Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Homegrown Foes: The Forgotten Saga of the Cleveland Rams, Pt 2

Homegrown Foes: The Forgotten Saga of the Cleveland Rams, Pt 2

On December 17, 1945, Northeast Ohio toasted its world champion Cleveland Rams in a celebration that doubled as a mournful farewell. As many fans already knew, the team would soon be relocating to Los Angeles. Exactly 50 years later—December 17, 1995— the franchise that had once replaced those Rams now faced an eerily similar fate, as the original Cleveland Browns played and won their final game before a grieving crowd at Municipal Stadium. Clearly, those who don’t learn their history are doomed to repeat it.

On December 17, 1945, Northeast Ohio toasted its world champion Cleveland Rams in a celebration that doubled as a mournful farewell. As many fans already knew, the team would soon be relocating to Los Angeles. Exactly 50 years later—December 17, 1995— the franchise that had once replaced those Rams now faced an eerily similar fate, as the original Cleveland Browns played and won their final game before a grieving crowd at Municipal Stadium. Clearly, those who don’t learn their history are doomed to repeat it.

In Part One of this two-part series, we looked at the Cleveland Rams’ rise from pro football’s Depression-era doormat to its dominant, post-war champs, as rookie QB Bob Waterfield finally delivered Cleveland its long-sought NFL Championship in 1945. In typical Cleveland fashion, though, that’s where the story turns dark and complicated. Rams owner Dan Reeves, threatened by the arrival of a second Cleveland pro team in 1946 (Mickey McBride’s buzz-worthy Browns of the AAFC), decided to pick up stakes and start his franchise’s title defense anew in sunny California. Abandoned by the NFL, Cleveland football fans quickly turned their heartache into an unhealthy devotion to their new team, and the seeds were thus planted for an unforgettable showdown and the final act of this little Shakespearian drama: the 1950 NFL Championship Game.

Setting the Stage

Like all good dramas, there was a slow buildup. Between 1946 and 1949, the Rams and their former city existed in completely separate worlds, as far away professionally as they were geographically—kind of like a bitterly divorced couple. Out on the west coast, UCLA grad Bob Waterfield was back in his old comfort zone, but the L.A. Rams had no luck defending their title. The team would scuffle for several years and turn over most of its roster before getting back to the NFL Championship in 1949—a game in which the Philadelphia Eagles clubbed them by a 14-0 count.

Meanwhile, Cleveland had its new love: Otto Graham’s unstoppable Browns—winners of a Tom Emanski caliber back-to-back-to-back-to-back AAFC Championships. In 1950, the NFL finally took notice and swallowed up the AAFC, taking on the 49ers, Colts, and Browns as new franchises in the process. Despite Cleveland’s nice resume and star power, most national observers wrote them off as small fish from a tiny pond. The skeptics were abruptly silenced in the first week of the 1950 season, however, when Paul Brown’s boys shocked the world and massacred the defending champion Eagles 35-10 behind Graham’s 3 TDs and 346 yards passing.

Meanwhile, Cleveland had its new love: Otto Graham’s unstoppable Browns—winners of a Tom Emanski caliber back-to-back-to-back-to-back AAFC Championships. In 1950, the NFL finally took notice and swallowed up the AAFC, taking on the 49ers, Colts, and Browns as new franchises in the process. Despite Cleveland’s nice resume and star power, most national observers wrote them off as small fish from a tiny pond. The skeptics were abruptly silenced in the first week of the 1950 season, however, when Paul Brown’s boys shocked the world and massacred the defending champion Eagles 35-10 behind Graham’s 3 TDs and 346 yards passing.

A week later, on the other side of the country, the Los Angeles Rams pistol-whipped the New York Yanks 45-28. They were led not by Waterfield on this occasion, but by his much ballyhooed 24 year-old understudy, Norm Van Brocklin.

Far apart as they’d been all these years, the Rams and Browns had developed a curiously similar philosophy for winning. Rams head coach Joe Stydahar, much like Paul Brown, saw the passing game as the future of football. And like Brown, he had the guns to carry out his plans, as Waterfield and Van Brocklin would throw for over 3,500 combined yards by season’s end, with standout receivers Tom Fears and Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch catching over 120 balls and 14 touchdowns between them (numbers even superior to the Browns’ great Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie).

The Browns and Rams were also both at the forefront of integration. A year before Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers, Paul Brown had already signed the great Marion Motley and Bill Willis to join the inaugural Browns, saying he wanted the best players, regardless of race. The 1946 Rams also added two black players in the form of UCLA stars Woody Strode and Kenny Washington, but in that instance, the integration had actually been part of Dan Reeves’ contractual obligation with his team’s new home, the Los Angeles Coliseum.

In any case, with the NFL’s more traditionally-minded teams stuck in the lurch, the Rams and Browns each enjoyed six-game winning streaks during the fall of 1950. And more amazingly, when forced into tie-breaking divisional playoff games, both teams managed to upset opponents that had defeated them twice during the regular season (the Browns over the Giants, the Rams over the Bears). This set up the NFL Championship match-up that Clevelanders had been dreaming of—the Browns (11-2) against the Rams (10-3). Today vs. Yesterday, for all the marbles, on Christmas Eve.

The 1950 NFL Championship: "The Greatest Game I Ever Saw"

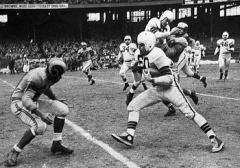

As if there weren’t enough drama already, the Rams had lost Van Brocklin to broken ribs in the Bears game, meaning that Bob Waterfield would be under center and center-stage for his first game at Municipal Stadium since he’d gone out a champion five years earlier. He was in Cleveland again, it was Christmas time again, the title was on the line again, and he was wearing the same uniform. But this time, Waterfield and the Rams would be the villains. That surreal shift in the storyline wasn’t lost on anyone, but the prodigal son’s return was just one of a dozen reasons why this game was every bit as epic as the Ice Bowl, Super Bowl XXV, or any other more commonly referenced NFL classic.

The problem is, this was 1950, and football was still decidedly the nation’s second love. Case in point, just two years after piling 86,000 people into Cleveland Stadium for one game in the 1948 World Series, only 30,000 passed through the turnstiles at the same venue to see the Browns meet their predecessors for the NFL title. Still, those in attendance would have a story to tell for generations to come-- about the day Bob Waterfield came back to town and Automatic Otto was up to the challenge.

“Looking back on it, it was the greatest game I ever saw,” Paul Brown later said. “Not just because of the game itself, but because of the tremendous exhibition of passing both teams put on. Both of us were the leaders in a modern day revolution of switching the emphasis from running to passing.”

For his part, Waterfield silenced the Cleveland hecklers with almost LeBron-like ruthlessness in the first minute of the game, connecting with Glenn Davis for an 82-yard touchdown strike on the Rams’ opening possession. Predictably, Graham responded swiftly, finding Dub Jones for a 27-yard score to even things up. But a banged-up Cleveland defense broke down again, as Rams running back Dick Hoerner capped a long drive with a 3-yard touchdown run to make it 14-7 Los Angeles after one quarter. Graham would hit Dante Lavelli for six before the half, but Lou Groza missed the extra point, giving L.A. a narrow 14-13 edge at the break. Groza would eventually redeem himself.

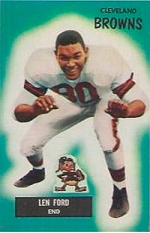

For Cleveland, the real highlight of the first half didn’t even involve a specific play, but a player. In a game stacked with future Hall of Famers (8 Browns and 4 Rams, to be exact), Browns defensive end Len Ford was easily the most heroic. Still feeling the effects of a career-threatening hit he’d taken from the Cardinals' Pat Harder back in October, Ford was finally back in uniform (though 20 pounds below his playing weight) and begged Paul Brown to put him in the game. A frustrated Brown finally relented, and Ford wouldn’t let him regret it. In one series alone, Ford sacked Waterfield and crushed Ram runners in the backfield for two other big losses. His efforts also helped pressure a flustered Waterfield into four interceptions on the day, compared to just one for Graham.

For Cleveland, the real highlight of the first half didn’t even involve a specific play, but a player. In a game stacked with future Hall of Famers (8 Browns and 4 Rams, to be exact), Browns defensive end Len Ford was easily the most heroic. Still feeling the effects of a career-threatening hit he’d taken from the Cardinals' Pat Harder back in October, Ford was finally back in uniform (though 20 pounds below his playing weight) and begged Paul Brown to put him in the game. A frustrated Brown finally relented, and Ford wouldn’t let him regret it. In one series alone, Ford sacked Waterfield and crushed Ram runners in the backfield for two other big losses. His efforts also helped pressure a flustered Waterfield into four interceptions on the day, compared to just one for Graham.

Still, the Browns found their own ways to shoot themselves in the foot, nearly choking the whole game away in a matter of minutes late in the third quarter. Leading 20-14 after another long Graham-to-Lavelli touchdown, Cleveland failed to stop Hoerner on a fourth and goal run, putting L.A. back on top. Then, on the Browns next play from scrimmage, Marion Motley was stripped of the ball inside the Cleveland 10 yard-line, and the Rams Larry Brink was Johnny-on-the-spot, scooping it up and jogging in for another score: 28-20 Rams.

The restless crowd now turned to Graham to save the day, and he did so in creative fashion. With Motley mostly relegated to blocking duties by the tough Ram line, and L.A.’s defensive backs playing deep to cut off Lavelli and Jones, Graham found himself with plenty of real estate to put his own legs to use. While Otto went 22-33 for 298 yards and 4 touchdowns on the day, his most impressive stat may have been his Vick-like 99 rushing yards on just 12 carries. Forced to adapt to this added wrinkle in the Cleveland offense, the Rams looked helpless during the Browns final crunch-time drives. After Graham found Rex Bumgardner for a 14-yard score to make it 28-27, he quickly had his team deep into Ram territory again with just minutes to play and the title on the line.

The Browns were already within Lou Groza’s kicking range when Graham, not seeing any open receivers, tucked the ball under his arm and looked to scrape together some extra yards. The next thing he knew, he was face-first in the turf, and Bill Lazetich—one of just a handful of Ram players left from the Cleveland days—had fallen on the football. This was 30 years before “Red Right 88” or “The Fumble,” but Graham was only too aware of the potential long-term consequences of what he’d just done.

“I wanted to dig a hole right in the middle of the stadium, crawl into it, and bury myself forever,” he later said.

In a famous bit of Browns mythology, though, Paul Brown was not concerned (despite the fact that the Rams could wrap up the game by converting a first down and running out the clock). “Don’t worry,” he supposedly told Graham after the play. “We’ll get it back. We’ll win this thing yet.”

In a famous bit of Browns mythology, though, Paul Brown was not concerned (despite the fact that the Rams could wrap up the game by converting a first down and running out the clock). “Don’t worry,” he supposedly told Graham after the play. “We’ll get it back. We’ll win this thing yet.”

Meanwhile, Bob Waterfield was entering the deepest stage of his bizarro déjà vu, trotting back on to the field on the verge of his second championship triumph in Cleveland, but being perceived now more as an angel of death than a savior. The Rams led 28-27 and Waterfield’s stat line had verified his greatness in the absence of Van Brocklin: 18 of 31 for 312 yards and a touchdown. Bob had also missed a very short field goal back in the second quarter, but it looked irrelevant now.

That’s when Rams coach Joe Stydahar did what many coaches today would do in the same situation. He got conservative. More concerned about Waterfield’s four picks than his numerous successes, Stydahar called three consecutive straight-ahead run plays, each easily snuffed out by Len Ford and the Browns defense. With less than two minutes to play, Waterfield was finally permitted to move the ball down field… via the punt. Graham and the Browns would now have it at their own 32 yard-line with 1:50 on the clock, trailing by a single point.

It was time for Otto Graham to cement his legend. On the first play of the drive, he scrambled loose for 14 yards and a first down. Next came a 15-yard laser to Rex Bumgardner to move the Browns into Ram territory. Then, a 16-yard strike to Dub Jones, putting Cleveland at L.A.’s 23 yard-line with under a minute to go. Lou “The Toe” Groza wasn’t warming his leg up on the sidelines, but that’s only because he was playing left tackle throughout the drive. Graham knew they were already well within Groza’s range, but he confidently kept up the attack, hitting Bumgardner again on a sideline pattern to the 11, then keeping it himself for a one-yard dive to set up Lou for an optimal chip shot.

With 28 seconds left, Groza planted himself right about where Waterfield had missed his field goal earlier, and with a gusting December wind at his back, calmly pendulum punched the ball through the center of the uprights to give the Browns a 30-28 lead.

As they had done five years earlier for the Rams, the Cleveland Stadium fans went ballistic, many rushing the field despite the ample time still remaining. When Groza finally did kickoff, Los Angeles advanced the ball to their own 46, with only time enough for a heave or two down the field. For reasons only Stydahar could explain, he chose this moment to insert Van Brocklin, broken ribs and all, into the game for the first time. Maybe Norm had the better arm or the golden touch. In any case, the roll of the dice failed, as the Browns Warren Lahr leaped up and picked off Van Brocklin’s wounded duck to seal the game and bring the NFL Championship back to Cleveland— along with exorcising a few demons in the process.

Amidst the celebratory madness in the locker room after the win, coach Paul Brown was pleasantly out of character. "This is the gamest bunch of guys in the world," he said. "Next to my wife and family, these guys are my life. What a Merry Christmas they've made it!"

Bob Waterfield’s comment was considerably less merry but maybe even more telling. “It was just one of those things,” he said, still trying to make sense of it all.

The cover of the Plain Dealer on Christmas morning, 1950, featured a photo of Groza’s game-winning kick—its trajectory traced by a dotted line. “Bravo Browns!” read one headline. “All Cleveland Proudly Salutes Our New World Champions.” The Rams were L.A.’s problem now. Cleveland was more than happy with its consolation prize.

Final Fun Factoids of the Cleveland Ram Legacy

--Though it’d be great for the story to end there, the Rams actually got their revenge one year later, with Van Brocklin at the helm, beating the Browns 24-17 at the L.A. Coliseum for the 1951 NFL Championship. It would be the last championship the Rams would ever win for Los Angeles. In a weird bit of trivia, the Ram franchise has won exactly one title in each city it’s been in: Cleveland (1945), Los Angeles (1951), and St. Louis (1999).

--Ex-Clevelander Daniel Reeves remained the principal owner of the L.A. Rams up until his death in 1971, after which Baltimore Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom assumed control of the franchise. In turn, Rosenbloom passed the Colts along to Robert Irsay—the man who would eventually move the franchise to Indianapolis, turning the city of Baltimore into any disgruntled NFL owner's ideal bargaining chip.

--And here's the best nugget of all. In 1953, the Rams' original owner-- Cleveland lawyer Homer Marshman-- wanted to make up for the mistake of selling the Rams to Dan Reeves 12 years earlier. So he got some investors together and bought the Browns from Mickey McBride (who was losing his patience with Paul Brown) for a reasonable $600K. Then, in 1961-- twenty years after selling the Rams to the man who wound up moving the team out of Cleveland-- Marshman agreed to sell the Browns for $4.3 million to a young businessman by the name of Modell.

Again, those who don’t learn their history…

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)