Browns  Browns Archive

Browns Archive  A Trail Of Tears

A Trail Of Tears

Browns Archive

Browns Archive  A Trail Of Tears

A Trail Of Tears

Written by

Erik Cassano

When a city loses a pro sports team, the ripple effects can last for years. Few cities took it on the chin harder than New York, which lost both its National League teams in the same offseason prior to 1958. It happened to us here in Cleveland when Art Modell snuck the Browns out the back door in 1995. And now it has happened in Seattle, who will lose their Supersonics to Oklahoma City. Erik Cassano talks about the history and current state of franchise relocation in his latest for us.

When a city loses a pro sports team, the ripple effects can last for years. Few cities took it on the chin harder than New York, which lost both its National League teams in the same offseason prior to 1958. It happened to us here in Cleveland when Art Modell snuck the Browns out the back door in 1995. And now it has happened in Seattle, who will lose their Supersonics to Oklahoma City. Erik Cassano talks about the history and current state of franchise relocation in his latest for us.

Legendary Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey once said that a baseball team in any city is quasi-public institution, but the Dodgers were public without the quasi.

Legendary Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey once said that a baseball team in any city is quasi-public institution, but the Dodgers were public without the quasi.

When a city loses a public institution, the ripple effects can last for years. Few cities took it on the chin harder than New York, which lost both its National League teams in the same offseason prior to 1958. The Dodgers and Giants, both staples of New York summers dating to the 19th Century, packed up and moved to the West Coast.

After 1957, Ebbets Field never saw big league baseball again. It was knocked down a few years later. The Polo Grouds, the Giants' oddly-shaped landmark of a park in extreme northern Manhattan, remained vacant until the Mets moved in for the 1962 season. By 1964, however, the Mets had moved to Shea Stadium and the Polo Grounds followed Ebbets Field into the crosshairs of the wrecking ball.

The sports history books are loaded with teams leaving various locales and arriving in others. Baseball, in particular, went through a glut of relocation over approximately 20 years. In addition to the Dodgers and Giants, the Braves left Boston in 1953 for Milwaukee, then moved south to Atlanta in 1966. The Athletics left Philadelphia for Kansas City in 1954, then moved westward yet again to Oakland in 1968.

The St. Louis Browns became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954. The Washington Senators became the Minnesota Twins in 1961, replaced a year later with an expansion Washington Senators franchise, which became the Texas Rangers in 1972. The Seattle Pilots left the Pacific Northwest after one unremarkable expansion season, becoming the Milwaukee Brewers in 1970.

It makes for good reading if you are into sports history and like to memorize random facts. But the impact felt by the fans losing their team is hard to appreciate until it happens to one of your teams.

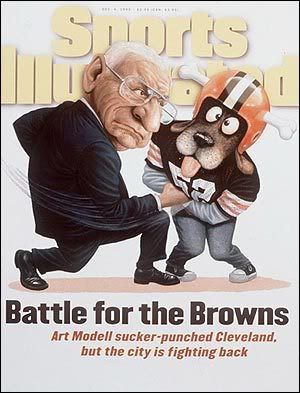

In 1995, we felt it in Cleveland. Most people still remember where they were when Art Modell stood on that stage in Baltimore and announced to a throng of enthusiastic fans and city leaders that he was filling the pro football hole in their hearts by creating one in ours. What followed was an ugly several-year sequence involving the NFL, the governments of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County and tens of thousands of irate fans who will see to it that Arthur B. Modell is unwelcome in Cleveland, Ohio for the remainder of his natural life.

We retained the Browns name and history. We also received a hastily-constructed stadium and expansion team for our trouble, a team virtually guaranteed to not contend for at least five years. Nearly 10 years and two regime changes later, we are only now starting to see evidence of a well-run, winning Browns organization begin to sprout.

Meanwhile, Modell hoisted high the Vince Lombardi Trophy in January 2001. He handed the Baltimore Ravens off to new ownership in 2004, having won the Super Bowl title we still covet.

Ever since the dominoes of despair started falling on that Autumn day in 1995, I've been sensitive to the plight of fans losing their teams, particularly if the fans have supported the team for decades through thick and thin.

Even when the Expos' situation in Montreal was well beyond repair, I thought about the loyal Expos fans, though small in number by the team's 2004 end, who were losing a small part of themselves so the franchise could move on to greener pastures in Washington, D.C. -- which was getting a nearly unheard-of third chance as a baseball town.

You simply don't lose a franchise after 35 years without twisting a knife in someone's back -- thousands of times over. Which is why, when the latest franchise to pogo-stick out of a city made their move official last week, I once again felt that same special brand of contempt that I felt when the Browns moved. That certain type of contempt that can only be reserved for incredibly rich businessmen and politicians who treat the sports team into which you invested so much of your heart and paychecks over the years like a bargaining chip.

The story of the Sonics' exodus to Oklahoma City is, like so many other franchise moves, the story of powerful men attempting to throw each other under the proverbial bus. It's the story of a relationship that had become so contentious between Seattle leaders and team owner Clay Bennett that the sides negotiated a settlement that would allow the Sonics to leave town ahead of the 2010 expiration of the team's lease with the supposedly-outdated Key Arena, just so the sides wouldn't have to deal with each other anymore.

It's the story of former owner Howard Schultz selling his team to Bennett, an Oklahoma businessman, then suing Bennett for control of the team because, of course, Schultz wants to stand up for Seattle in the face of this Oklahoma carpetbagger. It's a move that now seems like a shallow attempt by Schultz -- whose tenure as the Sonics' owner is not remembered fondly by most in Seattle -- to save face with the thousands of now-former Sonics fans who drink his notoriously-overpriced Starbucks coffee.

It's the story of Seattle government refusing to buckle to pressure and finance the building of a new arena, and paying the price for doing what is right --though the city might end up with an extra $75 million out of this whole fiasco as part of the settlement with Bennett and his investors. But if Seattle wants NBA basketball back, it will likely have to spend that amount several times over to build a new arena, sooner or later.

It's the story of legal wrangling and finger-pointing and a lot of hot air. But most of all, it's the story of 41 years of basketball, about Dennis Johnson and Jack Sikma and Lenny Wilkens and the only pro sports title in Seattle's modern history, claimed in 1979.

It's the story Gary Payton's slick handle at the point guard spot, of the pre-Cleveland Shawn Kemp, one of the most astonishing athletic specimens the game had ever seen. It's the story of Nate McMillan, Sam Perkins and all the other players who made a mark on Seattle in four decades of pro basketball.

That is what the fans lost. The ability to make more memories, the ability to watch the latest Sonics phenom, Kevin Durant, blossom into a superstar.

The years will pass, Seattle might land a replacement for the Sonics -- and it might even carry the Sonics name. But it won't be the same, even if they fall in love again.

We in Cleveland, who remember those bitter Sundays on the lakefront in the spartan confines of Cleveland Stadium, turning it into a disorienting vortex of noise for anyone wearing the opposing team's colors, can attest to that.

Life goes on, but you can't ever really, truly go home again.

Legendary Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey once said that a baseball team in any city is quasi-public institution, but the Dodgers were public without the quasi.

Legendary Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey once said that a baseball team in any city is quasi-public institution, but the Dodgers were public without the quasi.When a city loses a public institution, the ripple effects can last for years. Few cities took it on the chin harder than New York, which lost both its National League teams in the same offseason prior to 1958. The Dodgers and Giants, both staples of New York summers dating to the 19th Century, packed up and moved to the West Coast.

After 1957, Ebbets Field never saw big league baseball again. It was knocked down a few years later. The Polo Grouds, the Giants' oddly-shaped landmark of a park in extreme northern Manhattan, remained vacant until the Mets moved in for the 1962 season. By 1964, however, the Mets had moved to Shea Stadium and the Polo Grounds followed Ebbets Field into the crosshairs of the wrecking ball.

The sports history books are loaded with teams leaving various locales and arriving in others. Baseball, in particular, went through a glut of relocation over approximately 20 years. In addition to the Dodgers and Giants, the Braves left Boston in 1953 for Milwaukee, then moved south to Atlanta in 1966. The Athletics left Philadelphia for Kansas City in 1954, then moved westward yet again to Oakland in 1968.

The St. Louis Browns became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954. The Washington Senators became the Minnesota Twins in 1961, replaced a year later with an expansion Washington Senators franchise, which became the Texas Rangers in 1972. The Seattle Pilots left the Pacific Northwest after one unremarkable expansion season, becoming the Milwaukee Brewers in 1970.

It makes for good reading if you are into sports history and like to memorize random facts. But the impact felt by the fans losing their team is hard to appreciate until it happens to one of your teams.

In 1995, we felt it in Cleveland. Most people still remember where they were when Art Modell stood on that stage in Baltimore and announced to a throng of enthusiastic fans and city leaders that he was filling the pro football hole in their hearts by creating one in ours. What followed was an ugly several-year sequence involving the NFL, the governments of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County and tens of thousands of irate fans who will see to it that Arthur B. Modell is unwelcome in Cleveland, Ohio for the remainder of his natural life.

We retained the Browns name and history. We also received a hastily-constructed stadium and expansion team for our trouble, a team virtually guaranteed to not contend for at least five years. Nearly 10 years and two regime changes later, we are only now starting to see evidence of a well-run, winning Browns organization begin to sprout.

Meanwhile, Modell hoisted high the Vince Lombardi Trophy in January 2001. He handed the Baltimore Ravens off to new ownership in 2004, having won the Super Bowl title we still covet.

Ever since the dominoes of despair started falling on that Autumn day in 1995, I've been sensitive to the plight of fans losing their teams, particularly if the fans have supported the team for decades through thick and thin.

Even when the Expos' situation in Montreal was well beyond repair, I thought about the loyal Expos fans, though small in number by the team's 2004 end, who were losing a small part of themselves so the franchise could move on to greener pastures in Washington, D.C. -- which was getting a nearly unheard-of third chance as a baseball town.

You simply don't lose a franchise after 35 years without twisting a knife in someone's back -- thousands of times over. Which is why, when the latest franchise to pogo-stick out of a city made their move official last week, I once again felt that same special brand of contempt that I felt when the Browns moved. That certain type of contempt that can only be reserved for incredibly rich businessmen and politicians who treat the sports team into which you invested so much of your heart and paychecks over the years like a bargaining chip.

The story of the Sonics' exodus to Oklahoma City is, like so many other franchise moves, the story of powerful men attempting to throw each other under the proverbial bus. It's the story of a relationship that had become so contentious between Seattle leaders and team owner Clay Bennett that the sides negotiated a settlement that would allow the Sonics to leave town ahead of the 2010 expiration of the team's lease with the supposedly-outdated Key Arena, just so the sides wouldn't have to deal with each other anymore.

It's the story of former owner Howard Schultz selling his team to Bennett, an Oklahoma businessman, then suing Bennett for control of the team because, of course, Schultz wants to stand up for Seattle in the face of this Oklahoma carpetbagger. It's a move that now seems like a shallow attempt by Schultz -- whose tenure as the Sonics' owner is not remembered fondly by most in Seattle -- to save face with the thousands of now-former Sonics fans who drink his notoriously-overpriced Starbucks coffee.

It's the story of Seattle government refusing to buckle to pressure and finance the building of a new arena, and paying the price for doing what is right --though the city might end up with an extra $75 million out of this whole fiasco as part of the settlement with Bennett and his investors. But if Seattle wants NBA basketball back, it will likely have to spend that amount several times over to build a new arena, sooner or later.

It's the story of legal wrangling and finger-pointing and a lot of hot air. But most of all, it's the story of 41 years of basketball, about Dennis Johnson and Jack Sikma and Lenny Wilkens and the only pro sports title in Seattle's modern history, claimed in 1979.

It's the story Gary Payton's slick handle at the point guard spot, of the pre-Cleveland Shawn Kemp, one of the most astonishing athletic specimens the game had ever seen. It's the story of Nate McMillan, Sam Perkins and all the other players who made a mark on Seattle in four decades of pro basketball.

That is what the fans lost. The ability to make more memories, the ability to watch the latest Sonics phenom, Kevin Durant, blossom into a superstar.

The years will pass, Seattle might land a replacement for the Sonics -- and it might even carry the Sonics name. But it won't be the same, even if they fall in love again.

We in Cleveland, who remember those bitter Sundays on the lakefront in the spartan confines of Cleveland Stadium, turning it into a disorienting vortex of noise for anyone wearing the opposing team's colors, can attest to that.

Life goes on, but you can't ever really, truly go home again.

Posted by

Erik Cassano

Jul 07, 2008 7:00 PM

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)