Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Yesteryear: 1994 Playoffs vs. New England

Yesteryear: 1994 Playoffs vs. New England

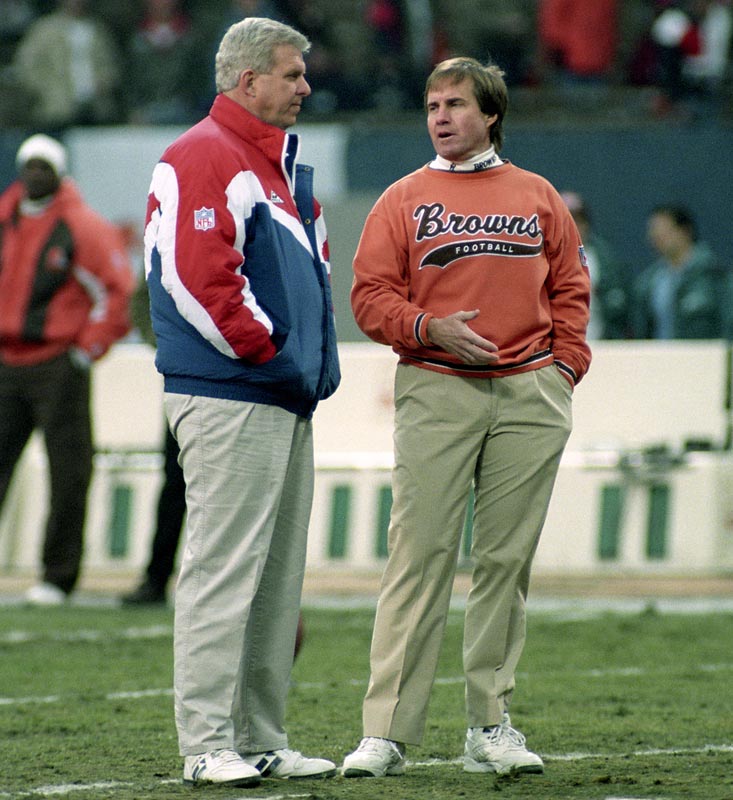

In 1990 the New England Patriots and Cleveland Browns were the worst teams in the NFL, finishing a combined 4-28. That same season the New York Giants, with their brain-trust of head coach Bill Parcells and defensive coordinator Bill Belichick, won their second Super Bowl in five seasons. Four years later, on New Year’s Day 1995, Parcells and Belichick reunited, this time as adversaries leading rejuvenated Patriots and Browns teams into an AFC Wild-Card Game at Municipal Stadium.

In 1990 the New England Patriots and Cleveland Browns were the worst teams in the NFL, finishing a combined 4-28. That same season the New York Giants, with their brain-trust of head coach Bill Parcells and defensive coordinator Bill Belichick, won their second Super Bowl in five seasons. Four years later, on New Year’s Day 1995, Parcells and Belichick reunited, this time as adversaries leading rejuvenated Patriots and Browns teams into an AFC Wild-Card Game at Municipal Stadium.

Belichick was the hottest assistant in the game when Art Modell tapped him to turn around a Cleveland club that had collapsed. Beset by age and injury, the 1990 Browns had fallen from the AFC Championship Game to 3-13 in one disastrous year. Belichick didn’t make friends early, alienating the town with his unceremonious jettisoning of popular veterans from the ‘80s- including Bernie Kosar. He didn’t win either, going 20-28 and failing to produce a winning record in any of his first three seasons on the job.

By 1994, however, Belichick had the team he wanted in place. A rebuilt defense held opponents to just 204 points during the regular season, one of the lowest totals of the sixteen-game era, while a maturing Vinny Testaverde guided a basic, ball-control offense. The special teams were solid in all areas- kicking, punting, coverage and returns. It was a team strongly reminiscent of the champion Giants, right down to some of the names like defensive leaders Pepper Johnson and Carl Banks.

The result was Cleveland’s first legitimate NFL contender of the decade. The ’94 Browns got off to a 6-1 start, their best in more than three decades. Their 11-5 regular-season record was their best since 1986, although it was good only for second place in the AFC Central behind Bill Cowher’s revived Pittsburgh Steelers. Cleveland would host the AFC Wild-Card Game, however; the franchise’s first home playoff game in five years.

If the situation in Cleveland was bad when Belichick took over, the New England team Bill Parcells came to in 1993 was downright radioactive. Plagued by organizational instability, a legacy of poor drafts and some tawdry off-the-field incidents, the Patriots compiled a 14-50 record from 1989-92. Parcells brought credibility and discipline, things that had been lacking in New England for years. Wins soon followed. After a 3-6 start in Parcells’s second season, the ’94 Patriots took off, winning their last seven and making the playoffs for the first time since 1986.

Unlike Belichick’s Browns or Parcells’s Giants, the Patriots were built around offense- specifically, the strong right arm of second-year quarterback Drew Bledsoe. The former number-one pick from Washington State triggered the league’s most prolific passing attack, throwing for 4,555 yards and 25 touchdowns. When Bledsoe wasn’t throwing interceptions- he fired a whopping 27, the most in the NFL by far- New England could move the football on any team in the league.

New England’s last loss of the season, nearly two months prior to the playoff, had been to the Browns in Cleveland. Bledsoe suffered through his worst game of the season that afternoon, completing just 20-of-43 for 166 yards and four interceptions and failing to produce a touchdown in a 13-6 Cleveland victory. To win the rematch the young quarterback would have to improve in every area, and do it on the road against one of the cagiest, most physical defenses in football.

On the other side of the coin, Bledsoe’s fellow former number-one pick Vinny Testaverde finally had his opportunity to shine. After the misery of his early career in Tampa Bay and the awkward succession of Bernie Kosar in Cleveland, Vinny was starting in a playoff game for the first time. His mandate was simple: pick your spots, avoid mistakes and don’t lose the football game. Bledsoe, on the other hand, would have to win it. For once in his NFL career, Vinny was at a distinct advantage.

And Vinny showed his hand on Cleveland’s first possession of the game. Back-to-back completions of 27 yards to Michael Jackson and 23 yards to Derrick Alexander were the key gains in an eight-play, 74-yard drive that carried to the New England 13 before bogging down. Matt Stover’s 30-yard field goal gave the Browns a 3-0 lead midway through the first quarter.

New England was not fazed by Cleveland’s opening sally. After extending their streak of touchdown-free quarters against the Browns to five, the Patriots finally broke the ice four minutes into the second period, when Bledsoe found running back Leroy Thompson out of the backfield for a 13-yard scoring flip. The teacher now led the student, 7-3.

The student’s response- and his team’s- took one possession. After taking over in good field position at their own 49, Cleveland regained the lead with a crisp seven-play, 51-yard march. Testaverde started the drive with two scrambles for fourteen yards then hit Michael Jackson twice for 29 more. On first and goal from the New England seven, Vinny scrambled right to avoid the rush of defensive end Mike Pitts and found his old Buccaneer teammate Mark Carrier in the back of the end zone. Stover’s extra point made it 10-7, Browns, midway through the second. A Matt Bahr field goal tied the score 10-10 at intermission.

Cleveland began to take control of the line of scrimmage on its opening possession of the second half. The Browns drove 46 yards to the New England 17-yard line, only to be waylaid by an Eric Metcalf fumble- their first and only turnover of the game. After the defense forced the Patriots to go three-and-out Cleveland regained possession at their own 21 with 8:21 remaining in the third period and started moving the football again. Testervarde got things going with passes of 25 yards to Leroy Hoard and 14 to Michael Jackson, having a big day with seven catches for 122 yards. Hoard finished the nine-play, 79-yard drive with a ten-yard touchdown blast off right tackle and it was 17-10 Cleveland with 2:21 left in the third.

Now Bledsoe had to lead his team from behind. But the young quarterback was finding the going tough against a Cleveland defense that was getting progressively more dominant as the game went on. Pressure forced Bledsoe into interceptions that killed back-to-back New England drives early in the fourth quarter. The second proved devastating. With the clock running down toward the seven-minute mark, Bledsoe threw too hot for running back Kevin Turner, who had the ball skim off his arms and into the hands of Eric Turner. The All-Pro safety- who had picked Bledsoe off twice in the November meeting- returned it to the New England 36 and the Browns had a chance to put it away.

With time and the score on their side, Cleveland proceeded on a six-play drive that chewed three-and-a-half minutes off the dwindling clock. Matt Stover’s second field goal, from 21 yards out, gave the Browns a 20-10 lead with 3:36 remaining. The Patriots weren’t quite done yet. They quickly drove to a field goal that made it 20-13 and then recovered an onside kick at their own 36-yard line with a minute-and-a-half to tie the score. But the Cleveland defense had gone too far to give this one up. Under relentless pressure Bledsoe inched his team out to near midfield, but misfired on four consecutive passes to quench New England’s final hope.

For the second time in two months the Browns had made life miserable for Drew Bledsoe. The youngster completed 21-of-50 and threw three interceptions, giving him seven in two quarters against Cleveland to go with one touchdown pass and a 44 percent completion percentage. Although Bledsoe was only sacked once he was hit on numerous occasions. Testerverde, meanwhile, barely stepped wrong. Hitting eleven consecutive attempts at one point, the former Miami Hurricane finished 20-of-30 for 268 yards with a touchdown and no interceptions. Like most playoff games, this one had been won by the team with the superior quarterback.

A week later the Browns were hammered in the AFC Divisional Playoffs, losing to Pittsburgh for the third time, 29-9. The 1994 Wild-Card Game is Cleveland’s last playoff at home and last playoff victory to date. The Patriots, meanwhile, went on to bigger and better things, first under Parcells and then under their old conqueror, Bill Belichick. That New Year’s Day game nearly sixteen years ago represented the dawn of a new era for the New England Patriots- and the brilliant sunset of the old Cleveland Browns as we knew them.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Hikohadon (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:24 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)