Browns Archive

Browns Archive  The Comfort Zone

The Comfort Zone

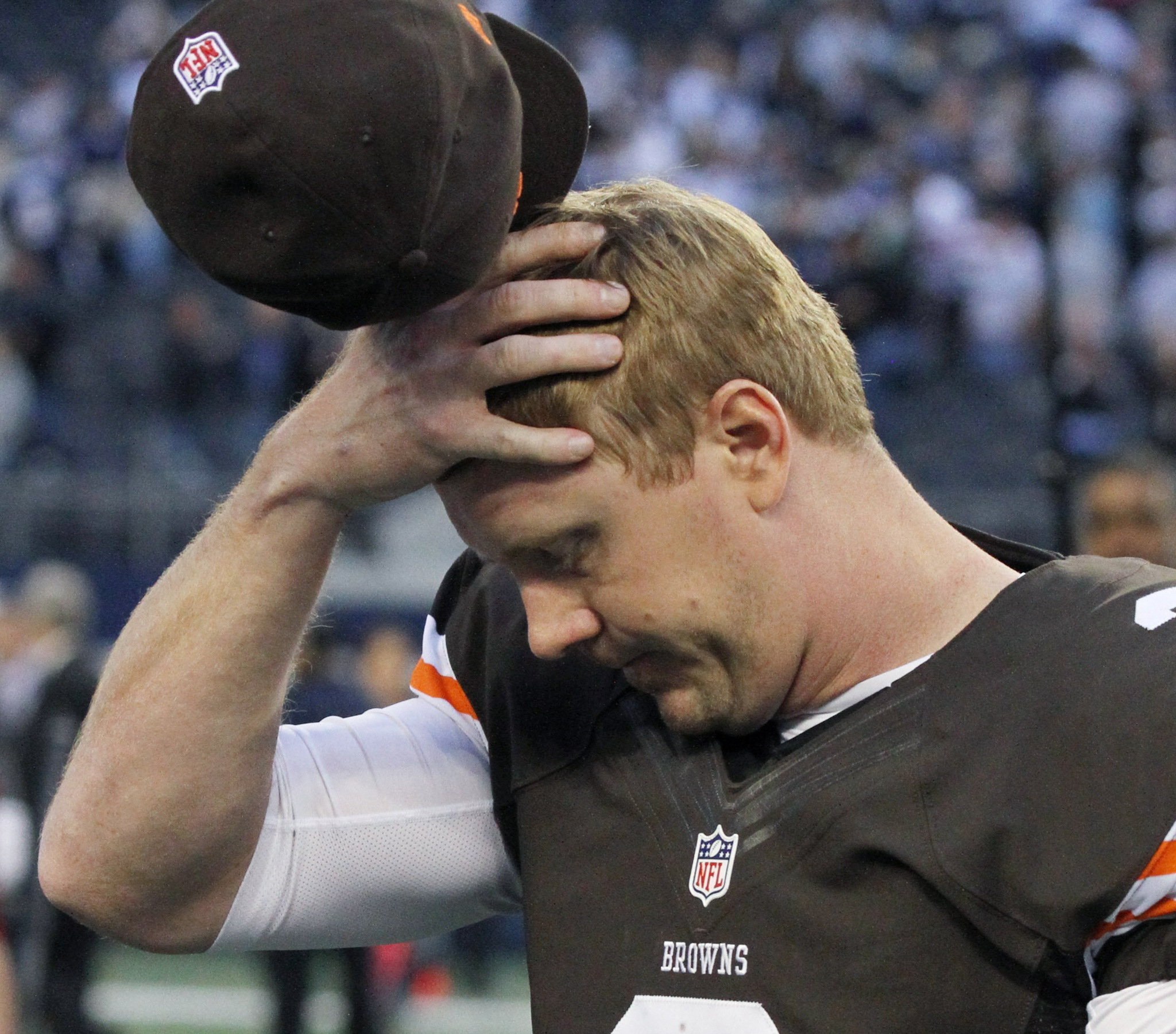

Brandon Weeden left a five-year baseball career behind and returned to football, ostensibly because football is his comfort zone.

Brandon Weeden left a five-year baseball career behind and returned to football, ostensibly because football is his comfort zone.

Though Weeden was a second-round pick of the Yankees in the 2002 MLB Draft, his baseball career never took off. In a second round that included Joey Votto, Jon Lester and Brian McCann, Weeden was one of the comparative duds, never rising above Class A.

He bounced around several different baseball organizations, struggling to climb the minor-league ladder, attempting to master pitches other than a fastball – only to end up as a farmhand in his mid-20s, riding the bus for the A-ball High Desert Mavericks, then an affiliate of the Royals.

The High Desert Mavericks play their home games in Adelanto, Calif., located in San Bernardino County, on the edge of the Mojave Desert. It’s a place where ERAs go to die in the heat and thin air.

Weeden racked up more than 2,800 passing yards in a season – second in the state of Oklahoma – while in high school, so a college football career was always a reliable second option as he toiled away in the minors. By the time he quit baseball after the 2006 season, returning to the place where he had last achieved any real athletic success had to have sounded pretty appealing.

Dodging pass rushers and hitting receivers in stride 30 yards downfield? Piece of cake compared to keeping the ball in the yard at a place that has only slightly more atmospheric pressure than the Moon.

So Weeden enrolled at Oklahoma State in 2007 and made the football team as a walk-on. The adjustment wasn’t easy, but he progressed from redshirt to backup to starter to record-breaking NFL prospect.

He re-wrote the school’s record books as a senior in 2011, setting single-season records in total passing yards, completed passes and completion percentage. In the process, he was named a finalist for the Manning Award – the top quarterback-specific award in college football – and won the Fiesta Bowl in January 2012.

Weeden was most definitely back in his comfort zone. There were probably more than a few moments when he wondered to himself why he wasted half a decade playing minor-league baseball.

Then the Browns made him the 22nd overall pick in the 2012 NFL Draft. And Weeden, who had gone from no-name baseball farmhand to the golden-armed big man on Oklahoma State’s campus, was about to get another serving of humble pie.

Maybe in a parallel universe, Weeden ends up in a more fortunate situation, like Ryan Mallett, another big-armed quarterback who was drafted by the Patriots, and is now being groomed as a possible successor to Tom Brady on one of the league’s most successful teams.

But Weeden ended up in Cleveland, with an organization that has turned losing, instability, turnover, and ruining careers into a way of life over the past 14 years. An organization constantly and desperately searching for saviors upon which to place the crushing burden of eradicating a losing culture, restoring the team to prominence, and ultimately winning the city’s first major pro sports championship in half a century.

Brian Sipe couldn’t do it. Bernie Kosar couldn’t do it. Kenny Lofton, Albert Belle, Jim Thome and Manny Ramirez couldn’t do it. LeBron James didn’t want to do it. And here was Weeden, in the next wave of Marines to storm the beach.

He wasn’t in Oklahoma anymore.

As a 28-going-on-29 rookie, Weeden quickly discovered that football wasn’t his comfort zone. Winning football was his comfort zone. What Weeden had here was a mutant product comprised of the remnants of several failed roster reboots, led by Pat Shurmur, who coached more like a programmed computer, as opposed to a carbon-based life form who could think, feel, react and adjust.

Weeden rebounded from an abysmal debut against the Eagles to have a halfway-decent rookie season. He threw for almost 3,400 yards while completing 57 percent of his passes. He threw 14 touchdowns, but they were outpaced by his interceptions (17). His QB rating was a modest-but-not-humiliating 72.6.

And he did it all while playing in an ultra-conservative offense ultimately aimed at shoehorning him into a Colt McCoy mold. In a setup designed to benefit undersized, scamper-happy QBs who can dodge, dink and dunk, Weeden was a bullwhip-armed, stone-footed, ship’s mast of a QB. He was coached to look underneath first, play the percentages, and take very few risks downfield.

You might as well try to teach a dog to meow. It went against everything in his DNA, both in a metaphorical football sense, and in a very real genetic sense. Big guy, big arm, tiny offense. The fact that Weeden even put up the numbers he did is a minor miracle.

We know what happened from that point. The Browns limped to their fifth straight season of five wins or fewer. New owner Jimmy Haslam bulldozed the front office and coaching staff. Out went Mike Holmgren, Tom Heckert and Shurmur, in came Joe Banner, Mike Lombardi and Rob Chudzinski.

Chudzinski and new offensive coordinator Norv Turner pledged to install an offense that will play more to Weeden’s strengths – a vertical passing attack that embraces the idea of home-run throw and treats the 20-yard out pattern as a staple instead of a seldom-seen change of pace.

But the playbook only matters if Weeden can make it happen on the gridiron. In the NFL, the quarterback is the player who most influences his team’s level of success. A great QB, or QB who gets hot at the right time, can lead his team to great things. Joe Flacco proved it this past winter, as the Ravens won the Super Bowl. An underperforming QB can short-circuit the best-laid plans of coaches, and undermine rock-solid performances by the line, backs and receivers.

Teams with good QBs put the ball in the end zone. Teams with bad QBs don’t. It’s really that simple.

That’s where Weeden is now, as he enters his second year. He appears to have better tools at his disposal, with a pass-friendly offensive scheme, an offensive line anchored by Pro Bowlers and better talent at the receiver position than perhaps at any time since the Browns rebirth.

But the pressure is still there. Weeden still has the expectations of a battered franchise and hopes of a desperate city on his shoulders. And now, he’s no longer a rookie. The kid gloves are off. It’s time for Weeden to render a verdict on himself.

Weeden came back to football because it was always his first love. It was always the place where he felt most capable of success. Or that’s the story. Now we get to really see how comfortable Weeden can be manning football’s most demanding position while attempting one of the most challenging tasks the NFL can offer to a player, coach or executive – turning the Cleveland Browns into a contender.

Hopefully he’s not wishing, at some point, that he was back in Adelanto, watching home runs sail over the fence.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)