Browns Archive

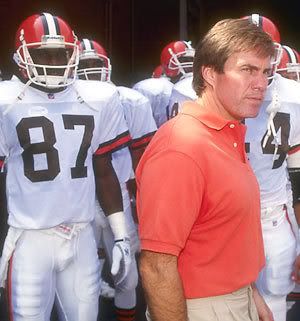

Browns Archive  Bill Belichick's Cleveland Purgatory

Bill Belichick's Cleveland Purgatory

Belichick is a generalisimo, and there are those in Cleveland who think that's too much. They would argue that Belichick's personality is roughly as engaging as that of Francisco Franco... It's safe to assume that group includes the fans who listened to Belichick's postgame interview out on the concourse speakers but continued to chant, "Bill Must Go."

- The Sporting News, December 13, 1993

The roll call of villains in Cleveland sports history is a lengthy one, but during his tenure as head coach of the Browns, Bill Belichick gave away little to anyone else in the city's gallery of rogues. Despite transforming the Browns from one of the worst teams in the league into a legitimate contender within four seasons, the coach's popularity proved the inverse of his team's on-field fortunes. Belichick was widely disliked by his second year, and almost universally despised by his third. A playoff run in 1994 failed to win over the fans, some of whom were heard to grumble that it was kind of a shame the Browns were doing so well, because it meant the coach wouldn't be fired. Shortly after the franchise relocated to Baltimore, the coach was fired, albeit too late for his many Cleveland detractors to derive any enjoyment out of it.

Obviously, Bill Belichick has bounced back. Yet the question remains: how could a football mind so plainly gifted fail so miserably in Cleveland? The superficial analysis says that his regime was doomed from the start by circumstances not of its own making; sucked down in the undertow of the problems that plagued the last years of the original Browns franchise- mere collateral damage from the implosion that rocked the city to its core. And there's a grain of truth to the sentiment. But it's a little bit more complicated than that.

1991

Bill Belichick arrived in Cleveland amidst great fanfare. The youngest coach in the NFL, was also it's hottest assistant, Bill Parcells's right hand (some would say his brain) whose rugged defenses had keyed New York's two Super Bowl titles. He had interviewed for the vacant Browns job two years earlier, but owner Art Modell went with experience over youth and hired Bud Carson instead. In the meantime, while Belichick won another Super Bowl as the Giants' defensive coordinator, Cleveland crumbled. In 1990 the Browns lost a franchise-record thirteen games and gave up the most points in the league- 462, nearly twenty-nine per game. They lost nine games by double-digit margins. The Cleveland Plain Dealer called 1990 "the Season from Hell". That might have been an understatement.

Belichick's task was daunting. The window had slammed shut on the teams that made three AFC title-game appearances in the late ‘80s. Holes yawned throughout an aging, cadaverous roster. Franchise quarterback Bernie Kosar had taken a beating behind the horrendous offensive line, the running backs as a group were among the worst in the league, the linebacker corps was years past its collective prime and the secondary, one of the NFL's best in the previous decade, had to be massively overhauled. The team was a handyman's special.

Not surprisingly, in his first draft the defensive guru went heavily for defensive help. With the second overall pick, the Browns took Eric Turner, a big, physical safety from UCLA, and in total the team used six of its eleven selections on defensive players, including four defensive tackles. Cleveland spent its second-round pick on a guard, Ed King of Auburn, and its sixth-rounder on wide receiver Michael Jackson, Brett Favre's favorite target at Southern Mississippi. It was a decent, albeit unspectacular draft; unfortunately, it would prove the best of Belichick's tenure.

The new coach's debute on September 1, 1991 at Municipal Stadium, was inauspicious- a 26-14 loss to the fast-rising Dallas Cowboys. But despite the opening hiccup, Browns had every reason to be optimistic as Belichick's reign began. The new coach broke into the win column in the season's second week, with a 20-0 victory over New England at Foxboro, then rookie kicker Matt Stover nailed a field goal with no time left to beat the Bengals 14-13 at the Stadium. Three straight losses- including a 13-10 defeat to Belichick's old Giants comrades- followed, then Cleveland broke the skein with an overtime victory in San Diego and evened its record at 4-4 by edging Chuck Noll's last Steelers team, 17-14. Midway through the season the Browns had already surpassed their victory total from 1990. Things went downhill from there.

At Riverfront against the winless Bengals in Week Nine, the Browns got out to a quick 14-3 lead, fell victim to a Cincinnati comeback, and lost 23-21 after they botched two field goal attempts in the final moments. The following week the Browns took a 23-0 lead over the Eagles but fell apart and lost 32-30. They made it three losses in a row when they blew a 17-7 lead in the Astrodome in a Sunday Night contest and lost to the Oilers in the last seconds, 28-24. This pattern of potential wins turned into heartbreaking losses was to persist throughout Belichick's tenure, and it would prove a flashpoint for dissatisfaction with the coach among the public.

The Browns rallied for consecutive victories over Kansas City and Indianapolis, than lost their last three to finish with a 6-10 record. Despite the disappointing finish there was reason to be pleased with the team's performance. The defense improved dramatically, giving up 164 fewer points than in 1990. Bernie Kosar had his best season in several years, throwing for 3,487 yards and eighteen touchdowns with a solid 87.8 rating. Leroy Hoard, a second-round pick in 1990, caught nine touchdown passes from his halfback position. Rookies Eric Turner, Ed King, James Jones and Michael Jackson got significant playing time and showed promise. And in a welcome change from the Blowout City that was 1990, the Browns played close, competitive football almost every week. The team's only lopsided defeat came in RFK Stadium to the World Champion Redskins, and even that was a 21-17 game in the fourth quarter, before Washington scored three unanswered touchdowns to stretch the final margin to 42-17. The Browns still lost more than they won, but they generally made things interesting, and even that represented significant progress.

Belichick was not unpopular with the Cleveland fans in his first year. No one doubted his skills with X's and O's and for the most part, people were inclined to credit him for squeezing blood out of the turnip that was the team's roster. Matters were different with the media, however. Clad in a jarringly casual rubber workout shirt, Belichick was alternately terse and sarcastic in his press conferences, and his practices were closed. The press climbed on his back from the get-go and never got off. Belichick, of course, could care less.

Stay tuned over the next week to read the remaining installments of this fantastic piece by Jesse:

~1992

~1993

~1994

~1995 and epilogue

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)