Browns Archive

Browns Archive  When You Lose To Win, You Lose

When You Lose To Win, You Lose

In his provocative column from this morning, Joel Witmer suggested that the Browns should lose their last two games. I am certain that he did not mean for them to completely tank these games, but rather to give a level of effort that displays competitiveness while still, um, falling a bit short. (“Gee, Coach, I tried to catch that ball, but it just slipped out of my hands.” “That's OK, Braylon.”) (Then again, how would this exchange be different from any other week?)

Witmer's basic point is that the Browns are going nowhere this season (we can all agree on that one), so the team should broaden its definition of what is “best” for the team to extend to 2007 and seasons beyond. Specifically, that means getting a better slot in next year's NFL Annual Player Selection Meeting.

I do not want to consider any of the other consequences of rooting for the team to “unintentionally intentionally” losing the final two games. I'm not here to talk about the psychological effects of rooting for your favorite team to lose, or the players' capacity to be indifferent when they've spent years being drilled to win, win, win.

Instead, I want to consider one narrow question: does drafting higher, particularly at the top of the draft, improve a team's chances of winning?

Theoretically, that question's an easy one to answer. The player selected with the first pick should be better than the player selected with the second pick, who in turn should be better than the player selected with the third pick, and so it continues until we get to Mr. Irrelevant. Sounds simple, no?

Unfortunately, things are not always as simple as they seem.

The notion that drafting higher leads to a better player is not true for three reasons:

1. Drafting players, particularly is a very inexact science.

This principle is not news to anybody – we all know that a higher draft pick is no guarantee of getting a better player. It increases the chance that you will get a better player, but it's far from money in the bank.

Hey, speaking of money...

2. The higher you draft a player, the more you have to pay him; and the amount increases exponentially for the first several picks.

First-round picks command much more money than players picked in later rounds. Within the first round, the money goes up sharply as you get into the single digits. Hey, the Browns usually draft pretty high ... let's use them as an example:

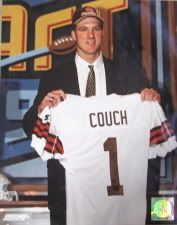

1999: Tim Couch (1st pick overall), $48 million/7 year contract;

2000: Courtney Brown (1), $45 million/7 years;

2001: Gerard Warren (3), $33.6 million/6 years (note: in Gerard's case, that probably did translate into 33.6 million Wendy's Extra Value meals);

2004: Kellen Winslow Jr. (7), $40 million/6 years

2005 Braylon Edwards (3), $40 million/5 years

In contrast, this year's first round pick, Kamerion Wimbley (the 13th overall selection), signed for a relatively paltry $23.7 million over 6 years. And he's arguably been the best of the bunch.

3. The exorbitant amounts paid to top draftees is especially important because of the salary cap.

The salary cap is a zero-sum game. Money that you pay to player A is money that you can't pay to player B. As a result, player B may decide to play elsewhere, leaving you with Player C. The cap can be circumvented to some degree with signing bonuses, roster bonuses, and the like; but eventually, the piper will be paid.

When a team drafts a player high, it is locked into paying a disproportionately large percentage of its cap to that player. (A real problem arises if it is a weak draft, because the compensation packages for top-drafted rookies tends to increase every year. The #1 pick this year will probably get more money than the #1 pick last year, even if last year's #1 is a better player.)

Recent history suggests that as gambling goes, “banking on high draft picks to succeed” falls somewhere between “betting on the roulette wheel” and “hey, let's put the entire nest egg into Enron stock!”. It's easy to point to the Browns' failures in drafting high ... but none of the Browns' high draft picks were shockers. Every one of the players that the Browns selected was ranked high going into the draft. None of the Browns' selections were met by a room of gasps, followed by guffaws; none of them were Jeff Lagemans. Consider the alternatives for each of those seasons:

1999: Instead of Couch, the Browns could have selected Donovan McNabb (picked 2nd) or Edgerrin James (4th) ... but they also could have selected Akili Smith (3rd to the Bengals; now out of football) or Ricky Williams (5th – out of football because NORML is apparently not as effective as he may have hoped).

2000: Courtney Brown's career was hampered by injuries, but look at the alternatives: the me-first LaVar Arrington (2nd), decent-but-unspectacular Chris Samuels (3rd), and mega-bust Peter Warrick (4th).

2001: Neither Michael Vick nor Leonard Davis, who were picked ahead of Warren, have set the world on fire. The classic 20-20 hindsight says that the Browns should have taken LaDainian Tomlinson (who went 5th to San Diego) ... but many others also wanted David Terrell (who went to the Bears at 8).

2004: Winslow has redeemed himself this year, but has he provided better value than, say, the players drafted 10 through 13 (Dunta Robinson, Ben Roethlisberger, Jonathan Vilma, and Lee Evans)?

2005: It is still rather early to judge this draft, but raise your hand if you think that DeMarcus Ware (11th, to Dallas) or Shawne Merriman (12th, to San Diego) have been better than top picks such as Edwards, Alex Smith (1st , to the 49ers), or Ronnie Brown (2nd, to the Dolphins).

Another way to look at the issue is by asking the question: how many top picks have led their teams to the Super Bowl? From 1999-2005, of the 35 players drafted in the first five slots, three (McNabb, Jamal Lewis, and Julius Peppers) have played in a Super Bowl for the team that drafted them. By contrast, in that same period, no fewer than six of the 35 players drafted in slots 11 through 15 helped their teams get to the big game (Damione Lewis, Dan Morgan, Jerome McDougle, Ty Warren, Marcus Trufant, Ben Roethlisberger).

Granted, these facts are tainted by other influences. Teams who draft very high tend to be there because they make bad personnel decisions, and they perpetuate that incompetence by making even more bad picks. Teams in the 11-15 range (the range that I randomly selected for my analysis; I am not pretending that it is a comprehensive study) are often good teams that simply had one bad year.

But the presence of the chicken does not mean that we can ignore the egg. High draft picks tend to not lead their teams to the Promised Land, and they chew up a lot of the salary cap in the process. It sounds crazy to suggest that the Browns would do better drafting, say, 12th than they would drafting 5th. But when you consider the much larger contract that the #5 player will receive ... and the possibility that this contract will become a millstone around the team's neck if the player doesn't produce ... and the distinct possibility that even high picks will turn into disappointments ... it sure doesn't sound as crazy as rooting for your team to lose in order to get that higher pick.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Devone Bess

Spin (Tuesday, January 21 2014 5:35 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 4:38 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 4:07 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 3:42 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM)