Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Burning My Draft Card

Burning My Draft Card

I’m about to make a confession that could very well get me killed in this town, for I am about to stand atop the Terminal Tower and jeer an established, embraced cavalcade of hope that endures in a tempest of despair. Against my better judgment, I will chew up a Snickers bar and then spit it in the face of an annual Cleveland tradition.

I’m about to make a confession that could very well get me killed in this town, for I am about to stand atop the Terminal Tower and jeer an established, embraced cavalcade of hope that endures in a tempest of despair. Against my better judgment, I will chew up a Snickers bar and then spit it in the face of an annual Cleveland tradition.

I hate the NFL Draft.

Not just the draft itself, but everything before and after.

I despise Mel Kiper and his tower of hair. I loathe the endless predictions by the “experts” as to which player will be drafted when and how his “stock” has dropped either because it’s raining in Paraguay or he sneezed too hard over the weekend.

Then there’s the crackerjack “analysis” of the draft, where the afore-mentioned “experts” somehow justify a way to “grade” teams on how well they did in the draft without any of the players they drafted actually putting on a helmet, followed by the “you-can’t-sign-until-the-guy-drafted-ahead-of-you-signs” song and dance that plays out through the summer.

At the same time, I can completely understand why football fans – particularly Browns fans – love Draft Day. It’s perfectly situated to break up the long offseason with a Hungry Man Dinner-sized football fix, like having your birthday exactly six months before Christmas.

More than that, it’s a day of optimism, when there’s nothing but potential and high spirits and you can honestly believe that the Browns have acquired that one player who will take them to the promised land. Which may actually be Mentor, as it turns out.

Now, I certainly don’t want to be a buzzkill. I completely respect anyone who gets fired up about the draft and hosts murder-mystery dinner parties revolving around it or whatever else goes on. And I wish I could be as optimistic as others that the Browns will be able to dramatically improve their team in one day.

But I just can’t.

Why not, you ask?

To answer that, let’s play a little game. I’m going to ask you a series of questions. You’re invited to guess the answer, then attempt not to thrust your index finger through your eye and swirl it around.

As anyone holding a bottle of Bud Light would say, here we go:

It’s 2002. The Browns are coming off a promising 7-9 season following a 5-27 mark in their first two as an expansion team. Butch Davis, starting his second year as head coach after being snatched away from the University of Miami like Elian Gonzalez, still has many holes to fill. None is more important than running back, at which the 2001 Browns featured the feckless one-two punch of James Jackson and Jamel White. Luckily, there are several nice players available in the college draft.

You’re Butch Davis – do you pick:

a) Clinton Portis, RB Miami

b) Brian Westbrook, RB, Villanova

Or, with your defense still under construction, do you opt for a building block in your secondary with:

c) Ed Reed, S, Miami

Any of these answers would have been correct, particularly considering Butch’s not-so-secret compulsion to turn the Browns into an NFL version of the Miami Hurricanes. Yet with all three of these future perennial Pro Bowlers available, Davis went another way, selecting William Green out of Boston College with the 15th pick, the first running back taken.

Hurricanes. Yet with all three of these future perennial Pro Bowlers available, Davis went another way, selecting William Green out of Boston College with the 15th pick, the first running back taken.

Certain the “character” and “substance abuse” problems that have followed Green throughout his athletic career will vanish once a disciplined and forthright coach like Davis takes him under his wing, Butch is thrilled with the selection.

Skip ahead three years. Westbrook is about to become the most versatile running back in the NFL and an annual top-five fantasy pick. Portis will enjoy his fourth straight 1,000-yard season and third of better than 1,500. Ed Reed is on his way to becoming the most dominating safety in football. And Ryan Seacrest will continue to make money, though no one’s quite sure why.

Meanwhile, in 2005, William Green – with his domestic stab wound now healed and his arrest for drunken driving and marijuana possession nothing but water under the bridge – carries the ball 20 times for 78 yards for the season and never plays in the NFL again.

It’s now nine years since that draft. Portis and Westbrook just keep on keepin’ on and Reed is still intercepting whomever the Browns decide to put at quarterback.

To quickly hit on some other highlights of Butch Davis’ draft history, let’s switch the format of our little game.

In the mind of Butch Davis and the Cleveland Browns in 2001:

Gerard Warren ___ LaDainian Tomlinson

a) Will clearly have a better NFL career than

b) Is more likely to lead the Browns to the playoffs than

c) Reflects the needs of the Browns more accurately than

In this case, all three answers are correct. And all three answers would also be correct when replacing LaDainian Tomlinson with Richard Seymour, Santana Moss, Todd Heap, and Reggie Wayne.

Here’s another variation – in the second round in 2001, Butch decided to select a receiver. Let’s compare notes on the top two available candidates:

Quincy Morgan

- From Kansas State, which, as we all know, has regularly churned out skill-position superstars

- Would fit right in with the equally underwhelming wide receivers the Browns already have

- Had hands surgically removed in high school

Chad Johnson

- An arrogant jackass, an important qualification to play on a Butch Davis team

- Was born in Miami and at some point probably watched The Birdcage, making him instantly appealing to anyone obsessed with all things South Beach

- Actually capable of catching passes

Apparently drawn to the mystical nature of the letter Q that starts his name, Butch eschewed common sense and opted for Morgan. Seven 1,000-yard seasons, 66 touchdowns, a bizarre name change, and a Dancing With the Stars appearance later, Johnso-Cinco has made Quincy Morgan as forgettable as a Mesopotamian high school dropout.

A year later, Butch also deemed that Andre Davis was a better wide receiver than either Antwan Randle El or Deion Branch and that Andra Davis was a better linebacker than Scott Fujita.

But this is not to pick on good ol’ Butch Davis, who has since moved on and is the process of turning the North Carolina program into a menagerie of southern-fried thugs emerging from a haze of sky-blue pot smoke with just enough talent to score a grease-stained invitation to the Chick-Fil-A Bowl each year. The trend goes much deeper.

Before Butch ever hit town, we’d decided Courtney Brown was far better suited for the NFL than Jamal Lewis, Brian Urlacher, Shaun Alexander, and John Abraham. We decided to use Tim Couch as a primary building block for the franchise instead of Donovan McNabb, Edgerrin James, Torry Holt, or Champ Bailey.

Clearly, over the past 12 years, Draft Day has served little more purpose for us than a Messin’ With Sasquatch commercial. But that’s only because we made the mistake of having somebody in charge who didn’t know what he was doing when we brought in Dwight Clark. And then Butch Davis. And then Phil Savage. And then George Koninis.

But it’s not just us, right? It happens to everybody.

Let’s randomly pick another team and take a look at their success rate – say, the Old Browns.

We need look no further than their last draft in 1995, when they’d fallen in love with Penn State tight end Kyle Brady, spelling out his name in peas on their dinner plates and sending him little notes spritzed with perfume. Then, when the New York Jets shockingly took Brady a pick before, the Browns panicked like a hormonal bride-to-be in Filene’s Basement. Paralyzed by uncertainty and certain there were no other players out there as talented and hunky as Kyle Brady they traded down and settled for Ohio State linebacker Craig Powell, whom even John Cooper had never heard of.

Whew – disaster averted. It wasn’t as if the Browns could have done any better. It’s not as if they could have stayed put and drafted Warren Sapp or Ty Law or Derrick Brooks. (And yet, since any of these picks would have simply helped the Baltimore Ravens be even more dominant defensively over the next decade, let’s all be thankful they didn’t.)

But the Panic of ’95 was far from an isolated incident.

Ed King over Roman Phifer. Lawyer Tillman over Carnell Lake. Van Waiters over Bill Romanowski. Gregg Rakoczy over Tim McDonald and Christian Okoye.

That little toe-tapping string took place in a dazzling four-year period during which the Browns brilliantly set up their 1990s fall. And, remarkably, none of those mistakes was the true Hindenburg of any particular Draft Day.

For that, let’s go to the lightning round of our little game.

It’s 1987. You’ve just traded one of the stars of your defense, linebacker Chip Banks, to get the fifth overall pick in the draft and are looking to bolste r that side of the ball for a run to the Super Bowl.

r that side of the ball for a run to the Super Bowl.

Do you select:

a) Shane Conlan, LB, Penn State

b) Jerome Brown, DT, Miami

c) Rod Woodson, DB, Purdue

Any choice would be winning. Instead, you opt for door No. 4 and the infamous “Mad Dog in a Meat Market.” Thus, little-known Duke linebacker Mike Junkin began his legendary 15-game career as a Brown, defined by the label put upon him by a Browns’ scout who’s now the assistant manager at a Hardee’s in Coshocton.

By the time the 1988 draft rolls around, it’s clear that your Junkin pick was a) not well received by literally any carbon-based life form, and b) a complete fucking disaster. So the pressure’s on to get it right this time. Now, both your offense and defense are starting to age a bit after two AFC title-game losses, and you’re looking for players on either side of the ball who can carry the team two or three years down the line.

Again, remembering the mistake you made with the Mad Dog a year earlier, do you pick:

a) Chris Spielman, LB, Ohio State

b) Ken Norton, LB, UCLA

c) Thurman Thomas, RB, Oklahoma State

d) Dermontti Dawson, C, Kentucky

It’s like Hometown Buffet on a Sunday afternoon. It all looks so good, you don’t know where to start.

But instead of heaping some steaming hunks of pot roast or buttery mashed potatoes on your plate, you opt for a bowl of ranch dressing with maggots crawling out of it and pick Florida linebacker Clifford Charlton.

The primary benefit of this selection is that it actually makes the Junkin pick look good. Charlton started one game, collected one sack, and was out of football within two years. Well played.

By the time the 1990 season begins, both Junkin and Charlton are not only off the team but completely out of football, meaning you have a grand total of zero first-round draft picks from 1983-1988 on your roster. If you’re competent in the least with those picks, you have three-to-five extra starters in your 1990 talent pool. (And considering the ’90 team only had about eight starter-caliber players on the roster to begin with, that extra help could have come in mighty handy.)

Sadly, there’s more. You select wide receiver/sprinter Ron Brown in 1983, hoping he can be that burner your passing game has been seeking since Reconstruction. Instead, he screws you, opting out of football to train for the 1984 Olympics. And when he does return to football with the Rams two years later, he’s as mediocre as he would have been had he stuck with football in the first place.

But no big deal. All it cost you was Roger Craig or Albert Lewis, just like all bloated defensive lineman Keith Baldwin cost you was Andre Tippett or Mark Duper the year before.

Even when we play it safe, we get screwed. The last time we picked a Heisman Trophy winner was USC tailback Charles White in 1980. Tough to argue with that, right? At least until five years later when super-centers Ray Donaldson and Dwight Stephenson and defensive end Rulon Jones – all of whom you passed over – are racking up Pro Bowl invitations and Charles White is using cigarettes as currency after being popped for cocaine possession not long after being cut by the Browns.

In some ways, this game can be fun. You can imagine the Browns of the 1980s with the players we could have had instead of the players we did.

Dominant defensive tackle Fred Smerlas could have been a Brown, but we opted for wide receiver Willis Adams. We could have kept Mark Gastineau from making Bernie Kosar spit up blood (instead of cornerback Lawrence Johnson) or had Al “Bubba” Baker in his prime (instead of punter Johnny Evans).

Picked fifth overall in 1975, d-lineman Mack Mitchell became the Gerard Warren of the ’70s when we picked him over linebacker Robert Brazile (a seven-time Pro Bowler with the Oilers) and defensive tackle Gary Johnson (a four-time Pro Bowler with the Chargers). Meanwhile, Hall of Famers Dave Casper and Jack Lambert may have led their teams to multiple Super Bowls, but, hey, instead we got tackle Billy Corbett, a legend at Johnson C. Smith University who – egads! – never played a down in the NFL.

We bypassed Hall of Fame offensive linemen in Joe DeLamielleure and Dan Dierdorf to land tailback Bo Cornell – whose Browns’ career amassed 20 yards on 18 carries – and wideout Steve Holden, who almost picked up 1,000 receiving yards. In his career.

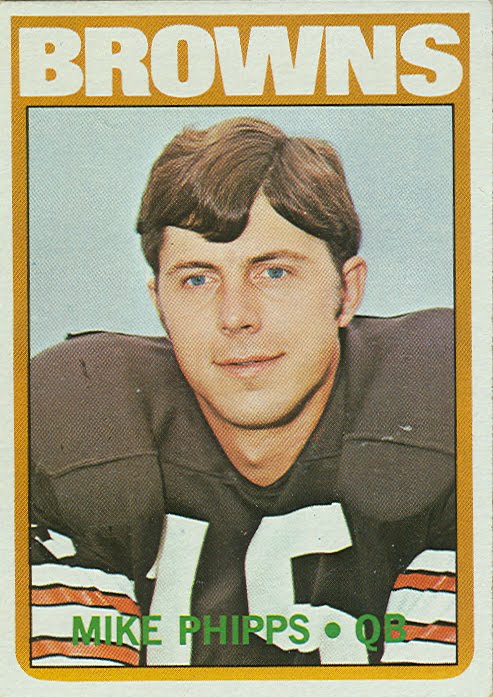

Which leads us to where many people think this all started: the trading of Paul Warfield to select quarterback Mike Phipps in 1970. The primary sin wasn’t so  much selecting Phipps (particularly since the draft class was relatively weak that year) as it was giving up Warfield. But to their credit, at this point the Browns knew that poor Bill Nelsen’s knees were nougat and they were going to need a quarterback in the near future.

much selecting Phipps (particularly since the draft class was relatively weak that year) as it was giving up Warfield. But to their credit, at this point the Browns knew that poor Bill Nelsen’s knees were nougat and they were going to need a quarterback in the near future.

Yet had they waited a year rather than giving up a Hall of Fame receiver to try to solve the problem right away, they could have had Ken Anderson, whom they passed up anyway to pick Michigan receiver Paul Staroba. Sure, Anderson may have gone on to be one of the premier quarterbacks in the game for the next decade, but the one catch Staroba made as a member of the Browns was something to behold.

The bottom line is that for all the research and analysis that goes into every single selection, the NFL draft is still the most beautifully choreographed crap shoot in sports.

Every team hits and misses, some (the Browns) more than others (the Steelers and Ravens).

For every Joe Montana, there’s a Tony Mandarich. For every Peyton Manning, there’s a Ryan Leaf.

Or perhaps more symbolically for us, for every Joe Thomas, there’s a Brady Quinn.

But if it’s truly a crap shoot, doesn’t the law of averages conclude that you should occasionally win a round? And with all due respect to Joe Thomas and maybe Alex Mack and Joe Haden, they’re just not franchise-altering players. For the myriad of Mike Phippses and Tim Couches we’ve selected over the last 40 years, shouldn’t we just once have landed a Tom Brady?

But please don’t let me sap the pleasure out of your Draft Day(s) experience the way John Wilkes Booth pumpkin-bombed Our American Cousin. By all means – celebrate perpetual hope. Embrace potential. Imagine the autumn that could be. Envision the names that could be etched in the Browns’ new Ring of Honor 15-20 years from now.

This little four-decade slump is bound to end sometime. In fact, maybe it already has ended and we just don’t know it yet.

But until we’re sure, as much as I’d like to partake in the orgy of football excitement this week, there have been too many mad dogs and way too many meat markets for me to get excited about the Browns being on the clock.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)