Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Browns Game Vault: 9/1/93. The Apex of the Kosar/Belichick Era

Browns Game Vault: 9/1/93. The Apex of the Kosar/Belichick Era

Browns fans were ready to start winning again. Head coach Marty Schottenheimer’s title-contending roster was aging. The annual tinkering of the roster with the intent to beat Denver Broncos’ QB John Elway had resulted in a last-place team by 1990. The architect of the offense, Lindy Infante, was long gone. As was Schottenheimer himself- and finally, his replacement, Bud Carson.

Browns fans were ready to start winning again. Head coach Marty Schottenheimer’s title-contending roster was aging. The annual tinkering of the roster with the intent to beat Denver Broncos’ QB John Elway had resulted in a last-place team by 1990. The architect of the offense, Lindy Infante, was long gone. As was Schottenheimer himself- and finally, his replacement, Bud Carson.

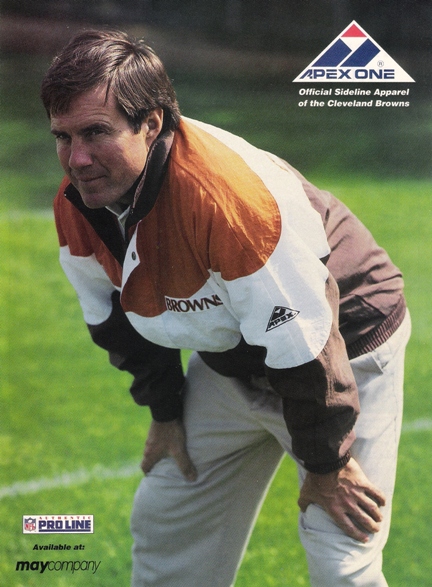

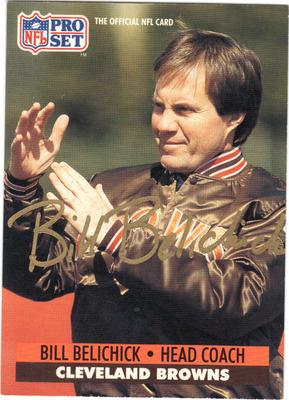

Two years earlier, Modell had interviewed young Bill Belichick before signing Carson. In 1991, he tabbed the Bill Parcells disciple – a man in his late 30s whom some said was the brains behind the powerhouse New York Giants defense of LB Lawrence Taylor. Noteworthy were the referrals and compliments Modell received from such luminaries as Indiana Hoosiers basketball coach Bob Knight. Public validation was at the heart of Modell’s world- it was what he was all about.

Notable football men- including his father, a former coach and scout- proclaimed that Bill Belichick was ready to be a great NFL head coach. We fans seemed to barely notice the common rejoinder: “…if preparation and hard work are how you measure it…” What we fans knew was that we had a historically bad (up to then) team, and here was the smart young coach of the best defense in the league, coming to restore greatness to the shores of Lake Erie. Through his father, he had been steeped in the ways of football his entire life. He understood our winning history, and how deeply the Browns are woven into the fabric of Ohio.

winning history, and how deeply the Browns are woven into the fabric of Ohio.

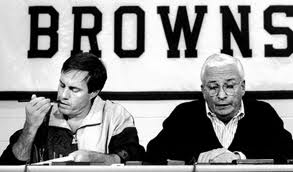

Early on, we began to see our head coach begin to behave like an ass. The media hated it, but a lot of fans like me weren’t concerned about that. I could not have cared less if Tony Grossi got his feelings hurt by the leader of our next NFL playoff team. Just win.

But it was odd, the way the new coach went out of his way to show people he couldn’t care less for them. I think I noticed after the first game of 1991, at home against the Dallas Cowboys. Injuries had decimated the Browns, and QB Troy Aikman carved them up.

There really was nothing to be ashamed of, losing to the up-and-coming Cowboys. Then again, shame was not a trait that one would ascribe to Belichick. In the post-game press conference- a time when NFL coaches hang in there for a good while and take questions- he tried to escape after the third question. I think he earned the nickname, “Mumbles” on that very day.

Thereafter, he willfully dissed the press. He was known to hold press conferences while riding an exercise bicycle, or while eating lunch- and belching. A workaholic, he had his coach’s television show taped at 5:50am. He’d step away from his brief night’s sleep on his office cot, and tape the show wearing an old sweatshirt- even though his wife would send him sweaters, in vain. He’d mumble through the show while yawning. The clear message was that the media wasn’t worthy of his time. They weren’t smart enough to understand, anyway. Same went for the fans. He reportedly once said, “I don’t give a damn what the fans think.” The media would begin to turn on him, and he didn’t care.

They weren’t smart enough to understand, anyway. Same went for the fans. He reportedly once said, “I don’t give a damn what the fans think.” The media would begin to turn on him, and he didn’t care.

Over the next couple seasons, Mumbl- er, Bill Belichick went about the serious business of turning over the aging Browns’ roster. Apparently, the team had grown soft, and was now suffering from culture shock under the relatively extreme physical and mental expectations of the coach. Training camp and practices were physically grueling. There was constant roster turnover, and the coach’s withdrawn nature fostered confusion within the team. But through some adequate (not great) drafting- and an infusion of some ex-Giants, the team was becoming transformed.

After a 6-10 record in 1991, and a 7-9 mark in 1992, it was time for the team to take a step up and reach the playoffs. Prior to the season, veteran inside linebacker (and one-time Buckeye) Pepper Johnson was signed away from the Giants. Oversized defensive lineman Jerry Ball was lured from the Detroit Lions, and physical, yet mobile-as-a-guard Steve Everitt was drafted out of the University of Michigan in the first round to anchor the center position. These moves were to bolster the team up the middle, which is one of the tenets of a Bill Belichick football team.

Also garnering attention around the league was the Browns’ signing of six year veteran QB Vinnie Testaverde from the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He was the embattled five year veteran of a bad Bucs team that was trying to lift itself out of its expansion-era doldrums (yes, very similar to these Browns). The media and fans in Florida had turned on Vinnie, and the former #1 pick wore the label of ‘draft bust’. Vinnie was ostensibly signed to back up Bernie Kosar.

Vinnie was ostensibly signed to back up Bernie Kosar.

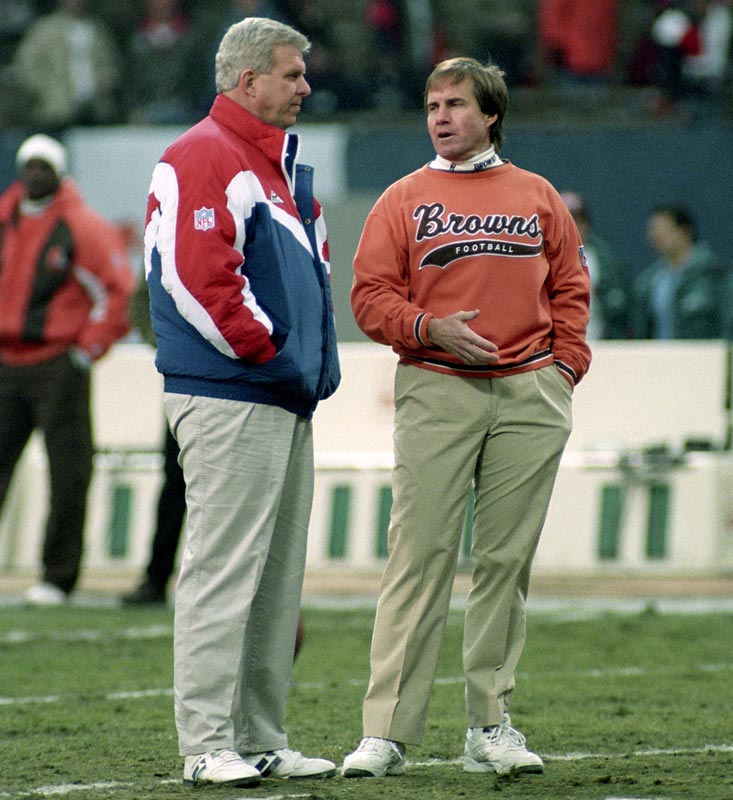

After an opening day win against the Cincinnati Bengals, the Browns remained in Cleveland for Game Two, a Monday night affair vs. the Super Bowl contending San Francisco 49ers. The Niners had played in the NFC Championship Game the previous season, and boasted the NFL’s Most Valuable Player in QB Steve Young. His favorite target was future Hall of Famer Jerry Rice, and stopping that offense was a tall task.

Monday Night Football in 1993 may not have been more hyped than it is today, but it arguably commanded the attention of a larger proportion of the sporting world. The media flocked to the games. Even Ohio media from towns such as Columbus and Dayton set up announcer tables outside Cleveland Stadium the evening of the Niners game, running their own pre-game analysis and advertising.

On football’s biggest stage, the Browns had a chance to prove to the world that they were back. They received the opening kickoff, and on the first play from scrimmage, Kosar took the snap and dropped back. They caught the Niners by surprise, as wide receiver Michael Jackson sprinted near the right sideline past the defense and was wide open. Kosar’s pass was on target- and shot right down though Jackson’s hands, at his midsection, falling harmlessly to the field. Viewers sat there thinking: Jackson could have caught that ball with his elbows/Maybe he should have tried that/Oh well, that was our chance to catch them by surprise/We don’t have the kind of offense that can withstand bowing opportunities like that.

Incredibly, another first quarter touchdown was negated by a penalty. But the Browns would move the ball well all night. In fact, other than those miscues, almost everything else went Cleveland’s way. They blocked a field goal try. Jackson redeemed himself by catching a 30 yard pass for a touchdown from Kosar. Young fullback Touchdown Tommy Vardell converted fourth down and short twice, out of the “Jumbo” formation (Belichick liked to ram the ball straight into the line on short yardage plays.)

The Browns defense dominated the formidable Niners throughout. Rice was a non-factor, and Young was harassed throughout the game. S Eric Turner, LB Clay Matthews and CB Selwyn Jones each had an interception. Jerry Ball sacked the 49ers quarterback in the fourth quarter, forcing a fumble in Cleveland territory. LB Michael Dixon recovered the ball at the Browns’ 33 yard line, snuffing out a San Francisco scoring threat. It all added up to a 23-13 Browns win that wasn’t really that close.

The Browns, six point underdogs entering the game, emerged with a 2-0 record to start the season. The fortunes of the team were looking up. It was beginning to look like this Bill Belichick guy was going to work out just fine. Winning pushed aside any animosity fans may have had over his dour, acerbic manner. For now, at least. Next week, we’ll take a peek at how the next six weeks would change the dynamic between the coach, his quarterback, the backup, and the fans.

Thank you for reading. Sources included The Cleveland Browns website, the Browns game database on cleveland.com, pro-football-reference.com, Wikipedia, the Associated Press, and a Google-able Harvard Business School paper composed by John R. Wells and Travis Haglock dated August 10, 2005.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)