Browns Archive

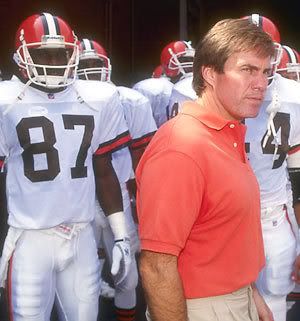

Browns Archive  Bill Belichick's Cleveland Purgatory

Bill Belichick's Cleveland Purgatory

Belichick is a generalisimo, and there are those in Cleveland who think that's too much. They would argue that Belichick's personality is roughly as engaging as that of Francisco Franco... It's safe to assume that group includes the fans who listened to Belichick's postgame interview out on the concourse speakers but continued to chant, "Bill Must Go."

- The Sporting News, December 13, 1993

The roll call of villains in Cleveland sports history is a lengthy one, but during his tenure as head coach of the Browns, Bill Belichick gave away little to anyone else in the city's gallery of rogues. Despite transforming the Browns from one of the worst teams in the league into a legitimate contender within four seasons, the coach's popularity proved the inverse of his team's on-field fortunes. Belichick was widely disliked by his second year, and almost universally despised by his third. A playoff run in 1994 failed to win over the fans, some of whom were heard to grumble that it was kind of a shame the Browns were doing so well, because it meant the coach wouldn't be fired. Shortly after the franchise relocated to Baltimore, the coach was fired, albeit too late for his many Cleveland detractors to derive any enjoyment out of it.

Obviously, Bill Belichick has bounced back. Yet the question remains: how could a football mind so plainly gifted fail so miserably in Cleveland? The superficial analysis says that his regime was doomed from the start by circumstances not of its own making; sucked down in the undertow of the problems that plagued the last years of the original Browns franchise- mere collateral damage from the implosion that rocked the city to its core. And there's a grain of truth to the sentiment. But it's a little bit more complicated than that.

Part I - The 1991 season

Part III - The 1993 & 1994 seasons

1995

It was another tumultuous off-season. Two more impact players who had preceded Belichick in Cleveland were shown the door- Eric Metcalf and defensive tackle Michael Dean Perry, both of whom had gone to the Pro Bowl in 1994. Metcalf went to Atlanta, where he was moved to wide receiver and caught 104 passes for 1,189 yards in 1995. Perry moved to Denver, where he started for a Broncos team rounding into Super Bowl contention.

And it was another draft day that seemed design to exasperate. Belichick traded up to grab the tenth pick in the first round, with which he planned to take Penn State tight end Kyle Brady. When the Jets grabbed Brady with the ninth pick, the coach suddenly felt a keen lack of a Plan B. In what looked to everyone like a panic move, Belichick shuffled the tenth selection to the 49ers for their first-round pick- the thirtieth and last- and San Francisco's first-rounder in 1996. Belichick used the pick to select Ohio State linebacker Craig Powell, who wasn't even the best player on his own unit in college and who never made an impact for the Browns or anyone else. Belichick's draft-day machinations were lampooned by fans and media alike at the time. A year later, the Baltimore Ravens, using that extra first-round pick secured the previous year by a different franchise in a different city, selected linebacker Ray Lewis of Miami (Fl.).

It's important to remember that, right up until the November day the move to Baltimore was announced, the vast majority of Browns fans knew nothing about the real state of the franchise. They had no idea that Art Modell had been forced to borrow the money for the signing bonus given to free-agent receiver Andre Rison. They were unaware that Modell was irate at the sight of the Indians winning a pennant in the plush comfort of brand-new Jacobs Field- and impoverished without the income the Tribe had provided in rent to Modell’s Stadium Corporation. They didn’t know that Modell had been negotiating with the city of Baltimore. All of these things came to light in the wake of the announcement. But for the first eight weeks of the season, it was just another fall of Browns football- albeit with the toxic Belichick included.

After an opening loss to the Patriots, the Browns won three straight. They dropped to 3-2 following a 22-19 Monday Night loss at home to the Bills. A bad loss at Detroit and a shocking home defeat to the expansion Jacksonville Jaguars followed, dropping the Browns below .500 at 3-4. They evened their record with a win in Cincinnati. Then came the announcement of the move on November 6, 1995- and the season promptly fell apart. The Browns went into a painful, boneless slide to a 1-7 finish. The 5-11 record was a neat reversal of the previous season's mark.

Certainly the move was out of Bill Belichick’s hands. So, as it turned out, was the signing of Andre Rison, who made just 47 catches and spent more time making vulgar remarks about Browns fans as he did making plays on the field. Rison's attitude and lack of production further alienated a fan base that wasn't exactly hunting for reasons to run away from their team. Not all- not many, even- of the club's woes in 1995 can be traced to Belichick. Nevertheless, he was there, and all of the tumult and acrimoniousness that had characterized his tenure came to a head over the eight-week nightmare that followed the announcement. Fair or not, a great deal of the vitriole that had built up over the move now came down on Belichick. And all the while, Belichick was Belichick. His quarterback games continued, as he benched Testaverde for Eric Zeier midway through the season in a move that brought nothing but more losses. In another bizarre move, he called timeout in the final seconds of a game at San Diego and ordering Matt Stover to kick a field goal- while the Browns were behind by three touchdowns.

The end for Belichick came soon after the team relocated to Baltimore. Art Modell dispatched his coach with a phone call, in the same bloodless fashion in which Bill had gotten rid of so many of Cleveland’s favorites. Modell had once declared that Belichick “is the last coach I’ll hire.” Then again, he probably said that about every coach.

EPILOGUE

From the first game of his first season as coach, Bill Belichick had the Browns playing competitively if not successfully, and as the years went on, he molded them into a unit contemporary Patriots fans might recognize- stingy on defense, excellent on special teams, and relatively mistake-free. The early ‘90s Browns were a hothouse of up-and-coming coaching and front-office talent- Nick Saban, Kirk Ferentz, Pat Hill, Eric Mangini, Scott Pioli, Ozzie Newsome, and Phil Savage all cut their teeth working with Belichick in Cleveland. On several occasions- at Dallas in 1994, at home against the Steve Young-Jerry Rice 49ers in 1993, at the Astrodome against the Oilers in ’92- the Browns won impressively over teams with blatantly superior talent through superior coaching, discipline, and execution.

So all this aside, why did the man fare so miserably in Cleveland? There are a lot of reasons. Some involved factors far beyond Bill Belichick’s control.

It was beyond Belichick's control, certainly, that he was coaching under an owner that was flat-busted broke, and in a stadium that was, to put it nicely, dilapidated. The stadium situation in New England is approximately one thousand times better than it was in Cleveland. Gillette Stadium is brand-new and state-of-the-art, and although the coach’s first two Patriot seasons were played in 30-year old Foxboro Stadium, that park was never as run-down as Municipal Stadium even on its worst day.

And comparing Robert Kraft to Art Modell as owners is like comparing Abraham Lincoln with Chester Allen Arthur as statesmen. Kraft has never, and will never, foist a player like Andre Rison on his coach. Kraft, unlike Modell, is independently wealthy. Art Modell didn't make a fortune in the paper industry. He didn't own scads of real estate around the globe. Art Modell was the owner of the Cleveland Browns- period. Which meant two things; he never had the scratch other owners had, and since the Browns were the sum of his existence, he was a compulsive meddler in the team's on-the-field affairs, generally with disastrous results.

But although the state of the franchise was quite grave throughout Belichick's tenure, let's not let him all the way off the hook.

Belichick had no true offensive coordinator until 1994 (and even that year, the OC was a syncophant- running backs coach Steve Crosby). In Belichick's first three years in Cleveland, he ran the offense. Even then he occasionally displayed the now-familiar flair for the unexpected- for example, his '94 Browns are the first team to execute a two-point conversion in an NFL game. But his personnel decisions on offense were volcanic. His notable 'cuts' were on offense- Bernie Kosar, Reggie Langhorne, etc. His most controversial coaching maneuvers primarily affected the offense- and it was the offense that provided the heaviest anchor on the club's fortunes, finishing no higher than 18th in total yardage during Belichick’s five-year reign.

Whether it was the by-product of this terminal mediocrity or its cause, the quarterback position was in a state of near-constant flux. Shifting uncomfortably from one “guy” to the next, Belichick- in the throes of personality conflicts and misguided fits of inspiration- benched his starter while his team was winning and cut his starter while his team was in first place and his backup was on the injured list. It was unorthodox, it was daring, and it was disastrous. As solid as they were in several phases, the early-90s Browns were limited by their architect’s ham-fisted dealings with his quarterbacks.

One wonders how Belichick’s Browns would have fared with Tom Brady. One also wonders how his Patriots would have fared without Tom Brady.

The team’s draft record during Belichick’s tenure, although not as famously bad as that of the expansion Browns in 1999 and 2000, left a great deal to be desired. Of the forty-one players taken in the five drafts of the Belichick era, only one- Eric Turner- ever made it to a Pro Bowl. It’s a matter of talent, and the Browns of the early ‘90s were mediocre largely because they had mediocre talent.

Not gregarious like Sam Rutigliano, nor stoutly confidence-inspiring like Marty Schottenheimer, Belichick also wasn't capable of coming out and explaining the decisions he made- the good ones or the bad- in a way that reassured or even adequately informed fans and the media. Belichick has admitted that while he was in Cleveland he attempted to emulate the acerbic Bill Parcells in dealing with the press. In his dry way, Bill called this a “miscalculation”. Was it ever. Even at his most contemptuous and belittling, Parcells was, at bottom, playing a part, and the hard-edged East Coast press gobbled it up. When Belichick tried the caustic tack with the Cleveland media- without the wins, or reputation of his coaching sinsei- he simply came off as an asshole from New York. Some of the regard in which the local press held him is captured in a column written by the Akron Beacon-Journal’s Terry Pluto just after Modell fired Belichick in early 1996:

He believed that we Midwestern hayseeds knew nothing about football. We were supposed to believe that this man who never played at a higher level than NCAA Division III – Wesleyan actually – a man who was a better lacrosse than football player... a man who never had been a head coach anywhere at any time before...We were supposed to believe this man invented the game.

Pluto goes on to describe Belichick as "gutless and rude... pure arrogance... a man who (had turned) the fans against the team they loved." One can imagine how the other writers felt.

But as it turned out, Belichick, whose father Steve hailed from the Youngstown area, had a pretty good idea of what Midwesterners knew of football. During the 2003 season, just before New England hosted the Browns, he stated it:

"They have enthusiastic fans. They are knowledgeable fans. That is the cradle of football; that is where it started. That is where the Hall of Fame is. High school football is big. There are, I don't know how many colleges in Ohio play football. It must be 40 or 50, whatever it is. There is a lot of football there and there are a lot of fans. The people know the game and they know it well. They are knowledgeable and they are passionate for it."

Browns fans are sentimentalists. They have to be, really. And they have never been more sentimental than when it came to the teams of the 1980’s, the ones repeatedly martyred by John Elway. Belichick saw the veteran remnant of those teams as an over-the-hill obstacle to his plans for rebuilding the team. As quoted in Tony Grossi's Tales From The Cleveland Browns Sideline:

"There were a lot of great Cleveland players when I got there who were at the end of their careers... whether I released them and they never played again, or they played marginally for a year or two afterwards, there was a long list of them."

Belichick, in his rather self-serving account, ignored the fact that Reggie Langhorne and Webster Slaughter each had two very good seasons after leaving Cleveland. But he was essentially correct. At a distance of a decade-and-a-half, a lot of the personnel moves made by Belichick involving the old Schottenheimer-era Browns made good sense. Most of these players really didn't have much left in the tank. But their handling was ham-fisted. Belichick sold key veterans in New England on what he wanted to do and how he wanted it done. He was a failure at the same game in Cleveland, and as a result he felt compelled to purge the roster of a lot of very popular players.

As buffeted as it was by the winds of public opinion, Belichick’s ship-of-state would have found smooth seas had the coach simply won more games. He didn’t. Even not factoring the abortion that was the ’95 season, Belichick was an uninspiring 31-33, making the playoffs just once in the first four years of his regime, and not at all in the first three. There wasn’t enough on-field success when the extra baggage was factored in. Had Bill Belichick won a Super Bowl in Cleveland, the release of Bernie Kosar would have been a detail of history, not a crucible.

Winning cures everything. Losing makes a genius into a bum. Bill Belichick didn’t win in Cleveland. Who’s at fault? Well…

At the end of all this, there’s the stark fact of the Move, the great destroyer, the wrecker of the continuum of the Cleveland franchise. The Move stopped the clock. It rendered all judgments null and void. There is no answer to the question of what transpires in Cleveland through an un-ravished 1995 and then on into the end of the decade. Belichick’s career was ill, but it died in an unrelated disaster, and we have no idea whether or not time and circumstance would have healed it. We’re left with reasons for nothing and conclusions to nothing- nothing but a Cleveland purgatory.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)