Browns Archive

Browns Archive  A Compelling and Complicated Man

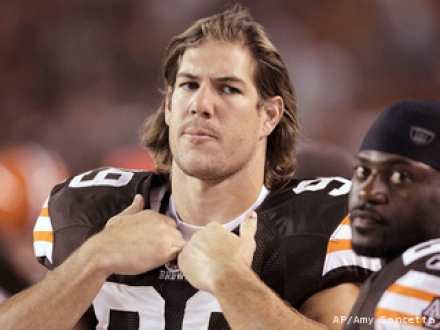

A Compelling and Complicated Man

The announcement barely earned a mention in the Plain Dealer last week but Scott Fajita, the former linebacker for the Cleveland Browns, has officially retired. He signed a one-day contract with the New Orleans Saints so that he could officially retire from the franchise that wouldn't pay him enough to keep from becoming a free agent and signing with the Browns. He never much liked the Browns anyway, just their money.

The announcement barely earned a mention in the Plain Dealer last week but Scott Fajita, the former linebacker for the Cleveland Browns, has officially retired. He signed a one-day contract with the New Orleans Saints so that he could officially retire from the franchise that wouldn't pay him enough to keep from becoming a free agent and signing with the Browns. He never much liked the Browns anyway, just their money.

Fujita, for reasons that extend well beyond anything he's done on the field, has become one of football's more compelling personalities. Usually thoughtful, often combative, Fujita seems to be coming to the role of the passionate advocate as his on field career ends. It started with his front and center role in the labor dispute between the owners and players. It got its sea legs when he found himself engulfed in the maelstrom that surrounded the Saints' bounty scandal. It's taken wing on a variety of social issues, from player safety to gay marriage.

Admittedly I've not been the biggest fan of Fujita owing to in my view the destructive role he took in helping prolong the NFL lockout. Sucked into an ill-conceived strategy by NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith that it was better to litigate than negotiate, Fujita and players like former teammate Drew Brees helped sell the strategy to the rank and file that failed miserably. By believing they could force the owners' to withdraw their demands for various concessions by first decertifying and then suing under anti-trust laws, the union essentially refused to negotiate until it became clear that the courts would offer no relief or even negotiating leveerage. While this helped lengthen the overall dispute significantly, when it failed it helped get a deal done that was there for the taking months prior.

Fujita was on the wrong side of that issue and the damage it did to fringe players who lost real money and opportunity has mostly gone unnoticed. But it did occur and Fujita owns part of that legacy.

The other thing about Fujita is that I initially saw him to be mostly a phony when it came to issues about player safety. What's probably more accurate is that he's sincerely conflicted on the subject and he's let that conflict at times blunt the noble attempts of his efforts. Fujita, like other players, want to lay the league's sorry record on concussions at the feat of NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and yet see no contradiction as they unceremoniously criticize Goodell every time he punishes someone like James Harrison for trying to tackle opponents with his head.

Then there's what took place in New Orleans and how that impacts on Fujita's attempts to make the game safer.. Fujita essentially turned a willful blind eye to the actions of his own teammates who were running a bounty system designed to put players from other teams (or, as I like to call them, Fujita's union brothers) out of commission.

It's hard to square Fujita's role as a team leader in New Orleans with the fact that he did nothing to stop the bounty program. It's tough to claim the safety higher ground if you don't try to stop deliberate head and knee hunting by your teammates. Even if that atmosphere was fostered by the coaching staff, like Gregg Williams, and that does appear to be the case, Fujita didn't stand up to them either. Would taking a stand have been difficult for Fujita under those circumstances? Most certainly. But that's what leaders do.

There's also the inconvenient fact that Fujita brought the maelstrom he incurred over this issue on himself by admitting at the outset that while he would never participate in a "bounty" system, narrowly defined as a scheme to pay teammates who deliberately injured opponents so that they couldn't play, he did admittedly contribute to a pool to pay teammates for good, clean hits. Such a fine line, though even what Fujita was doing was in contravention of salary cap rules.

It bears mentioning too because it reflects on what makes Fujita both compelling and complicated is that his exoneration from the bounty scandal was similarly tortuous because of his own hardheadedness. Fujita wouldn't participate in the league's appeal process because he didn't feel it was fair. It was the appeal process laid out in the collective bargaining agreement he helped ratify but when it applied to him he wanted no part of it. After being placated but not accommodated Fujita eventually did participate, had the chance to tell his story and present his evidence and then was exonerated months later than he would otherwise have been.

These complications in his thinking aside, part of presenting the entire picture of Fujita is to not just acknowledge but praise his other more worthy contributions, especially to the ongoing dialogue that is earnestly trying to make the sport and society better.

Fujita, despite of or perhaps because of his past, has kept up the pressure, mostly in the right way, on player safety issues. What Fujita now seems to recognize is that the day has long since passed when we stopped viewing hard-nose football and player safety as contradictory concepts. I'd like to see Fujita be more even-handed in his approach or at least be as critical of his union as he has been of management. It's a shared responsibility and perhaps as a retiree Fujita's views will even out. But he's doing the right things now.

Then there's his advocacy on the part of gay athletes. Jason Collins, late of the Washington Wizards, came out Monday as the highest profile male athlete to declare he's gay. Someone had to go first. It won't be long before others follow.

Fujita for his part has been a passionate advocate for the rights of gays, generally, and gay athletes in particular. It is just this kind of leadership that's needed so that the specter of discrimination can be eradicated on this front.

It is simply shameful that in 2013 this country, as a matter of policy, still allows for the overt discrimination of gays. We allow those who claim a sincerely held religious belief over a decidedly unreligious topic to control the debate when all that debate is really doing is masking irrational homophobia. If your First Amendment right to free association allows you to hang with a large group of intolerant religious zealots to express your views publicly then it stands to reason that that same amendment allows the other person to hang with a group of overly liberal gay atheists doing likewise. But more to the point that same amendment dictates that as a society we must allow these two disparate groups to coexist. Majority rule by either extreme has no place at the table. I don't have to like your friends or your ideas and you don't have to like mine. That's why we live in this country. The entire underpinning of freedom rests on the peaceful coexistence of disparate thought.

It's just a matter of time before it's no longer a story when a male athlete declares that he's gay just like it's just a matter of time before no one seriously questions the rights of gays to marry each other. Our disgusting history as a country that has taken too long to right the wrongs borne from discrimination time and time again will eventually catch up with us when it comes to gays and when that finally happens the society and our sports will be the better for it. The economic performance of our country has likewise shown time and again that each time discrimination in some form is eradicated, the economy expands. Why do you think sensible immigration reform is finally getting the serious bi-partisan discussion it deserves?

Fujita was one of several athletes to sign a friend of the court brief in the Supreme Court cases pending over the issue of gay marriage. He supports it. The only question is why everyone else hasn't? Hopefully Fujita and the handful of others like him with a larger pulpit can push the issue even harder.

I'm going to continue to disagree with Fujita on the uneven nature in which he sometimes ham handedly goes about being an advocate for the rights of his fellow athletes but I won't disagree with him on his intentions any longer. He's just a man struggling to stay on the right side of history and sometimes finding that path isn't nearly as elegant as we'd like it to be.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)