and our fall football season...

The system is broken.

OSU is the Exception to the Rule

We’ll stipulate at the outset that athletics can add to the prestige and the aura of a school, and to a degree, can enhance the college experience of (some, but not all) students. It can help attract students to a school even if they do not participate in intercollegiate sports. These benefits are in most cases intangibles though, and are difficult to measure at all, let alone translate to dollar figures.

Rich Exner at the Plain Dealer has done some solid reporting on the finances of athletics at Ohio’s universities, and while his figures are based on data from the 2009-10 school year, little has changed since in terms of the percentages. Ohio State, with its $123 million athletic budget is one of the few schools nationwide to support itself without subsidies from the university or the government. Their Ohio neighbor schools though, are regularly tapping into general funds and student fees to support their revenue-poor programs.

Ohio University is among the most heavily subsidized schools in the nation, with $18.7 million of their $22.7 million athletic budget coming either from student fees ($16.4 mil) or other state or government funding ($2.3 mil). And there is pushback from other quarters within the university, as reported at Inside Higher Ed.  This nationwide problem is at its worst right close to home here in the Midwest. In fact, according to Inside Higher Ed, 10 of the top 21 most heavily subsidized schools are members of the MAC athletic conference. Even with athletic budgets 20% the size of the behemoth in Columbus, these schools need to get between 49% (Toledo) and 82% (Ohio U.) of their revenues from non-athletic department sources. Kent State (80%), Akron (70%), and Bowling Green (65%) are among the most subsidized departments in the country.

This nationwide problem is at its worst right close to home here in the Midwest. In fact, according to Inside Higher Ed, 10 of the top 21 most heavily subsidized schools are members of the MAC athletic conference. Even with athletic budgets 20% the size of the behemoth in Columbus, these schools need to get between 49% (Toledo) and 82% (Ohio U.) of their revenues from non-athletic department sources. Kent State (80%), Akron (70%), and Bowling Green (65%) are among the most subsidized departments in the country.

Not everyone has a 105,000-seat stadium like Ohio State’s, and not everyone has the rabid following that allows them to charge extra premiums for the privilege of buying season tickets like the Buckeyes can. But the University of Akron is sitting there with a beautiful new facility, and they still can’t draw flies.

Among BCS conference schools, Rutgers, at a 42% subsidy level, is among the least self-sustaining athletic programs, and its non-athletic faculty and staff want to know why athletic spending continues to rise anyway. A Bloomberg study revealed that the top 120 athletic programs in the country are averaging a 26% subsidy level. You’d think that sooner or later those unmeasurable and intangible benefits to the university are going to run right up against some cold economic reality. It’s starting to happen at Rutgers and Ohio U., and I’m sure at other schools too.

Those Shoes

A decade or so ago, just about every NCAA basketball coach had a shoe contract of some sort with Nike, Adidas or Reebok. In most cases, the companies negotiated these deals directly with the coaches, leaving their university employers with no control over either the dollars or the sneakers.  As YahooSports’ Dan Wetzel detailed in a 2004 article, over the next few years two things happened to change the status quo. First, the proliferation of the one-and-done college player and the direct-high school-to-NBA player like LeBron James made the companies take a whole new look at the return on investment they were getting on the cash they were handing to college coaches.

As YahooSports’ Dan Wetzel detailed in a 2004 article, over the next few years two things happened to change the status quo. First, the proliferation of the one-and-done college player and the direct-high school-to-NBA player like LeBron James made the companies take a whole new look at the return on investment they were getting on the cash they were handing to college coaches.

Soon only the high profile college coaches like Coach K at Duke and a handful of others were getting the sweetheart deals, and less-elite programs were scrambling to make up the lost revenue out of other athletic department funds. “Gone are the days,” wrote Wetzel, “when athletic departments could expect a shoe company to underwrite a significant part of a coach's compensation package.”

Then the schools started getting uncomfortable with the direct relationship between the shoe companies and their coaches. Texas A.D. DeLoss Dodds is credited by many accounts with being the first to approach the apparel manufacturers directly to strike a broad-based deal for the school, and take control of how that cash got distributed. Today the university-wide, all-sports “outfitting” deal with the apparel companies is the rule. And it turns out that the days Wetzel wrote were “gone” in 2004...weren’t gone for long.

In 2010 it was reported that Michigan had the nation’s largest apparel deal, an eight-year contract for $66.5 million with Adidas, an arrangement that netted UM an upfront $6.5 million signing bonus for bolting their Nike affiliation. North Carolina signed a 10-year $37.7 million deal with Nike in 2008. Many other schools are in agreements with apparel companies that bring in at least $2-3 million per year.

Ohio State outsourced their entire sports marketing portfolio to IMG College in a 2009 deal that includes stadium advertising and other sponsorships as well as apparel, and will bring $110 million to the university over 10 years. As far as “underwriting a significant part of a coach’s compensation”, well...you tell me. OSU’s $4 million a year deal with Urban Meyer is allocated as follows: $700,000 is “base compensation”...$1.85 million for “media, promotions and public relations", and $1.4 million under “apparel,shoes, equipment”.

Now, no one is buying the notion that Ohio State is paying Meyer two and a half times as much to do TV, radio and Internet shows (“media, promotions”) as they are to coach the football team. But his cash for the apparel and shoe deals is twice the amount of his base compensation...and I think we can assume that Meyer’s $1.4 million in that category is being paid pretty much directly from the Nike contract (possibly among others). I call that significant.

A cursory search found several other instances of current coaching contracts in which the money for shoe/apparel deals was three to four times the amount of the base contract. It may be unwise though, to put too much stock in those contract breakdowns. Nick Saban’s $5 million deal at Alabama is structured laughably, with a “base” of $225,000, (presumably for, you know, coaching), and then a “talent fee” (bundling all his compensation for TV, radio, Internet, promotions, appearances, and apparel/shoe money), of $3.93 million a year. Ha.

I guess the risk to schools of relying on outside sponsors to pay such a large share of the coaching salaries is that - like they did with the basketball coaches’ shoe deals a decade ago - what Nike giveth, Nike can also take away...as soon as their ROI models tell them to.

“Example is the school of mankind, and they will learn at no other”, said Edmund Burke a few years back. The best coaches they say, are teachers first. What kinds of lessons are our student athletes learning at the example of their coaches? For one, that there is some extra money to be made in equipment and apparel. Should we be surprised when they act accordingly?

Sonny Vaccaro and the Ed O’Bannon Lawsuit

One potential bubble-burster for the NCAA and college athletics would be a victory for the plaintiffs in O’Bannon v. NCAA, a lawsuit filed in 2009 by former UCLA Bruin basketball player Ed O’Bannon, which has since been joined by several other high-profile plaintiffs including Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell.  The case is based on what O’Bannon and others claim involves a restraint of trade under federal antitrust law, owing to the NCAA’s restriction of their ability to profit in perpetuity from the use of their likenesses (for example, in video games) after they are finished with their college playing careers. An excellent backgrounder from PBS Frontline summarizes:

The case is based on what O’Bannon and others claim involves a restraint of trade under federal antitrust law, owing to the NCAA’s restriction of their ability to profit in perpetuity from the use of their likenesses (for example, in video games) after they are finished with their college playing careers. An excellent backgrounder from PBS Frontline summarizes:

Before they can compete in a Division I sport, athletes must sign every year a seven-page Student-Athlete Statement, a form that states they are amateurs and give up any compensation for playing and that they promise to abide by all the rules in the NCAA Manual, including those dealing with amaturism and the use of athletes' images. According to the lawsuit, student-athletes "forgo their identity rights in perpetuity" in part because they are required to sign this document.

More good info on the case here from Michael McCann at Sports Illustrated.

Leading the forces for the plaintiffs is Sonny Vaccaro, which at first glance is a head-scratcher, if one is at all familiar with the man who made his name as the pioneer of shoe contracts, and who has been vilified for years as an exploiter of kids and a tool of corporate interests. The skepticism surrounding his involvement with the O’Bannon cause was akin to what you might find if Charlie Sheen went crusading in the war on drugs. But Vaccaro (pictured) is working without pay, and his sincerity really does seem beyond reproach. A shot at redemption perhaps. Good profiles of the Pittsburgh native and Youngstown State grad here, here, and here.

At issue is the NCAA’s increasingly shaky defense of its entertainers and performers as amateurs, what Branch characterized in his Atlantic piece as a billion dollar edifice...hanging on the consent of a few young volunteers. The NCAA has fought tooth and nail the idea that its members’ athletes are “employees” of this vast money-making enterprise. If they were, among other liabilities, the organization might be found responsible for work-related injuries under workers compensation statutes. Imagine that.

The above link to Frontline brings you up to date with the latest developments in the case.

---

If a situation can’t go on forever the way it is currently configured...it won’t. Change will come. Bubbles will burst. Or so we are conditioned to think.

This particular bubble...the athletics one within the greater higher education bubble...has been remarkably resistant to change, however. The disconnect between college athletics and the greater university mission is, after all, not a new development. Thirty years ago, complaints could be heard about the crass commercialization of the games...the erosion of amateurism...the corruption of the sport by agents and television money. So we’ll see...

We’ll see how long our higher education establishment will tolerate coaches making triple the salaries of college presidents. And how long they’ll allow a cartel-like bureaucracy to oversee a billion dollar industry while artificially suppressing the price of the labor on which it is built.

We’ll find out how long financially strapped, taxpayer-supported universities will continue to require non-athlete students to subsidize athletic departments unable to support themselves. And we’ll see how long the NCAA will continue to claim that the workers generating the revenue for this enterprise are not in any legal sense its employees, and thus entitled to the protections of employee status.

It remains to be seen which will do more damage to our system of college athletics. If the bubble finally bursts...or if it doesn’t.

---

on Twitter at @dwismar

Dan’s OSU Links and Resources

---

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)