Browns Archive

Browns Archive  The Best That Never Was

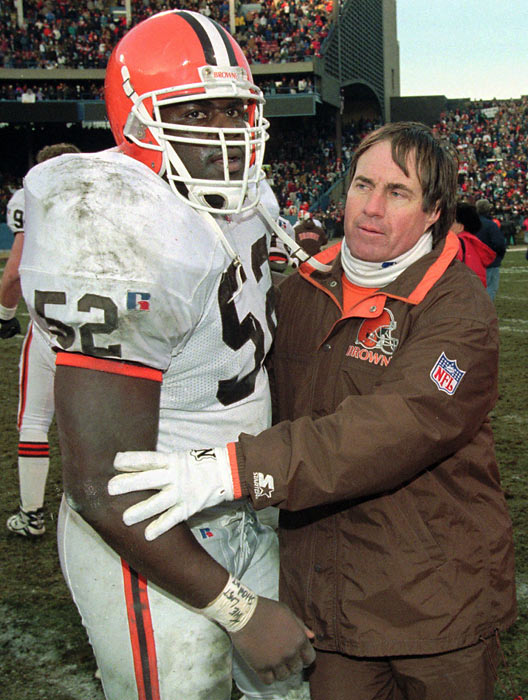

The Best That Never Was

We often forget that when Art Modell blasted a silver bullet into our souls, execution-style, in November of 1995, he didn’t just take away our football team.

He took away a football team that was supposed to go to the Super Bowl.

Hysterical in retrospect, the 1995 Browns were considered a genuine title contender as the sweaty days of August slogged toward September. And not just by the same overanxious fans that chanted “Super Bowl!” at Braylon Edwards and Derek Anderson on the first day of the 2008 training camp, but by celebrated prognosticator Paul Zimmerman (“Dr. Z”) of Sports Illustrated.

Dr. Z cited the “anger factor,” based on the Browns’ inability to defeat the hated Steelers in any of their three marquee matchups the year before, the final two of which were for the division title and then a trip to the AFC Championship.

The Browns may well have been the second-best team in the AFC in 1994, and in 1995, with Buffalo’s early ’90s dynasty fading, they were the heir apparent to become the class of the conference.

They’d lost Michael Dean Perry, the anchor of the defense for so many years, but had added key pieces in nose tackle Tim Goad and fellow lineman Larry Webster. With all the other key starters returning, there was no reason not to expect the defense to pick up where it left off after a dominating 1994 season, even after the departure of defensive coordinator Nick Saban (yes, that Nick Saban) for the head-coaching job at Michigan State.

Mostly though, excitement abounded upon the arrival of superstar free-agent wide receiver Andre Rison, the first true playmaker on offense the Browns would have since Greg Pruitt’s prime in the mid-1970s. With Rison to bolster the passing game, plus the arrival of former Houston tailback Lorenzo White to complement Hoard and veteran leader Earnest Byner in the backfield, the Browns’ offense was clearly better.

Meanwhile, the Steelers had lost a handful of key players to free agency and the rest of the division was a joke, with the Bengals coming off a 3-13 season, the Oilers in disarray, and the expansion Jacksonville Jaguars just figuring out how to fasten their chinstraps. To be sure, there were other strong teams in the AFC, but none clearly better than Cleveland.

This was further demonstrated over the first four weeks of the ’95 campaign. After a last-minute loss to a strong New England team on the road in the opener, the Browns won three straight, highlighted by a blowout victory over the 3-0 Kansas City Chiefs (bound for a 13-3 record) in Cleveland in Week Four in what would be the last truly sweet moment of the old Browns regime.

As October began, the Steelers were struggling and the Browns were alone in first. This did indeed look like a Super Bowl team.

Yet a month later, on the day news broke about the team moving, the Browns stood at just 4-4 – still tied for first in the division, but hardly looking like a playoff team. The tiny cracks that had been ignored in the first four weeks began to break open in the next four.

The defense, the foundation upon which everything else was built, was being rolled on, allowing more than 400 total yards in a game three times in the first six weeks after it’d happened just once in all of 1994.

The offense was moving the ball, but not scoring points. The running game that had defined the attack the year before was stalling.

Electrifying Andre Rison had only caught 17 passes in the first seven games and hadn’t scored a touchdown. Take away two interception returns for touchdowns in the Kansas City game and the Browns’ much-ballyhooed offense had failed to score more than 22 points in any of the first seven contests and was starting to turn the ball over at an alarming rate.

Though his statistics did not warrant indictment, Vinny Testaverde was made the scapegoat. Through seven games, Testaverde had played well, posting a strong quarterback rating of 89.7 with 10 touchdown passes and only three interceptions while completing 57% of his passes in what was shaping up to be the finest season of his embattled career.

After a humiliating loss to the expansion Jaguars at Cleveland Stadium to drop the Browns to 3-4, Testaverde was benched and the offense was handed to rookie quarterback Eric Zeier, who’d looked marvelous in the preseason – and, believe it or not, had been likened to Brian Sipe by Sports Illustrated.

And for one day, Zeier indeed resembled the second coming of Sipe. On the last Sunday in October, roughly 12 hours after the Indians lost Game Six of the 1995 World Series in Atlanta, Zeier directed the Browns to a desperately needed victory in Cincinnati, throwing for 310 yards and running for 44 more. Andre Rison caught seven of Zeier’s throws for 173 yards, and the Browns piled up 480 total yards, surviving a bizarre Bengal comeback in the final seconds to win in overtime and pull back to .500.

While perhaps still not a Super Bowl-caliber team, the Browns had showed signs of life and were in the thick of the race for a playoff berth in a wide-open AFC.

Seven days later, just before the Browns’ home game with the Houston Oilers, word of the move leaked. Needless to say, everything changed.

The games that followed were little more than exhibitions – rage-spewing moratoriums at home and fanciful circus-like novelties on the road. The object of the remainder of the season for both the players and coaches became not about winning games, but simple survival.

For the record, the Browns lost seven of their last eight to finish at 5-11. Eric Zeier’s fantastic day in Cincinnati turned out to be one of the most maddening mirages in team history, and within two weeks, Testaverde returned to the lineup and Zeier began his quick fade into oblivion.

Had the 1995 Browns turned a corner that gray afternoon in Cincinnati? Had the space-time continuum not veered off toward Hades seven days later, would they have made a run at the division title? Were they about to come together and become the team everyone thought they would be back in August?

As it happened, that’s exactly what the Steelers did. After starting 3-4, they went on to win their next eight games to clinch the division, which, with the Browns’ collapse, quickly became a comedic wasteland akin to NBC’s “Must See TV” Thursday sitcom lineup.

Then, cashing in on a stunning upset by the 9-7 wild-card Colts over 13-3 Kansas City in the divisional playoffs, the Steelers wound up going to the Super Bowl that year with an 11-5 record, then came within one Neil O’Donnell of defeating the favored Cowboys in the big show.

Could it have been the Browns? Were it not for Art Modell vacating his soul, could 1995 have been defined not by the loss of the Browns, but rather by the euphoric possibility of seeing the Indians in the World Series and the Browns in the Super Bowl within a three-month period?

There are arguments to be made for both sides and many hypothetical angles to explore. But when the proverbial dust settles, we’ll never know if the 1995 Browns could have been something special.

In reality, we’re left with the memories of a shattered team and a horrible experience, made all the more painful by contemplating what might have been.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)