Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Blast From The Past: Eric Turner (and a love letter to Cleveland Municipal Stadium)

Blast From The Past: Eric Turner (and a love letter to Cleveland Municipal Stadium)

The approaching Stadium lights shimmered near the horizon. They lent a dynamic of excitement matching that which my father and I shared. The Browns weren’t having a good season. And today, they were facing the Cincinnati Bengals, a bad team which had already beaten the Browns weeks earlier. But this was Game Day. The lights of the Stadium were our beacon, signaling against the dark sky near the choppy waters of Lake Erie.

The approaching Stadium lights shimmered near the horizon. They lent a dynamic of excitement matching that which my father and I shared. The Browns weren’t having a good season. And today, they were facing the Cincinnati Bengals, a bad team which had already beaten the Browns weeks earlier. But this was Game Day. The lights of the Stadium were our beacon, signaling against the dark sky near the choppy waters of Lake Erie.

Pretty dramatic. If you’re a Browns fan, you understand.

Before we reached the Stadium, we pulled off the Shoreway and parked in the long, narrow Municipal lot. Since we had arrived early, there was no need to hurry. Small groups of bundled-up fans dotted the lot, some tossing around footballs. To the left, lining the southern edge of the lot, a line of train cars stood idle on its tracks. As we proceeded toward the Stadium, we passed by a bridge abutment. On the concrete was one piece of graffiti: the words “Steelers Suck” in small, permanent, black letters.

My awesome wife had gifted me tickets to three games that season. This was Dad’s turn to share in my pilgrimage.

We bore right, under another bridge and up a short slope. We now stood at the foot of the huge, dingy, yellow monolith. Gate D; beneath the thirty-foot tall Chief Wahoo sign attached at the roof. Scores of fans were shifting in various directions. Some simply mingled about; others pushed on to other gates, or had just arrived from the cindered stadium lot to the right.

Our pace was slowed by the crowd. We nudged through one of the blue jeans-polished, rotating turnstiles and found ourselves inside. I reveled in the familiar dank air as we walked amidst the damp concrete. Fresh cigars and stale beer. I was reminded that even the outer concourse on the ground floor of the Stadium was huge. We walked up the nearest incline to the upper levels, glancing at the peeling paint and the random small broken stadium-wall window pane (which was unreachable from the ramp, let alone repairable). Faraway sounds reverberated among the nearby noises. “Beer here!”

Arriving at the upper deck, we duly paid respects to the nearest galvanized steel urinal troughs (and noted some sinks and a trash can which certainly would later share their fate). We purchased our first cellophane-covered paper cups of beer and sank into our seats. The Browns were on the field, stretching and casually warming up. Doc Severinsen’s trumpet echoed live over the P.A. Far below, the field was animated, a stage under the spotlights. Dad pointed down to the closest end zone, where last year’s top draft pick jogged past this year’s.

“Eric Turner and Tommy Vardell. They may not figure much into this game, but for the Browns to be any good, they’ll both need to become star players.”

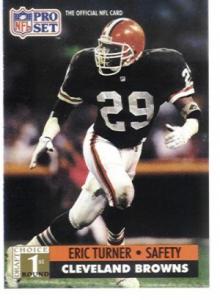

Known as “E-Rock” from his All-American days at UCLA, Eric Turner was a fierce hitter, an enforcer in the vaunted Cleveland secondary (he followed in former Bruins great Don Rogers’ footsteps as a Browns safety). The NFL had not yet fostered the softer brand of defense it would legislate years later; for instance, hits on a quarterback were not yet limited to the region between the shoulders and the thighs. And separating a receiver from a football was a legitimate goal. Often, it was the whole point. In Turner’s rookie season of 1991, he delivered two vicious blows to Houston Oilers receivers. He knocked out Ernest Givens on one such collision. Turner was also strong in run support. This was illustrated on his first NFL tackle, in which he bent the facemask of Bengals running back James Brooks.

Known as “E-Rock” from his All-American days at UCLA, Eric Turner was a fierce hitter, an enforcer in the vaunted Cleveland secondary (he followed in former Bruins great Don Rogers’ footsteps as a Browns safety). The NFL had not yet fostered the softer brand of defense it would legislate years later; for instance, hits on a quarterback were not yet limited to the region between the shoulders and the thighs. And separating a receiver from a football was a legitimate goal. Often, it was the whole point. In Turner’s rookie season of 1991, he delivered two vicious blows to Houston Oilers receivers. He knocked out Ernest Givens on one such collision. Turner was also strong in run support. This was illustrated on his first NFL tackle, in which he bent the facemask of Bengals running back James Brooks.

The Browns made “ET” the highest NFL draft pick for a defensive back in almost thirty years (he was 2nd overall in 1991). They also made him the highest-paid NFL rookie to date. He suffered a stress fracture in his leg that year, but was poised to challenge the likes of Ronnie Lott in bringing the intimidation factor among defensive backs in 1992. This was the season in which he and fellow safety Stevon Moore began their practice of delivering crushing blows to running backs early in training camp, as a way to set the tone for the new season.

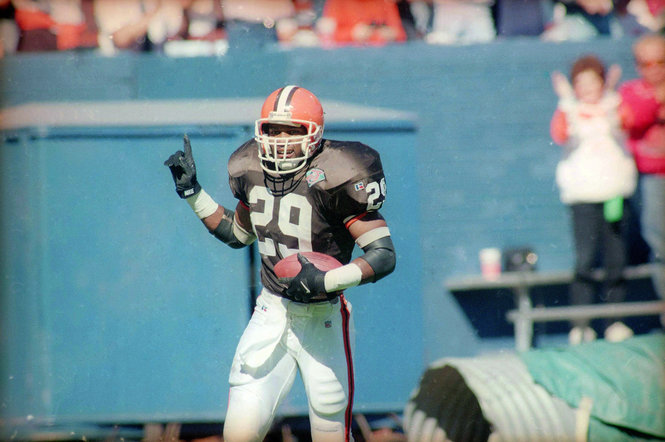

Number 29 moved with a confidence, a purpose. Dad and I leaned forward, and then to the side to get an clear view around the steel pillar which stood several rows in front of us. Meanwhile, the jealous Stadium wind occasionally imposed itself completely through our layers of winter parkas, lucky t-shirts and sweaters, and long underwear.

Eric Turner had an external off-field persona which shouted “Hollywood”- from his wardrobe, to his sunglasses, to his designer watch (set to California time). However, he also was known as having such character and firm Christian resolve that befitted the “rock” moniker. He enjoyed the study of history in college, and entertained a future career in the field of law.

As I’d always preferred to do, we eventually experienced the football game from various points around the Stadium. We settled onto a path on the outer concourse below our seats. From there, we could constantly watch along the line of scrimmage. The main obstruction were the loges hanging from the upper deck, which shielded forward passes, punts and kickoffs from our view. We gladly accepted this as a tradeoff for strained glimpses at muted replays on the television monitors, which were mounted on the open-air hallways at the rear of the loges. Besides, it was warmer, and easier to share thoughts with the two- and three-deep smattering of kindred Browns fans.

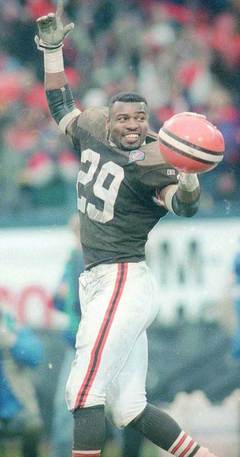

Turner’s all-around game was improving to the point that, by 1994, he would make 1st team All-NFL. His career was short-circuited with the Browns by the move of the franchise to Baltimore in 1995, but the 1994 season was a testament to the team Bill Belichick was assembling. The Browns finished 11-5, and sent Rob Burnett, Leroy Hoard, Pepper Johnson, Eric Metcalf, Michael Dean Perry and Turner to the Pro Bowl in Hawaii. Defensive coordinator Nick Saban (a Kent State alum who’d coached at several Ohio universities) had his defense performing at an elite level. Their signature performance that season was a 19-14 victory in Dallas against the defending Super Bowl champions. Sealing the deal was a tackle of tight end Jay Novacek by Eric Turner at the Browns’ goal line with time expiring. Novacek did appear to slip on the turf as he approached the end zone. Of course, that failed to dampen the joy of radio announcer Nev Chandler, who exulted that the Browns had “gone down to Big D and have defeated the Super Bowl champions!” Doug Dieken was heard chuckling with glee in the background. Led by E-Rock, the Browns players held their helmets high, jumping and running off the field.

Turner’s all-around game was improving to the point that, by 1994, he would make 1st team All-NFL. His career was short-circuited with the Browns by the move of the franchise to Baltimore in 1995, but the 1994 season was a testament to the team Bill Belichick was assembling. The Browns finished 11-5, and sent Rob Burnett, Leroy Hoard, Pepper Johnson, Eric Metcalf, Michael Dean Perry and Turner to the Pro Bowl in Hawaii. Defensive coordinator Nick Saban (a Kent State alum who’d coached at several Ohio universities) had his defense performing at an elite level. Their signature performance that season was a 19-14 victory in Dallas against the defending Super Bowl champions. Sealing the deal was a tackle of tight end Jay Novacek by Eric Turner at the Browns’ goal line with time expiring. Novacek did appear to slip on the turf as he approached the end zone. Of course, that failed to dampen the joy of radio announcer Nev Chandler, who exulted that the Browns had “gone down to Big D and have defeated the Super Bowl champions!” Doug Dieken was heard chuckling with glee in the background. Led by E-Rock, the Browns players held their helmets high, jumping and running off the field.

Turner had nine interceptions in 1994, and the Browns’ defense held opponents to an average of less than 13 points per game. The Browns made the playoffs and defeated the Patriots in the first round. This was the second time they’d beaten Belichick’s former team that year. (As a side note, 1994 was also the year Bill Belichick had hired a 23-year-old ballboy by the name of Eric Mangini.)

Eric Turner was not complacent; he had begun incorporating some of teammate Frank Minnifield’s analysis of receiver tendencies via the use of a laptop computer. He matured, allowing his well-known ‘mean streak’ on the field to fit into the scheme of the defense. This resulted in his being less likely to stand out individually than he had in college.

(Some joke that a DB’s lack of good hands are what prevent him from being a wide receiver. Maybe so. But to me, the emphasis of team goals over personal glory is a common difference between defensive backs and their diva cousins on the other side of the ball.)

The Browns defeated the Bengals going away on that day in 1992. Eric Turner, the previous year’s top draft pick… did not play due to injury. That was OK; his whole career was ahead of him. Quarterback Bernie Kosar burned the blitzing Bengals often, especially in the third quarter. Dad and I walked out of the Stadium amid the throaty barking of the buoyant home crowd. Bengals fans got a good-natured earful on their way out (“I bet it’s a looooong drive home after a loss!“) ("Back to Cincinnati: the land of the polite yet unfriendly!"). Once outside, an excited throng milled about near the exit. In the center- was that Jim Brown? Yep, just hanging out. He appeared willing to share pleasantries with anyone who wished to talk to him. Nice.

Eric Turner was released by the Baltimore Ravens before the 1997 season. He was a salary cap casualty, and the Oakland Raiders signed him. Turner was excited to play for the Raiders, and to be in his home state. He had made the Pro Bowl again in 1996, so he was still an elite talent. Tragically, he was already suffering from some intestinal issues by 1999. Reports in 2000 were that Turner had dropped 70 pounds and was battling intestinal cancer. He issued a public statement refuting this and stated he was not gravely ill. Perhaps this was to protect his family’s privacy, because Eric Turner passed away weeks later.

Gone, but will never be forgotten. Woven into the rich fabric of the tapestry of Browns history. Such will remain the memory of Cleveland Stadium, and that of an all-time Cleveland Brown, Eric Turner.

Thank you for reading.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)