Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Browns Game Vault: 12/24/50. QB Otto Graham and HC Paul Brown’s Defining Moment

Browns Game Vault: 12/24/50. QB Otto Graham and HC Paul Brown’s Defining Moment

Our histories are defined by specific moments- shared or otherwise. Each of us views our lives through the prisms of our marriages, the birth of our children, and the deaths of loved ones. Various other celebrations and tragedies add to the list of notable occasions that help shape and define our experience. Our outlook, our tastes, our preferences. These instances from the past even affect the way we experience future moments.

Our histories are defined by specific moments- shared or otherwise. Each of us views our lives through the prisms of our marriages, the birth of our children, and the deaths of loved ones. Various other celebrations and tragedies add to the list of notable occasions that help shape and define our experience. Our outlook, our tastes, our preferences. These instances from the past even affect the way we experience future moments.

Let’s look at a few types of moments. For fun, let’s draw some parallels to classic rock music, and then consider an example for each involving our Cleveland Browns experience.

~

While we experience any given moment to some degree within its general context, once in a while a significant point in time seems to arrive without advanced warning. Unexpected, shockingly bad things may fall into this category, like an episode of senseless violence. I suppose positive things may occur in this manner, as well. I don’t know- maybe like if you won the Publishers’ Clearing House prize! I know, we’ve all had that happen.

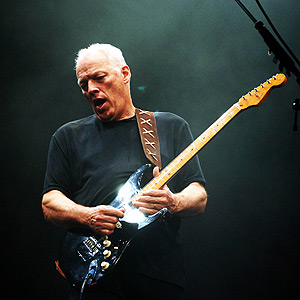

For a classic rock parallel, we might consider an exquisite moment of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb”.

For a classic rock parallel, we might consider an exquisite moment of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb”.

The song’s soaring soundscape reaches the point to where it slowly morphs into a pounding beat as the second, song-ending guitar solo approaches. David Gilmour announces that solo with a sublime, harmonic first note. AHHHHH… (that’s five H’s, on the 5-H scale)

The Cleveland Browns have not had too many sublime, harmonic moments recently. I’d say kickoff and punt returns qualify- they can kind of come out of the blue. Let’s place some of the famous returns by the Browns of days gone by here. Like Homer Jones’ kick return against the Jets in the first Monday Night Football game in history, back in 1970. Or Eric Metcalf’s two punt returns in one game to beat Bill Cowher’s Steelers. Or any of Joshua Cribbs’ kick returns for touchdowns, before he died.

~

Some moments act as a watershed, marking the division of two separate periods. For example, such a moment may be when a student finally graduates and  has earned a degree. Commencement came as no surprise; in fact, it may have seemed like it would never come. Still, the time before the watershed moment is separate and distinct from the time after. Before: spend money. After: pay off the debt.

has earned a degree. Commencement came as no surprise; in fact, it may have seemed like it would never come. Still, the time before the watershed moment is separate and distinct from the time after. Before: spend money. After: pay off the debt.

Consider the original recording of “Layla”, by Eric Clapton, Jim Gordon and Duane Allman. The song features Clapton’s frantic, panicked blues riff – until the piece winds down to a halt, and Gordon’s steady piano movement takes over. That point in between those sections of that song is the watershed moment. Awesome, I know. (My mild disappointment on hearing a post-rehab Clapton telling me and 15,000 fellow concertgoers circa 1983 that “we’re not going to do any blues numbers tonight” was kind of a watershed moment for my view of that guy, I must say.) Photo to the right shows Clapton with the subject of the song, Patti Boyd. Google that story, if you care to-

An instance of a watershed moment with the Cleveland Browns may well be the current change in ownership from Randy Lerner to Jimmy Haslam. Most fans seem certain that the entire vibe and mode of operation of the franchise is about to change. We’ll see.

~

Many compelling moments occur as a release - after a buildup, or a period of increasing tension. A pregnancy test comes to mind. …Yes, that works, on multiple levels.

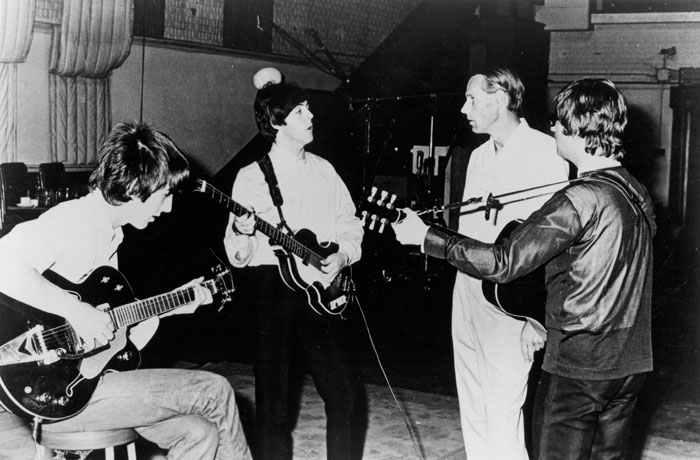

“A Day in the Life”, recorded by The Beatles with George Martin, fits the bill here. There are two orchestral crescendos; the first one is kind of a ‘watershed’ between John Lennon’s melancholy thoughts of a guy getting in a car wreck and Paul McCartney’s playful recollection of waking up when he was younger. The second crescendo comes at the end of the song, building even more tension. Finally: the release is an E-major chord, played once, simultaneously on four pianos and a harmonium (a type of organ). (Yes, I did look that up.) For over forty seconds, the chord is kept at the same volume by Martin’s manipulation of the recording level. It is said that by the end of the length of that chord, ambient sounds also are amplified, like the squeak of a chair, rustling papers, and the whirr of a distant ceiling fan. Maybe- I never have heard the fan, in particular. And I have tried. But that final chord has tremendous impact.

“A Day in the Life”, recorded by The Beatles with George Martin, fits the bill here. There are two orchestral crescendos; the first one is kind of a ‘watershed’ between John Lennon’s melancholy thoughts of a guy getting in a car wreck and Paul McCartney’s playful recollection of waking up when he was younger. The second crescendo comes at the end of the song, building even more tension. Finally: the release is an E-major chord, played once, simultaneously on four pianos and a harmonium (a type of organ). (Yes, I did look that up.) For over forty seconds, the chord is kept at the same volume by Martin’s manipulation of the recording level. It is said that by the end of the length of that chord, ambient sounds also are amplified, like the squeak of a chair, rustling papers, and the whirr of a distant ceiling fan. Maybe- I never have heard the fan, in particular. And I have tried. But that final chord has tremendous impact.

A Browns analogy? The final game of 2002 comes to mind. HC Butch Davis had his troops fighting for a playoff spot. They were attempting to beat the Atlanta Falcons, overcoming Dwayne Rudd’s blowing the season opener by removing his helmet before time had expired. The decibel level was befitting of Cleveland Browns fans’ legendary status. The game was an anxiety-packed struggle, until… RB William Green broke into the clear on an off-tackle running play. The crowd expelled the pent-up energy as broadcaster Jim Donovan hollered, “RUN, WILLIAM, RUN!” (channeling Forrest Gump). Green took it all the way! Sure, it took a goal-line stand from the defense late in the game to seal the deal, but Green’s run came while the Falcons' playoff status was still in doubt (during the game, they would learn that they were in, due to New Orleans’ loss, prior to the goal-line stand). The Browns’ status as a playoff team seemed assured as Green scored.

**

One seldom hears the name of Otto Graham any more. Years ago, I’d at least hear his name when reading or listening to discussions about the greatest  quarterbacks ever. I realize he played more recently than Graham, but it’s interesting that when the top running backs of all time are noted, Jim Brown still gets his due respect. Not too long ago, he was commonly accepted as the best football player ever. (Then, you’d get, “And he was an even better lacrosse player!”) Other backs often get the #1 ranking these days, but #32 is always in the conversation. (I don’t mind that he isn’t considered #1. He quit in his prime. His choice, but it was he who opened himself up to questions about his all-time ranking.) Otto Graham gets left out of a lot of “best ever” conversations.

quarterbacks ever. I realize he played more recently than Graham, but it’s interesting that when the top running backs of all time are noted, Jim Brown still gets his due respect. Not too long ago, he was commonly accepted as the best football player ever. (Then, you’d get, “And he was an even better lacrosse player!”) Other backs often get the #1 ranking these days, but #32 is always in the conversation. (I don’t mind that he isn’t considered #1. He quit in his prime. His choice, but it was he who opened himself up to questions about his all-time ranking.) Otto Graham gets left out of a lot of “best ever” conversations.

That is too bad. At the helm of the innovative vertical, deep-strike offense of Paul Brown, Automatic Otto helped to revolutionize the NFL, and bring it closer to the game it is today.

Let’s hearken back to 1943. Paul Brown had risen as a dominant high school football coach in Ohio, most notably at Massillon High School. He had made the move to big-time college football when he accepted his dream job as head coach of The Ohio State Buckeyes. He’d led the Bucks to a 6-1-1 record in ’41- the year that the Japanese forced the U.S. into WWII by bombing Pearl Harbor, in December. The Bucks’ only loss was to a Northwestern team that featured star tailback Otto Graham. 1942 was when the coach had perhaps reached the pinnacle of his profession, having led Ohio State to its first national championship (many considered the college game to be superior to the rough and tumble pros). By 1943, Paul Brown had set his sights on building a dynasty in Columbus, Ohio.

But as John Lennon would later write, life is what happens when you are making other plans.

The 1943 season was bitterly disappointing for Brown. Many schools in the Big Ten had an advanced military officer training program. This was where men could play football for a year, while enrolled in such a program. Ohio State did not offer that, and he lost most of his older, experienced players. Yet Brown was forced to play a full conference schedule, where his team was sometimes overmatched. He often complained about the uneven playing field, and began to get a little bit of a backlash due to his brooding while young men were dying abroad.

Back in 1939, Brown had registered for the military draft. As a family man, there was little thought that he would in fact be drafted. However, in early 1944, the Massillon draft board reclassified him, in effect making him more eligible. Ohio State petitioned for a deferment for Brown, only to drop it at his request. He received his commission: Great Lakes Naval Training Base, just north of Chicago.

Brown was battalion commander, and head football coach. The admiral in charge assured Brown that he was committed to allowing him to assemble a good football team- a promise that would be kept.

Meanwhile, various groups were attempting to prepare to compete with the National Football League. The NFL had a narrow fan base, and didn’t promote itself  very well. Any anyway, baseball was king. Boxing was huge, as was thoroughbred racing.

very well. Any anyway, baseball was king. Boxing was huge, as was thoroughbred racing.

Innovator and promoter Arch Ward (mastermind of such events as the baseball all-star game) was finding backers for teams that would comprise a league that he would oversee. “Mickey” McBride (right) had a majority stake in a Cleveland, Ohio franchise in the league, which would be known as the All-America Football Conference.

Cleveland already had an NFL team, the Rams. McBride had tried to purchase them five years earlier. The Rams weren’t very competitive, and had trouble staying afloat. There was a stretch of time when they played home games in a high school stadium; even those games were far from sellouts.

McBride had the wherewithal to fund his football enterprise- he owned taxicab companies in Cleveland, Akron and Canton. He owned real estate in Cleveland, Chicago and Florida. Also, a radio station, a printing company, and a race wire syndicate.

McBride’s stated goal was to start with the best coach available. Then, he would allow his coach to have the ability, to spend the money necessary to acquire the best players.

The owner had a plan, but had his vulnerabilities, as well. For starters, he didn’t know football very well. He had ties to Notre Dame, and knew Frank Leahy. Leahy was a successful coach. So, McBride set his sights on signing him to be the first coach of his football team. Leahy actually gave him his oral agreement. Alarmed, Notre Dame balked. McBride had two sons enrolled at the school, and decided not to make waves- he withdrew his offer to Leahy. Not knowing whom to hire, he approached John Dietrich of The Cleveland Plain Dealer. Dietrich quickly sold McBride on Paul Brown. McBride discussed this with Arch Ward, who knew Brown from Great Lakes. The prospect of Brown in his league enthused Ward, who offered to broker the deal.

Ward visited Brown at Great Lakes, and laid out the offer. The league, the team, the opportunity. Brown had never had any interest in professional football. The quality of football wasn’t as good, and Cleveland had not supported the Rams very well. He would consider the offer- but first, he wanted to give Ohio State the opportunity to take him back.

The Ohio State athletic director at the time was Lynn St. John. There was a history of uneasiness between St. John and Brown, dating back several years, which was now about to explode into an open feud. Brown disclosed Arch Ward’s proposal, which St. John could not match. Some view this as being welcomed by St. John, who began to campaign against the “money grubbing” Brown. Brown’s chances to return to Columbus dimmed; he began to look at other universities as possible landing spots. Mickey McBride increased his offer. Brown accepted.

Paul Brown was an all-or-none guy; he immersed himself fully in the task of developing a championship football team in Cleveland. The first and foremost player he wanted: former foe, Otto Graham. Graham had been drafted by the Detroit Lions, but Brown made him an offer that began paying him while he remained in the military. Brown had his man.

Brown proceeded to sign several of his ex-Buckeye football players who began returning after the war ended in 1945. Lou Groza, Dante Lavelli, Lin Houston…  Most had college eligibility remaining. Notably, Paul Brown’s rule as a college coach was that his players earn their degree as their first priority. Columbus was in an uproar- although times were now different. These were no longer boys. They were men, returning from war, looking to earn a living.

Most had college eligibility remaining. Notably, Paul Brown’s rule as a college coach was that his players earn their degree as their first priority. Columbus was in an uproar- although times were now different. These were no longer boys. They were men, returning from war, looking to earn a living.

The Rams bailed and left Cleveland, rather than compete with the new AAFC squad- a team that eventually would be named the Cleveland Browns.

Paul Brown’s innovations and standards are legendary, and he developed many of them in Cleveland. He also racially integrated the team during the era when Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby were breaking the color barrier in baseball. Apparently, Brown was not making social statements; he was interested in fielding the finest football team in the country.

The Cleveland Browns dominated the AAFC. So much so that the home crowds were variously strong at times, and weak at others (Cleveland was not Browns Town, yet). It almost seemed that the fans were disinterested in a football team that was so good.

There was talk of a merger with the NFL. Eventually, what that boiled down to was an assimilation in 1950 of a few AAFC teams into the NFL, including  Cleveland. The more established NFL was looking to assert its dominance over the flashy, throwing Browns- and was shocked to find that as always, Cleveland steamrolled through its schedule- no matter which league was on it.

Cleveland. The more established NFL was looking to assert its dominance over the flashy, throwing Browns- and was shocked to find that as always, Cleveland steamrolled through its schedule- no matter which league was on it.

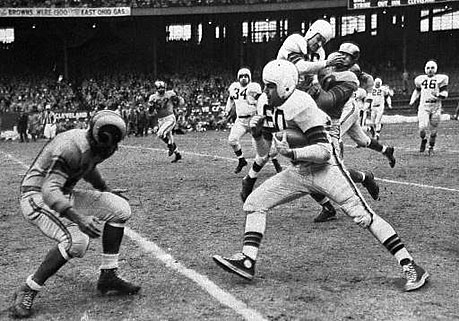

The season culminated in the NFL title game at Cleveland Stadium between the Browns and the Los Angeles Rams- Cleveland’s former team. In front of (only) 29,000 fans, in frigid weather, the game was a see-saw affair. The Rams took the first lead, and the Browns played catch-up for most of the game. Late in the 4th quarter, Otto Graham moved the offense to within range of a Lou Groza field goal- only to fumble the ball away. With three minutes to go, the Rams had the ball and the lead.

Graham was sure that when he left the field, Paul Brown would be in his face, chewing him out for causing the loss. Instead, the militaristic Brown broke from his character as he approached Graham. He patted his quarterback on the shoulder and reassured him that the defense would get the ball back. They’d win the game yet.

Graham later would remark that words could not convey how Brown’s words gave him the confidence he needed after the fumble. The Browns did get the ball back. Graham ran the ball three times, and threw once, to give Groza the chance to win the game with 28 seconds left.

Groza’s (right, showing his shoe to McBride) straight-ahead, flat-toed kick was good (he never missed a big kick), to complete one of the biggest ‘upsets’ in NFL history. An upset? Sure, if you  believed the arrogant old guard of the traditional NFL. The victory was a testament to coach Brown’s ability to form, develop and motivate a team, and to the all-time great quarterback, whose career was partly defined in this instant.

believed the arrogant old guard of the traditional NFL. The victory was a testament to coach Brown’s ability to form, develop and motivate a team, and to the all-time great quarterback, whose career was partly defined in this instant.

We'll call it both a watershed, and a huge release of tension.

Meanwhile, colleges from Minnesota, to USC, to OSU, and Stanford were commonly known as having interest in hiring Paul Brown as their head coach. In front office news, Mickey McBride was involved in hearings in front of the Kefauver Committee in the U.S Senate (right). It was the nation’s first major crackdown on organized crime.

It was a time of pivotal moments.

Thank you for reading.

Sources included Paul Brown: The Rise and Fall and Rise Again of Football’s Most Innovative Coach, by Andrew O’Toole; Tales from the Browns’ Sideline by Tony Grossi; PB-The Paul Brown Story by Paul Brown; Wikipedia.

Below- Graham, in the process of winning the 1950 NFL title game.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)