Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Recovering "The Fumble," 25 Years Later

Recovering "The Fumble," 25 Years Later

No matter how much we may prefer Jim Brown or Bob Feller in the role, Cleveland sports’ most suitable folk hero remains Earnest Byner, the man who—25 years ago—became famous not so much for how he failed, but for how close he came to succeeding. Of all the footballs to ever slip from a player’s fingertips in all the years and at every level in which the game has been played, only one was transcendent enough to require and maintain its own definite article. By no coincidence, “THE Fumble” isn’t just some sad lowlight in Cleveland Browns history—it’s become a sort of poetic, pop-cultural reference point for a much broader piece of the human experience. Oh, cruelest of heartbreaks, Byner be thy name.

No matter how much we may prefer Jim Brown or Bob Feller in the role, Cleveland sports’ most suitable folk hero remains Earnest Byner, the man who—25 years ago—became famous not so much for how he failed, but for how close he came to succeeding. Of all the footballs to ever slip from a player’s fingertips in all the years and at every level in which the game has been played, only one was transcendent enough to require and maintain its own definite article. By no coincidence, “THE Fumble” isn’t just some sad lowlight in Cleveland Browns history—it’s become a sort of poetic, pop-cultural reference point for a much broader piece of the human experience. Oh, cruelest of heartbreaks, Byner be thy name.

Now if you’re already cringing at the thought, rest assured, this little piece is not intended to be the latest in a long line of re-visitations of that fateful play itself. We won’t be digging into whether Webster Slaughter missed his blocking assignment or how Bronco bench player Jeremiah Castille wound up as the unlikely Johnny-on-the-spot. Instead, on the occasion of its 25th Anniversary, it seems a fitting time to set aside any lingering angst from that day, and to simply give The Fumble its due as a pretty spectacular and enduring study in misfortune.

From a local perspective, it is probably at least worth noting that the 1987 AFC Championship Game was played at Denver’s Mile High Stadium on January 17, 1988. On the grand timeline of Cleveland sports history, then, it falls almost perfectly in-between the landmarks of the Browns’ last championship (December 27, 1964) and the appearance of that same franchise—now known as the Baltimore Ravens—in Super Bowl XLVII this weekend. In that respect, “The Fumble” also serves as a sort of axis point for almost three generations of hard luck Cleveland sports fans. Even on a misery reel that includes the obligatory inclusions of “Red Right 88,” “The Shot,” and Game 7 of the 1997 World Series, it’s “The Fumble” that seems to best encapsulate everything that is both painful and oddly captivating about life on the losing side.

As best as I can tell, there’s a three-part formula to explain why this particular fumble from the Reagan administration still remains more famous than all the rest (with perhaps only Mark Sanchez’s recent “butt fumble” in contention at this point).

I. The Circumstances

I. The Circumstances

There has been no shortage of memorable turnovers in the annals of the NFL postseason. Some are the consequence of foolishness, like Leon Lett’s infamous fleecing by Don Beebe in Super Bowl XXVII, while others are just the result of an excellent defensive effort, like Eric Wright’s strip of Chris Collinsworth at the 5-yard line in Super Bowl XVI. Neither of those plays, however-- nor just about any other postseason cough-up you can track down-- involved the level of drama that Byner’s did. Having overcome a 21-3 deficit, Cleveland is just 8 yards away from tying the game at 38 with 1:12 remaining. On the line: A trip to the Super Bowl and redemption from a heartbreaking defeat at the hands of the same Denver squad a year earlier. Byner, one of the heroes of the comeback, has already scored two touchdowns in the second half, and he takes the handoff from Bernie Kosar with daylight guiding him to apparent paydirt again. Crossing the 2 yard-line, six feet from glory, Byner plants his foot and attempts a juke too elude Castille-- the last line of defense. With his momentum still carrying him forward, Byner's body finally comes to rest, knees first, right on the chalk of the goal line. He has reached his destination, but somehow, his hands are empty.

Of course, even in the split second that Byner had to process what had just happened, there was still reason for optimism. Not every fumble is a turnover, after all. In fact, the Broncos had fumbled twice in the same game, but managed to cover up the loose ball in both instances. In the mad scramble at the 2-yard line, there was at least a 50/50 chance a Brown would come away with the football, giving Kosar and company new life, still on the doorstep of overtime with a 3rd-and-goal to go. And yet, oddly, it didn’t feel like a 50/50 chance at all. The tragic elements were all there and the outcome seemed determined long before the referees managed to find Jeremiah Castille with Byner’s lost parcel in his clutches. It may as well have been the halfback’s heart.

To fumble the ball at the goaline on a potential tying score in a conference championship game… that didn’t happen every day in 1988. And it hasn’t happened a hell of a lot since.

II. The Flip Side to “The Drive”

II. The Flip Side to “The Drive”

As famous sports moments go, few events from entirely separate games AND seasons are so unavoidably linked as The Fumble and “The Drive”—John Elway’s career-making two-minute drill from a year prior. On the surface, the reasons are obvious enough. The 1986 and 1987 AFC Championships both featured the Denver Broncos beating the Cleveland Browns in thrilling, down-to-the-wire games, so mentioning one after the other is just practical. What doesn’t get recognized as much, however, is how these two events have also amplified each other over the years. Without question, people would still remember Elway’s heroics, and the aforementioned circumstances of The Fumble would assure Byner's legacy, as well. But as a tandem, “The Drive” and “The Fumble” become something far greater. Rather than isolated, famous highlights from a bygone era, they form the perfect yin and yang of what Wide World of Sports used to call “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.”

Alone, “The Drive” works quite nicely as a tale of triumph in the face of incredible odds. Trailing 20-13 in a hostile environment, pinned back at his own 2 yard-line with 5 minutes to play, Elway—the gun-slinging hero—leads his troops on a systematic march down the entire length of the field, culminating in a beautiful touchdown pass arched just over the outstretched arms of the enemy. Victory! (No one remembers that “The Drive” only tied the game. Such details scuff up the narrative).

Going back to early Greek dramas, though, the only thing as entertaining as a great comedy is a tragedy to serve as its counterpart. Thus, The Fumble was a godsend. Just one year after Elway’s happy tale of success starting from the 2-yard line, we have defeat met at the very same spot on the field. Kosar and the Browns, seemingly on the verge of re-enacting Elway’s script, instead flip it over entirely. If the football-loving public ever wondered what it might have been like if the underdog's spiritied heroics had not been justly rewarded, we now saw it in the absolute anguish on the Cleveland sideline. Rather than playing background scenery to a hero’s glory like in The Drive, the Browns were now the focus of the attention, with Byner as the relatable protagonist and Elway as a secondary character.

Without “The Drive,” The Fumble doesn’t resonate quite as dramatically. And without The Fumble, The Drive doesn’t have the counterweight necessary to keep it afloat in the consciousness of an ADD pro sports culture.

III. Being Earnest

III. Being Earnest

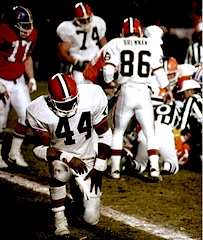

Lastly, and maybe even most importantly, The Fumble is worth remembering for Earnest Byner himself. It’s fairly common knowledge at this point that Byner—a class act off the field-- had performed admirably in the game up to that point, and virtually no Browns fan still holds a grudge against him or questions his effort on that final play. Even those who cursed his name that day in the heat of the moment are likely to remember Byner’s fumble—in retrospect-- as a terribly sad moment, rather than an infuriating one. This is largely because the now iconic images of #44—frozen in anguish at the goal line as Brian Brennan consoles him—have come to inspire as much empathy as just about any other in-game sports image of the past century. And that’s not just empathy from heartbroken Cleveland Browns fans, mind you. For the vast majority of people who’ve seen the images of The Fumble’s aftermath—be it hardcore football fans or casual observers—it’s the universally understandable feeling of personal disappointment that resonates. The unique pain that comes from falling short, from letting yourself and others down, despite your best efforts. Regardless of the circumstances, regardless of the weird dual history with the Broncos game from a year earlier, it’s Byner body language that day—the look on his face even through a helmet—that keeps the play so vivid in our minds.

Anyone who has ever loved and lost can't help but be a bit of a Byner fan. And while Earnest himself went on to earn his fair share of redemption by scoring a touchdown in a Super Bowl victory with the Washington Redskins several years later, it doesn’t seem to diminish our feelings in watching that grainy footage from a frigid day at Mile High. The Fumble—much as we might like to forget it sometimes—is every bit as integral to our modern American sports lore as the sight of an Elway, Jordan, or Jeter raising their championship trophies. If we only watched sports to see glory, it wouldn’t hold our interests for long. Entertainment works best by reflecting many different aspects of reality and crystallizing them a bit. We care more when we can relate. And 25 years later, we can all still relate to Earnest Byner from time to time.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)