Browns Archive

Browns Archive  Why We Are The Way We Are

Why We Are The Way We Are

Let’s get a spot diagnosis out of the way right off the top.

Let’s get a spot diagnosis out of the way right off the top.

As Cleveland fans, we are both schizophrenic and bipolar.

And it doesn’t take much reflection to pinpoint the moment our condition began. While our perpetual dry-hump with suffering dates back to the mid-1960s, the duel that takes place within our own psyche each time a Cleveland team plays truly started 25 years ago this week.

For in the course of a matter of days in January of 1987, we experienced perhaps the ultimate high and the ultimate low in on-field Cleveland sports history.

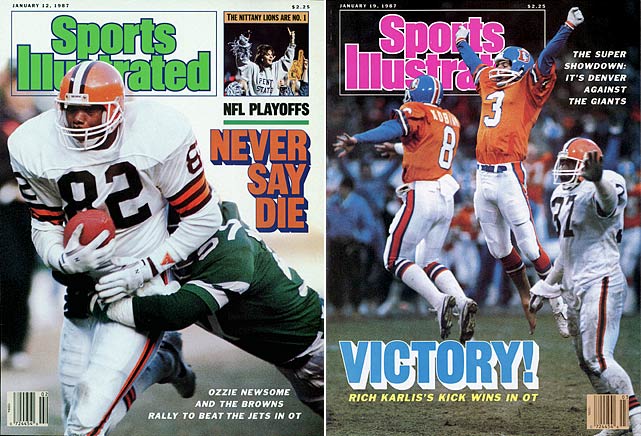

I’m talking, of course, about two Browns playoff games that have been labeled with code names as if they each were a covert military operation designed to overthrow the Castro regime: “Jets Double Overtime” and “The Drive.”

On paper, they’re essentially the Osmonds of Browns’ postseason history, appearing almost identical from a distance: both were played in Cleveland, both went to overtime after a tying score in the last minute of regulation, both finished with the identical final score.

January 3 was a divisional playoff: Browns 23, Jets 20. January 11 was the AFC Championship: Broncos 23, Browns 20.

Think about the dichotomy of those respective moments - a miracle and a tragedy. Then consider how close they came to one another. It was like losing your virginity one weekend and then catching gonorrhea the next.

That week laid down the backbeat for the next quarter-century of our lives as Cleveland fans. There certainly have been a handful of golden moments worth celebrating and cherishing since then, but each and every one of them was followed almost immediately by a spirit-crushing roundhouse kick to the soul.

Thus, we’ve become the twisted sports equivalent of Pavlov’s dogs. Whenever a Cleveland team excels - making the playoffs, winning a division, snapping a 26-game losing streak, etc. - we reflexively wince and wait for the anvil to drop upon our heads.

Consequently, a painfully simple catechism has evolved and somehow we’ve come to accept it without discussion:

For every Jets game, there must be a Broncos game.

Some would say that’s being negative. It’s not. It’s instinct. It’s a psychological and emotional security system that no one but us truly understands. And until there’s a victory parade down Euclid Avenue, it’s necessary to our survival - in a way, our own scarlet letter from that fateful week 25 years ago.

Think back to those two January weekends. The memories, while vivid, are less like home movies and more like iconic portraits of history: one weekend was the American soldiers pushing up the flag at Iwo Jima and the other was the Zapruder Film.

My most vivid memory of “Jets Double Overtime” is running up the stairs to my bedroom, burying my face in the carpet, and bawling my eyes out. Granted, I now react this way at some point during any Browns game, but even at the tender age of 10, tears hadn’t come often in 1986.

So when Jets running back Freeman McNeil bounced outside and into the end zone from the Cleveland 25 to put heavy underdog New York ahead 20-10 with just over four minutes left in their divisional playoff game with the Browns, I genuinely believed the world had come to an end.

With my cheeks still salty with tears and my eyes a deep red, I went back downstairs not with any hope that the Browns might mount a comeback, but the way people go to funerals: to acknowledge the reality of death and say good-bye. And sure enough, the Browns were still lifeless, facing second-and-24 deep in their own territory with time running out.

Then mullet-haired Jets defensive lineman Mark Gastineau plowed headfirst into Bernie Kosar’s back after he’d released another fruitless pass, giving the Browns a belated Christmas gift in the form of an unearned first down. They turned Gastineau’s lunacy into a touchdown, followed by a quick defensive stop and then another amazingly quick scoring drive (highlighted by Webster Slaughter making one of the greatest catches in Browns history) to send the game to an overtime they dominated the way Google owns search-engine optimization.

After missing a potential game-winning, chip-shot field goal for no apparent reason other than to watch us hemorrhage a little more (or perhaps because he was being paid by the hour), archaic Mark Moseley, the NFL’s last straight-head kicker, finally pushed the football through the Dawg Pound uprights after 77 minutes of play to give the Browns a miraculous win that many of us still hold closer to our hearts than the births of our children.

There’s no need to revisit what happened that following Sunday except to say this: one of the bestselling books currently on amazon.com tells the tale of a four-year-old boy who “died,” got a quick glimpse of heaven, and came back to life to tell the tale.

Old news, shorty. Since January 11, 1987, I’ve been firmly convinced there’s a heaven. And, since you can’t have one without the other, within the hour I also discovered hell.

When Brian Brennan, the Richie Cunningham of NFL wide receivers, reeled in an underthrown Bernie Kosar bomb and sprinted into the end zone for the go-ahead touchdown with 5:43 remaining, the Browns were going to the Super Bowl.

In front of the flickering images of a console television set the size of the Apollo 8 capsule, my dad and I embraced in our living room, neither really believing we were seeing what we were seeing.

Somebody stuck an NBC camera in Brennan’s face on the sideline and, like the good Irish boy he was, he said hello to his mother. He concluded with an exclamatory “Cleveland Browns!” in the tone and cadence of the phrase most of us kept repeating in that moment: “Holy shit!”

Then on the ensuing kickoff, Moseley booted a fluttering knuckleball that bounced and skidded to the Denver 2.

I think a lot of good things have happened to me in my life, and for as screwed up as this sounds, nothing before or since was better. As good, maybe, but never better. For in that four-minute period between Brennan’s catch and the first play of “The Drive,” I experienced absolute nirvana. Complete, unadulterated, “I’ve-got-a-Golden Ticket” happiness.

We had it all. Our dreams had come true.

And then they were ripped away from us.

As we all know, the man who would one day hate Tim Tebow spoiled the party and tied the game with a 98-yard drive, and we found ourselves feeling the way the Jets had going to overtime the week before: like dead men walking.

Finally, in overtime, despite my dad’s desperate prediction that Frank Minnifield was going to break through to block it, Rich Karlis’ 37-yard kick that sailed over the left upright and clearly was no good sent Denver to the Super Bowl.

And so began our acquaintance with the darkness.

Many euphoric and hope-raping moments have followed over the last 25 years, but none represent the opposite ends of the spectrum better than “Jets Double Overtime” and “The Drive”: our V-J Day and our Night of Broken Glass. They are the quintessential bipolar episodes of our lives as Cleveland fans against which all other ups and downs are measured.

As much as I wish the Browns would have gone on to Super Bowl XXI in Pasadena, I know that day - and that week - played a huge role into making me the person I would become: suspicious but appreciative, cautious but hopeful, proud but humble. And maybe just a smidge sadomasochistic.

But there’s no bitterness. For whatever reason, I’m convinced that this is the person I’m supposed to be. And “Jets Double Overtime” and “The Drive” are part of the reason why.

That week symbolizes why we are the way we are. I’m not complaining about it or asking for sympathy or even understanding, just stating a simple fact.

For better and for worse, that week 25 years ago defined us: the good and the bad, the light and the dark, the joy and the sorrow.

The Jets and the Broncos.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)